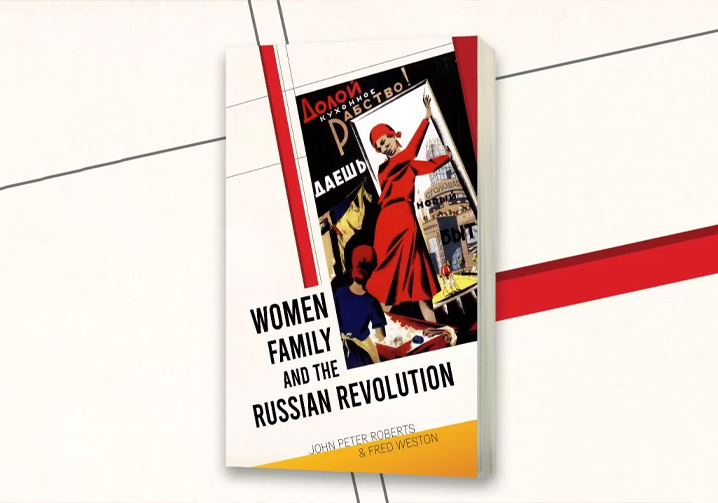

As we celebrate International Working Women’s Day, Wellred Books is publishing a new book, ‘Women, Family and the Russian Revolution’ by John Peter Roberts and Fred Weston. Why publish a Marxist book on women and the Russian Revolution in the year 2023? The answer is that, more than 100 years after the Russian Revolution, we are still very far from achieving genuine equality between men and women. The women’s question has been transformed into one of identity, to be solved within the confines of capitalist society. We maintain that it remains a question closely linked to the class issues we face under capitalism.

[Click here to pre-order your copy]

Marxists were promoting women’s emancipation before bourgeois feminists: they demanded equal pay for women against the opposition of bourgeois feminists; and they called for the right for women to vote without property restrictions way before the suffragettes did. It was the Marxists (Engels and Bebel in particular) who originated the concept of a woman’s double burden – now trumpeted by bourgeois feminists. Marxists also strongly promoted the right of women to equal education opportunities, not least because many leading Marxist women, such as Clara Zetkin, had been denied access to university education.

The Russian Revolution was the first time that Marxists could put into practice their programme and ideas in relation to the problems faced by women. The Bolsheviks proceeded to implement reforms such as full equality in law between men and women. They enormously simplified divorce proceedings, eliminated the concept of ‘illegitimate’ children, granted women the right to an abortion – long before the more advanced capitalist countries, such as Britain or the USA – and decriminalised homosexuality at the same time.

In the 1930s, the Stalinist regime banned abortion, recriminalised homosexuality and rendered divorce more difficult. Despite the counter-revolutionary nature of the bureaucracy, because of the mighty impetus of the October Revolution women in the Soviet Union were, in many ways, better off than many, and possibly most, of their Western counterparts. They had better access to education, equal pay for equal work, much better access to childcare facilities, better maternity/healthcare, the right to their own pension, relatively generous child allowances, were not required to adopt their husband’s name and nationality, had the right to initiate divorce, etc. This confirms that socialist revolution – in spite of the later bureaucratic distortions – gives better results than trying to implement piecemeal reforms under capitalism.

This book outlines the gains of the revolution for women and the partial retreat under Stalinism. But it goes beyond that. It analyses the role of the family after capitalism’s restoration in the USSR. The bureaucracy promoted the family as a conservative basis of support for itself, but the reactionary nature of the family structure fed back into and amplified the greed and self-aggrandisement that was a major motor force driving the Stalinist bureaucracy. Passing one’s privileges on to one’s children became a major factor in the privatisation of Russian state property. And now women in capitalist Russia have lost many of the rights they had won through the 1917 revolution. As capitalism faces its most serious crisis in history, the century of experience since 1917 is full of lessons for today’s struggle for the genuine emancipation of women.