As people around the world watch the war unfold in Ukraine, many are left asking: “What can I do to stop it?” Following in the footsteps of state sanctions, the answer provided by politicians and official organizations has been: exclude Russians from international events, ban Russian products, and boycott Russian businesses. A wave of such actions has swept the globe targeting everything from vodka to cats. Following close behind has been a wave of vandalism, harassment and bullying against average Russians, people of Russian descent, or anyone vaguely associated with Russia. These xenophobic hate crimes are the logical conclusion of the ridiculous boycotts that treat every Russian as an enemy. The working class must stand up against this discrimination.

Silly but symbolic?

After the Russian invasion began, the cultural boycott went into overdrive—starting with Eurovision banning Russians from competing in the international song contest. They were soon followed by FIFA suspending all Russian soccer teams and clubs from competition, as well as the World Curling Federation expelling Russian teams from their championship games. Just before the Paralympic Games were to begin, Russian and Belarusian athletes were sent home.

Now it seems that every organization under the sun is getting in on the action.

In Canada, various provincial liquor control boards pulled Russian vodka off their shelves, despite the fact that the alcohol was already bought and paid for. A performance by Russian piano prodigy Alexander Malofeev was cancelled by the Montreal Symphony Orchestra in a “reaffirmation of solidarity”, even though Malofeev has spoken out against the war and has family in Ukraine.

In the United Kingdom, performances by the Russian State Ballet of Siberia, the Royal Moscow Ballet company and the Bolshoi Ballet were cancelled as a gesture of “solidarity” with Ukraine. The Glasgow Film Festival dropped an entry by Russian filmmaker Kirill Sokolov, despite the fact that he denounced the war and has family in Kyiv.

The boycotts are not limited to living Russian people. Long-dead Russians are being targeted as well. The Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra in Wales pulled Tchaikovsky (who spent much of his time in Ukraine and drew inspiration from Ukrainian folk music) from their program, saying that it would be “inappropriate at this time” to feature the composer. The University of Milano-Bicocca in Milan, Italy cancelled a course on Dostoyevsky, who spent years in Siberian exile for his opposition to tsardom, before reversing the decision due to backlash.

Meanwhile, EA Sports has removed animated Russian teams from their video games. The European Tree of the Year competition and the International Cat Federation have banned Russian trees and cats from competition. And in Quebec, a diner took poutine—the iconic Québécois dish of fries, gravy and cheese curds—off its menu, because it happens to share the French spelling and pronunciation of Vladimir Putin’s name.

CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There is a range of justifications given for boycotts. Some claim that any economic action against Russia, no matter how small, must be taken. Others see the boycotts as part of a collective effort to isolate Russia internationally. Boycotters have cited their need to make a statement of solidarity, sensitivity to the public mood, and concern for their reputation. Many are simply gripped with a sense of urgency. “The Board feels it cannot just witness these atrocities and do nothing,” says the statement of the International Cat Federation.

In fact, such boycotts achieve less than nothing. None of them will significantly affect the Russian economy. The notion that a state that has taken the decision to go to war cares about its inclusion in Eurovision or soccer matches is strikingly unrealistic. As for the claim that boycotts will turn the Russian population against its government, they will actually have the opposite effect, contributing to a siege mentality that pushes average Russians into the arms of the state. Being excluded from a cat competition has never changed anyone’s position on a war.

The only justification that remains is empty virtue-signalling, hollow gestures that only serve to make the boycotters feel better about themselves. But hollow though they may be, boycotts are far from harmless.

The true impact of boycotts

However much organizations, from FIFA to the European Tree of the Year, claim that their actions are aimed at the Russian state rather than Russian people, the fallout from boycotts shows otherwise. After all, boycotts are immediately targeted at Russians who have nothing to do with the war, as if the discrimination they suffer will somehow trickle up to Vladimir Putin himself.

In hockey, for example, the National Hockey League (NHL) cut off business ties with Russia, and shut down access to its digital content and social media in the country. If the NHL is severing ties with Russia, then why not bar Russians from its upcoming draft? The NHL and the Canadian Hockey League are both openly considering this step.

The logical conclusion of this, and of other sporting associations barring Russian teams, is that individual athletes are fair game. An editorial in the Toronto Star said this explicitly when it called for the suspension of individual Russian players from NHL teams. “Too extreme an action for your tastes? The more extreme, the more likely it is to get Mother Russia’s attention,” the editorial says, as if the fate of hockey players means anything in the grand scheme of geopolitics.

The call for expulsions from the NHL has not been taken up, but the message that players are to be treated as the enemy was still communicated loud and clear. In an interview, player agent Dan Milstein described the kind of treatment his clients are facing:

“Clients are being called Nazis. People are wishing that they are dead. These are human beings. These are hockey players. These are guys contributing to our society, paying millions of dollars in taxes to support the U.S. and Canada, and doing all kinds of charity work back home. Stop looking at them as aggressors. Stop being racist.”

He went on to say, “My clients aren’t as nervous for themselves. But when they are on the road, and they have a wife and a newborn child at home that are alone, there are major concerns.” If official organizations are singling out Russian players as legitimate targets for retribution, we can’t be surprised that the general public follows suit.

Russophobic hate crimes

There is a phrase for harassment and death threats based on ethnicity: hate crimes. They are the natural result of the sweeping boycotts of everything Russian.

The mentality created by this general atmosphere of Russophobia was expressed by a resident of Warrington, U.K., one of the many community members outraged that lessons in Russian language, history, and dance were continuing at a local school. They said:

“I am totally disgusted to see that the classes are continuing in spite of what is going on in Ukraine. Putin is putting innocent Ukrainian people through what can only be described as a living hell. Through no fault of their own. I would have thought Warrington Borough Council would have put a stop immediately to these Russian classes and instead should put a united front on. They should not be allowed to continue going on in the face of what is happening to the innocent Ukrainian people. All Russian classes – whether dancing or other academic classes – should be cancelled and not supported.”

These demands are made in the name of “solidarity” with Ukraine, but the content has nothing to do with supporting Ukrainians. Instead they are saying that the mere existence of Russians engaging in cultural pursuits cannot be allowed.

This sentiment is endorsed at the highest levels. In the United States, Member of Congress Eric Swalwell spoke in favour of “kicking every Russian student out of the United States.” In the U.K., Tory MP Roger Gale argued the same thing. Facebook and Instagram have decided to make exceptions to their hate speech policy to allow calls for death to Russians, and to allow praise for the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion.

The material result of all of this is a wave of xenophobic hate crimes that has followed close behind the wave of boycotts.

Russian small businesses have seen a drop in business, accompanied by a rise in online harassment, threatening phone calls, and vandalism. At the Russian Spoon restaurant in Vancouver, the owner has gotten repeated phone calls telling her to shut down, with one person calling to say that “she should die and become worm food.” The owner asked in response, “Why should I die, I just make food?” Describing the angry voicemails he’s received, the owner of Pushkin Restaurant & Bar in San Diego said, “Someone said they would come by and blow up the restaurant and this was gonna be payback for what Russians are doing in Ukraine.” In Washington, D.C., at the Russia House Restaurant and Lounge, vandals smashed windows and broke a door. Taking poutine off the menu in Quebec was presented in the news almost as a joke, but in France the reaction to the food has been more serious. Maison de la Poutine, which serves Québécois food in Paris and Toulouse, has been receiving death threats and insulting phone calls since the invasion.

The fact that the owners of these restaurants have spoken out against the war, or that many of them also sell Ukrainian food or have Ukrainian employees, is immaterial. The simple act of existing while being associated with Russia is the problem. The boycotts that they are experiencing cannot be separated from the xenophobic harassment.

This xenophobia spills over into all areas of life. Russian churches and community centres have been vandalized with paint in Vancouver, Victoria, and Calgary in Canada, as well as in Auckland, New Zealand. In the Czech Republic, one of Prague’s largest real estate developers has said that it will no longer sell or rent properties to Russians. A New Zealand news website has reported on an increase in bullying faced by children with Russian heritage. The Society for Human Resources Management in the U.S. has reported on instances of workplace discrimination and employee harassment, writing in one case, “A manager at an accounting firm put a Russian-speaking certified public accountant on the spot at a team meeting by repeatedly asking her to ‘please explain Putin’s motives for invading Ukraine.’” This harassment lacks even the veneer of being aimed at stopping the war; it is simply Russophobic violence.

The attitude expressed by that manager—that anyone Russian is answerable for the actions of the Russian state—is precisely the attitude encouraged by official boycotts that make every Russian athlete, artist, hobbyist, and business responsible for the war.

Xenophobia is a tool of imperialism

The xenophobia we see today is neither new, nor inevitable. It is a favourite tool of the ruling class, especially in times of war. The more successful they are at pitting workers of different nationalities against one another, the less the capitalists have to worry about workers uniting along class lines. There is no better way of achieving this than to paint other nationalities as some kind of “fifth column” whose very existence presents a threat.

19720121-086

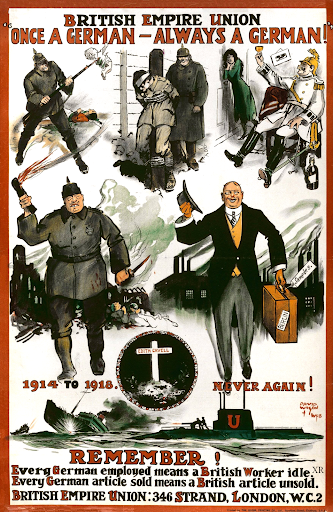

We saw an example of this during World War II, when 120,000 Japanese Americans and 21,000 Japanese Canadians were detained in internment camps until 1949—which itself was the culmination of a period of racist agitation and xenophobic attacks against Japanese people, including having their businesses closed and property confiscated by the state. Similarly, during World War I, Canada interred 9,000 immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire (most of them Ukrainians). At the same time, Britain saw the founding of the Anti-German Union, with slogans like “Every German employed means a British Worker idle. Every German article sold means a British article unsold.”

Encouraging hatred of “enemy” nationals was essential to maintaining public support for the war, at a time when it was important to keep workers mollified. The same pattern is playing out today with regard to Russia.

The boycott and exclusion of Russians is simply discrimination with an official veneer. These kinds of actions are given the approval of the state and other representatives of the ruling class; sometimes directly, such as the vodka boycotts in Canada being endorsed by political parties, and sometimes indirectly, as when news outlets downplay the xenophobia of boycotts in favour of playing up the need to do something. And what are boycotts but the small-scale reflection of Western governments’ economic sanctions against Russia?

The hypocrisy of boycotts has also been ignored. For example, when athletes make statements against racism and police brutality, they are lambasted for “making sports political”. Now, sports are being used to make political statements without hesitation. While the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement against Israel’s oppression of Palestine is denounced, senseless boycotts directed at Russia are now embraced. The discrepancy here is deliberate. Russophobic actions serve the interests of Western imperialism, whereas action against racism and oppression does not.

Need for solidarity

Boycotts and discrimination will not help to end the war. Far from turning Russians against their government, these measures tell Russians that the whole world is against them, allowing Putin to present himself as their sole defender. By hardening national divisions, they help cement support for the war. This suits Western imperialists very well, as they would prefer to exhaust Russia militarily than see a quick end to the conflict.

What are workers in the West to do instead?

A recent Guardian article interviewed a priest who threw red paint over the gates of the Russian embassy in Dublin. Explaining his actions, he said, “I feel frightened and powerless. The only thing I could do was, in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, to pour paint on the gates on the building that is spreading lies and deceit and misinformation about what is happening.” This kind of individual hopelessness is very telling. It underlies much of the anti-Russian hysteria. And it is exactly how the ruling class wants us to feel.

As individuals, we are helpless. It is only when workers unite as a class that they are powerful. It is, after all, the working class that makes the world run—and that can bring it to a stop with collective action. It was revolution in Germany that ended World War I; and it was organized resistance in the U.S. Army and unrest at home that finally brought an end to the Vietnam War. Workers end war with solidarity.

The Russian people are not our enemy. The Russians getting arrested for protesting the war are the only ones who can hope to have an impact on Putin’s regime. Boycotts and sanctions only hurt them. We can support their efforts and show solidarity by opposing our imperialists here in the West; by opposing sanctions, boycotts, discrimination, and anything that sets the working class of different nations against each other.

The enemy is at home, not in the form of a fifth column of Russian workers, but in the form of our own ruling class.