On 25 February 1986, the infamously corrupt and brutal dictator of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, fled the country with his family from a revolutionary mass revolt. Yet on 9 May 2022, another Ferdinand Marcos was voted in as president: the son of the senior Marcos also known as “Bongbong.”

A chorus of liberal lamentation erupted on cue. There was an outpouring of fear and loathing for the supposed return of the dictatorship, and cries of anguish at the supposed stupidity of the Filipino voters, which flooded the pages of Filipino and International media. But what is the real perspective in the situation? Is the Filipino Rebolusyon dead and buried, or is it still impending?

Tables have turned

Bongbong Marcos’ father was internationally recognised as a brutal right-wing dictator and likely the second-most-corrupt head of government in human history, going by the wealth he embezzled. His overthrow by the masses in what was known as the 1986 “EDSA revolution” (also known as the “People Power revolution”) marked a turning point in the Philippines’ history. The bourgeois liberals who stepped into power after Marcos’ fall promised to build a thriving democracy, one that would never again produce another regime like that of Marcos.

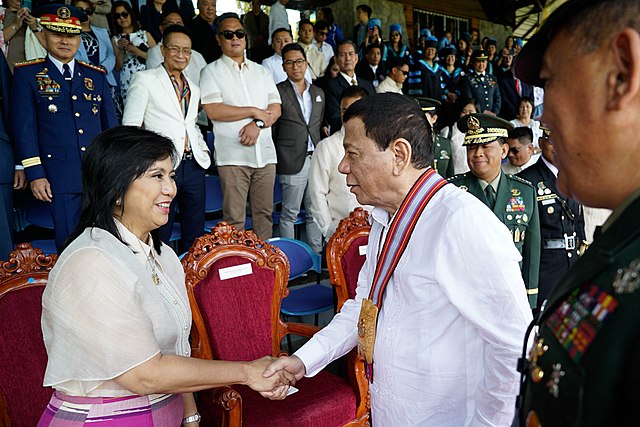

Source: Bluemask, Wikimedia Commons

Yet this year, not only was Bongbong Marcos allowed to run on a platform of nostalgia for his father’s time in office, the junior Marcos enjoyed a commanding lead in the polls throughout the election campaign. He gained overwhelming support from the youth, with 71 percent of voters between age 18 to 24 supporting him. Bongbong’s main opponent, Maria “Leni” Robredo, on the other hand, consistently trailed behind him by at least 30 percent in the polls. Long before election day, a new Marcos presidency was a foregone conclusion.

In the end, Bongbong obtained over 58 percent of the vote share, and received more than double the votes cast for Leni Robredo. Bongbong’s vice-presidential running mate, Sara Duterte-Carpio, who is current president Rodrigo Duterte’s daughter, similarly trounced her opponents, with 61 percent of the vote.

What explains this crushing triumph of Bongbong over the very same system that was supposedly designed to prevent the emergence of another Marcos? To answer this question, we must look at the conditions in the country that gave rise to Duterte’s presidency.

The ‘Duterte Factor’

In actuality, Bongbong Marcos’ successful presidential run is nothing but a rehash of the very same conditions that the current president Rodrigo Duterte took advantage of: the collapse of the masses’ trust in the ‘liberal’ political establishment that emerged after the EDSA revolution. The post-EDSA era was an abortion of a bourgeois democracy, with regional and political dynasties taking turn in plundering the country, while the masses faced an endless cycle of poverty, toil, disease, natural disasters, and crime.

The Congress of the Philippines is a naked thieves’ kitchen from the point of view of the masses. The politicians’ surnames usually carry more weight than the party or programme that they represent. These self-interested crooks frequently change parties, or form new ones, and votes are mobilised by the loyalty networks of each candidate, often through vote-buying.

Vote-buying is so rampant that even the ‘respectable’ Leni Robredo advised voters that they might as well accept the bribery but still “vote their conscience.” Research conducted by the Institute of Philippine Culture showed that the poor often consider selling their votes to be a logical decision. How could it be otherwise when they live in a country with one of the lowest average wages in the world?

There is, of course, no political representation for the working class whatsoever, and thus establishment politics has no authority or meaning for the general masses, who continuously toil in absolutely horrible conditions irrespective of who leads. This is the context we need to keep in mind when deciphering the results of any election in the Philippines.

In 2016, a candidate emerged that finally found a degree of connection to the Filipino masses: Rodrigo Duterte. This scion of a Mindanao regional dynasty used brash language, tirades against “crime and drugs”, as well as occasional demagogy about being a socialist to drive a meteoric rise in the polls, eventually seizing the presidency. In the face of a deeply discredited ‘liberal’ establishment, characterised by domination of corrupt ‘fat’ dynasties, who are the stooges of US imperialism, Duterte filled a political vacuum.

While Duterte’s posturing about being “tough on crime” and brash style horrified international bourgeois spectators, his brutal use of state violence was business as usual for the Filipino bourgeoisie. It is true that Duterte launched a campaign of extrajudicial killings that resulted in upwards of 12,000 deaths. He also used a phony reignition of war against the guerilla forces of the Communist Party of the Philippines – New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) – as means to suppress his detractors among the masses and within the ruling class. But measures like these are not out of the ordinary for bourgeois politicians of all shades. According to Inday Varona, all previous administrations have used “red-tagging” or accusing someone of being linked to the CPP, to repress journalists such as herself.

Both the Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo administrations used the pretext of “all-out-war” against either the CPP-NPA or the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) to repress critics. Arroyo’s administration was particularly murderous, with National Union of Journalists of the Philippines reporting that her administration is responsible for almost twice as many extrajudicial killings of journalists as under the Marcos dictatorship. The ‘liberal’ Noynoy Aquino administration did very little to change the rampant violence, repression and abuse of democratic rights that have blighted the country.

Duterte is only different in style and scale than other administrations, the brutality is fundamentally nothing new. The Filipino state was already bloodthirsty and repressive. Duterte, whatever his personal ambitions might have been, did not wield a level of power that was qualitatively different from all the presidents after the EDSA revolution, and he certainly wasn’t a bonapartist dictator.

He was, however, the favored candidate of a wing of the Filipino bourgeoisie who sought to preserve their interests by pivoting away from the US and towards China. His mandate strengthened the agenda of that particular wing of the capitalist class, at the expense of those who are still tied with a thousand and one threads to Uncle Sam. The Marcoses are also part of the pro-China wing, and were in close touch with the Chinese Embassy even before Bongbong officially launched his presidential bid.

After the Philippines has seen so many governments that failed to make even an iota of change in the situation, the agenda that Duterte represented for a time seemed to produce some results. A rapprochement to China as well as enlarged deficit spending coincided with a slightly higher level of economic growth than in the past. The level of unemployment rate went from 6 percent in 2015 to 4 percent by 2020. Universal health insurance coverage was established. These results, backed by Duterte’s assertive demagogy over the war on drugs and communists, produced certain illusions that he is a wise steward for the country.

Duterte did attempt to amend the constitution to allow for a second term in office, but failed to do so ahead of this election. He thus yielded to a compromise in effectively supporting the next candidate from the camp he is aligned with: Bongbong, while consenting to having his daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio run as the vice presidential running mate of Marcos. The fact that Bongbong clearly styles himself as a torch bearer of Duterte’s policies, with the latter’s blessing, is the main source of his base of support, both among the masses and a section of the ruling class.

Status quo in ruins

But this popularity could not have been achieved without the utter impotence of Bongbong’s opponent, Leni Robredo, erstwhile victor over Bongbong in the previous vice-presidential election. Robredo represents nothing but the pro-US wing of the Filipino bourgeoisie. Robredo herself has nothing to offer to the masses and never has.

She claims to champion a socially progressive agenda that will be beneficial to women, but the Liberal Party establishment from which she hails has done nothing to put forward this agenda, despite having been effectively in power for decades since the fall of the senior Marcos. She claims to want to root out the domination of dynasties in Filipino politics, but she herself only stepped into the limelight as the widow of Jesse Robredo, former Justice Minister with a clientele base in Naga, Camarines Sur. Her daughter Aika is also expected to step into politics.

Leni Robredo’s ‘progressivism’ also rings hollow given that she is clearly the favoured candidate of the Catholic Church in the Philippines, whose reactionary intervention into social policies in the country, especially its staunch opposition to contraception, earned it justified resentment from the youth. Western and liberal media in the Philippines moved might and main to portray Leni as a ‘progressive’ but the hypocrisy is only too apparent to the voters, who are particularly youthful in the country, with 52 percent of total voters aged between 18 and 40.

This election is thus a contest between two candidates that both represent the hypocritical, corrupt, and discredited Filipino establishment. One has styled himself as the continuity candidate of Duterte’s demagogic Keynesiansm, while the other lays claim to discredited liberalism. It is already understood by most of the masses that, no matter who wins, they won’t actually be represented, so they might as well endorse the candidate whose predecessor yielded some small improvements.

This is the real reason for the Bongbong’s success in these elections, not a “lack of education about the martial law era” or “culture of popularity contest”, as the clueless liberals would have us believe. If there are some illusions in Bongbong, the school of a second Marcos administration could very well lead the Filipino masses to the same conclusions that pulled down Marcos Sr.

Will Bongbong be another dictator?

Naturally, there is a tendency to ask whether another Marcos dictatorship will emerge in the Philippines. In a country where the state (police system and military) already holds outsized power over the masses, the emergence of a new dictator in Malacañang Palace is a perspective that is worth carefully interrogating.

The landslide victory of Bongbong this year was a result of the deep discontent within the masses, who found no class expression due to the lack of a mass workers’ party with a revolutionary socialist programme. We have seen these conditions in many places in the world.

Whatever Bongbong’s ambitions are, he faces an undefeated working class that is yet to be tested in the field of open class struggle. Many among the masses may have some illusions in Bongbong for now, but as soon as he begins to attack their interests, he will have to reckon with a titanic struggle from below, like those we’ve seen all over the world and throughout the Philippines’ own history.

The Marcos-era totalitarian dictatorship following the declaration of martial law of 1972 emerged in very different conditions. For an in-depth analysis of these events, we refer readers to this 1987 document authored by our tendency. But the process of his rise to power can be summed up thusly: prior to the declaration of martial law, Filippino capitalism was in a state of collapse, while the radicalization of the masses resulted in huge protests and the swelling of the CPP-NPA guerillas into a force of tens of thousands.

The pressure in society at the time was so large that it even resulted in a fracturing within the bourgeoisie and the state. And yet there was no revolutionary leadership present capable of directing the masses towards the overthrow of capitalism. The prolonged stalemate eventually exhausted the masses, while some manoeuvring on Marcos’ Sr’s part eventually allowed him to rally the Filipino bourgeoisie and US imperialism behind him as the butcher-in-chief at the head of the counter-revolution.

Today, from the standpoint of the bourgeoisie as a class, there is at this time no need to change the totally rigged system that they’ve built among themselves, which allows them to take turns in plundering the masses. A dictatorship like that of Marcos Sr. is not something that any of them is interested in for the moment. Only when they begin to feel sufficient existential threat from the masses would they feel a need to give power to an individual to impose bourgeois rule by the sword.

The prospect of a bonapartist Bongbong regime is thus ruled out in the near term. But even without such a phenomenon, the level of daily oppression experienced by the people, both directly via the state but also the decrepit living situation in the country, is already doubtlessly barbaric. A bourgeois dictatorship already exists in the Philippines, under a paper-thin veneer of “democracy”. Widespread poverty already forces the majority of the society into a ceaseless and humiliating fight for survival.

Looking ahead

Despite his success at the polls, Bongbong’s regime will not be based on firm foundations. On the contrary, Malacañang is transforming into a house of cards.

Bongbong, carrying Duterte’ torch, will inevitably have to carry on a regime of deficit spending to finance some superficial reforms and concessions. The general trajectory of pivoting away from the US towards China will likely continue. At the present stage, China simply offers a better deal than the West does, one that allows for the Filipino national bourgeoisie to maintain more autonomy for their own sake.

But whenever they sense that the US can once again make a better offer, then they will not hesitate to make a rapprochement, just as Duterte did when he suddenly cancelled his plan to forbid American troops from being stationed in the country, in exchange for the US’s helping hand in fighting insurgents.

The upcoming Marcos’ administration will continue this balancing act between different imperialists to justify itself to the masses. Bongbong will want to show he is not beholden to any imperialists and can play the big powers off of each other for the benefit of the Filipino people. This is the very same game that the ruling class in countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan and others tried to play. But the result is not going to be a more independent country that gets the best of both worlds, but a country that is indebted on all sides, while the masses are made by their ruling class to foot all of the bills. This is the fate of all dependent and exploited countries in a period of world capitalist crisis.

The same scenario will unfold in the Philippines. The debt-to-GDP ratio, which had been climbing steadily, has risen dramatically in recent years. Between 2021 and 2022 alone, the debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 54 percent to 60 percent. Government borrowing and interest payments both reached record highs.

Duterte’s deep dependence on foreign investment set a precedent, and provided an impetus for future Filipino governments to repeat the same measures that paved the way to the crisis in Sri Lanka today. How quickly the contradictions will express themselves in the Philippines remains to be seen, but it is highly likely that it could happen under Bongbong, during his five-year term in office.

If this does happen, splits could emerge within the ruling class, along with mass movements from below, just as under the senior Marcos. What is ruled out is an intervention by the helping hand of US imperialism, which is relatively weakened. Meanwhile, China is not strong enough to prop-up the regime single-handedly.

The Philippines is also not immune to the instability affecting other ASEAN countries, above all Myanmar, but also countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia. A superabundance of inflammable material (to use Lenin’s phrase) already exists in the Philippines thanks to the crisis of capitalism in general. Mass struggles in neighbouring countries could very well inspire the Filipino masses to follow suit.

The perspective, then, is one of protracted crises and sharp and sudden changes. In this process, conditions for Filipino masses will continually decline, fuelling an accompanying rise in the class struggle sooner or later. These will surely supersede the scale of the EDSA that toppled Marcos Sr.

The youth will play a particularly key role in this process. Despite their apparent enthusiasm for Marcos, 92 percent of young Filipinos indicate that they are still frightened about their future. Indeed, capitalism does not offer them any future.

Filipino workers and youth have experienced the bitter failures of liberal bourgeoisie, as well as the bankruptcy of CPP, its class-collaborationist leader Jose Maria Sison, and Stalinism in general. The immediate task of left-wing workers and youth in the Philippines is winning a party of their own, with a revolutionary programme.

This would provide a means to sweep away all the conniving bourgeois crooks and fight for the interests of working people and the poor. The ultimate objective must be the establishment of a workers’ government, which will facilitate the democratic planning of the economy for the good of all. This would be a tremendous impetus to revolution throughout Asia and the world. The rebolusyon depends on it.

We call on progressive Filipino workers and youth: if you agree with our analysis, or seek to clarify your views in comradely debate, please contact us, or consider attending our upcoming, online International Marxist University. We invite you to join us in the fight to build the forces of Marxism in the Philippines, and for socialist revolution!