It has been 50 years since the coup d’état against president Allende in Chile. In this article, Carlos Cerpa Mallat describes the events that preceded the coup, how the transition from dictatorship to the current regime took place, and draws the main political conclusions of that tragedy, which are necessary to arm the new generations.

On 11 September 1973, the coup d’état took place against the government of the Socialist Party President of Chile, Salvador Allende. It was the first time that a candidate identified as a Marxist had come to power by electoral means, which generated great illusions in social democracy throughout the world. But the counterrevolution was implacable. For US President Richard Nixon, toppling Allende was a matter of “making the Chilean economy scream.” Imperialism intervened through the CIA, dedicating more than 13 million dollars to right-wing parties, media and bosses associations, which for three years would commit economic sabotage, reactionary communication campaigns, and terrorism.

On the other hand, the working class put the forces of reaction in check on several occasions in a formidable display of mobilisation and conscious organisation in defence of its class interests against the right wing and imperialism. Organised in the Cordones Industriales, the Juntas de Abastecimiento y Precio, and other groupings, the Chilean workers left for us a valuable experience of self-organisation, which showed in an embryonic way how it is possible to direct production and manage society on a new basis. But their impulse towards the seizure of power was curtailed on every important occasion by the communist leaders and the socialist president himself, who called on the masses to trust the Armed Forces, who would be their executioners.

The dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet left behind thousands of murdered and missing detainees, in addition to inflicting unspeakable tortures. In a small country of 10 million inhabitants, official figures indicate that at least 40,000 people suffered human rights violations, mostly young people, workers and peasants. The flower of the Chilean youth and working class was annihilated. The experience of the Allende government shows that the institutional road to socialism is not possible. It represents the failure of reformism, which does not understand the class character of the state.

Popular Unity

In 1969, the Popular Unity (UP) was formed, composed mainly of the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, and petty bourgeois parties such as the Radical Party. It was a popular front, with the particularity of being led by two mass workers’ parties.

The Popular Fronts were a policy of the Stalinist Comintern, which called on the Communist parties to form alliances with parties of the supposedly ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie. But at bottom, the popular fronts meant the subordination of the working class to the interests of the bourgeoisie, under the veil of an anti-fascist alliance. The Popular Unity succeeded in mobilising very broad sectors of the working masses: a culminating moment of a decades-long process of mass radicalisation in Chile and on the continent.

The Christian Democracy was formed as a party that sought above all to stop the growth of the workers’ parties. In 1964, the Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Montalva, campaigning with leftist phraseology and under the slogan of “Revolution in Liberty,” defeated Salvador Allende in the presidential elections. Agrarian reform was initiated, which fulfilled only one third of the plan to benefit 100,000 peasant families; as well as the “Chileanization” of the copper sector, which established mixed companies with 51 percent state participation in mining. But the limits of these reforms only fueled the desire for profound transformation.

The strength of the working class already stands out at that time. In 1970, 85 percent of the population were wage earners, 46 percent of whom were labourers. The Central Unitaria de Trabajadores (CUT), the main union federation, organised 700,000 members, and during the socialist government it reached one million members, a third of the active population. In the public sector, unionisation reached 90 percent. In 1965, there were 723 strikes, and in 1972 they reached 3,526, of which only 3.4 percent were considered legal. But at the same time, the situation facing the working class was precarious. Almost half of the working population earned less than the minimum wage. In 1970, a quarter of the national population did not have their own family housing, and in Santiago 10 percent lived in shantytowns.

In 1965, the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) was founded, the result of the merging of various groups. Among them was the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (Revolutionary Workers’ Party), with origins in the Chilean Left Opposition of the 1930s. But the MIR was dominated by petty-bourgeois and academic elements, who promoted peasant guerrilla warfare. In 1969, they bureaucratically expelled those who opposed it, mainly working-class cadres. During the Allende government, the MIR was the most important revolutionary left group with some mass support. From 2,000 members at the end of the 1960s, it reached 6,000 in 1973, and was able to mobilise some 15,000 people, including sympathisers. The peasant wing of the MIR, the Revolutionary Peasant Movement, surpassed the legality of the agrarian reform process. Very significantly, in La Araucanía region, mobilised together with the Mapuche, they achieved the expropriation of almost 200,000 hectares of private land, which were returned to indigenous communities.

In 1970, the Communist Party had 60,000 members, one of the largest in Latin America and the largest in the Popular Unity. The Communist Youth reached 80,000 members in 1973. The Socialist Party was further to the left than the Communists, and had an explosive growth during the three years of the Allende government, going from around 55,000 members to 125,000 members in 1973. Thus, as a whole, the leftist parties had between 200-300,000 members. For its part, the Christian Democrats had some 60,000 members, with an important presence in trade unions, while the right-wing opposition and fascist groups had around 30,000 members.

For his part, Salvador Allende was a doctor who, over the course of his career was a parliamentarian, minister of health, and four-time candidate for the presidency. He finally won the elections on 4 September 1970, with 37 percent of the vote. Right-winger Jorge Alessandri obtained 35 percent and the Christian Democrat candidate 28 percent. The division of the right-wing and Christian Democracy votes allowed the Popular Unity to obtain a majority. But this triumph is also an expression of the rise of the masses during the 1960s.

Since he did not obtain an absolute majority, Allende needed congressional ratification to assume the presidency. The US and CIA conspiracy began before he assumed office. A false flag kidnapping was prepared against Commander-in-Chief Rene Schneider, led by General Viaux, with the participation of the fascist group Patria y Libertad (Fatherland and Freedom). The plan was to blame the revolutionary left for the kidnapping and provoke a military putsch that would prevent the congress from ratifying Allende. But the plan did not work: Schneider resisted the kidnapping with his gun, and the far-right gunmen had to liquidate him. The coup plot was revealed, which forced the supposedly democratic institutions to support the peaceful transfer of power.

The position of commander-in-chief was passed by seniority to Carlos Prats, another military officer considered a ‘constitutionalist’, like Schneider. In any case, instead of holding out hope for ‘constitutionalists’ within the state apparatus, the Popular Unity parties should have taken heed of the obvious danger of a military uprising that would force an armed confrontation between the workers and the counterrevolution.

Ultimately, Allende was ratified under the condition of signing a Statute of Constitutional Guarantees, which established the autonomy of the Armed Forces. That is to say, from the very first moment, the hands of the popular government were tied over the fundamental question of the character of the bourgeois state and its armed wing.

The Popular Unity programme

The Popular Unity in government applied its programme of democratic and anti-imperialist reforms, including measures in favour of workers unprecedented in the history of Chile: nationalisation of natural resources being the most emblematic; along with the nationalisation of copper (considered the “salary of Chile”); partial nationalisation of banking, foreign trade, and strategic companies, such as the ITT telephone company; acceleration of the agrarian reform initiated by the Christian Democrat government; social reforms called the “40 measures,” such as the delivery of half a litre of milk daily for all children; and the freezing of rent.

The strategy of the Popular Unity proposed a gradual transition to socialism through institutional channels. It argued the specificity of the Chilean State as a stable political system and considered the Armed Forces as “constitutionalist” and respectful of democracy. In addition, it defined the existence of a progressive national bourgeoisie.

The Social Property Area was created, with workers’ participation, comprising 90 nationalised strategic companies. The workers would take this initiative further through occupations. As many as 254 monopolist companies were included in the Social Area.

During the Popular Unity government, there were more than 2,000 land occupations. While the Christian Democrat government had expropriated 3.5 million hectares of land, Allende’s agrarian reform expropriated 5.3 million hectares of basic irrigated land, reaching up to 35 percent of agricultural land.

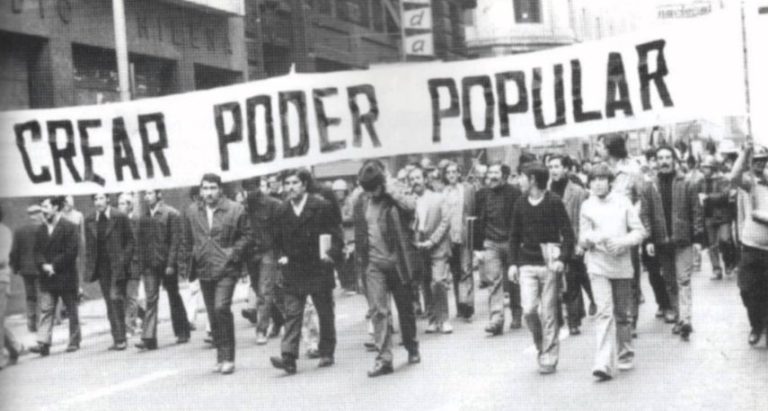

The self-organisation of the workers in the Cordones Industriales (Industrial Belts) is the highest point of this Chilean revolution; a revolution “from below,” which surpassed the revolution “from above” of the Popular Unity government programme. As the slogans of the time said, it was a dispute between “advancing without compromising”, and “consolidating in order to advance.”

In 1973, the Social Area of nationalised companies came to comprise 30 percent of the industrial workforce and 90 percent of mining production. During the first year, there was an industrial growth of 12 percent. In fact, until mid-1972 there was a small golden era. In some nationalised textile companies, production doubled. The consumption of national products doubled, a sign of a better quality of life for workers, who could now buy household appliances such as washing machines and refrigerators, and who consumed more meat and milk. However, the state only controlled 15 percent of distribution. This would be taken advantage of by the bourgeoisie, which used the control it maintained over the economy to sabotage the government. At the same time, the imperialist boycott blocked access to spare parts and machinery.

According to the project of the Popular Unity, the key was the rapid implementation of a planned economy in the Social Area, which would transform the relations of production and increase productivity. However, the Allende government’s nationalisation measures, which did not replace the anarchy of the market with democratic planning, provoked the sabotage of the bourgeoisie. This contributed decisively to the deterioration of the social and economic situation, leading to defeat.

Despite the difficulties, electoral support for the government increased; the Popular Unity parties obtained 50 percent in the 1971 municipal elections. The Socialist Party grew from 12 percent to 22 percent.

In 1971, a sector of the Christian Democracy that supported the Popular Unity resigned, following the example of the MAPU, which split from the Christian Democrats in 1969. This positive development showed the adhesion of some middle sectors to working-class interests, but on the other hand the Christian Democracy remained under the control of its right wing.

Industrial Belts

The ruling class abandoned its hopes of overthrowing the government by democratic means, and in October 1972, a strong bosses’ offensive was launched with the aim of overthrowing the government. The bourgeoisie and imperialism were aware of the sharpening of the class struggle under the Allende government, with the working class threatening to surpass the limits of bourgeois democracy. They were not willing to lose their power, wealth and privileges without putting up a fight. Unfortunately, the leaders of the left did not have the same clarity of vision and continued to rely on the supposedly democratic character of the Armed Forces, and the possibility of advancing to socialism gradually without breaking with bourgeois democracy.

Industrialists froze their activities. The truck drivers’ union carried out a reactionary stoppage that affected the transportation of fuel, raw materials, food, and maritime cargo. Students from the Catholic University, doctors, engineers, and public transportation joined the strike. The opposition managed to drag along the middle classes.

The workers responded by occupying the factories abandoned by the bosses and the Cordones Industriales flourished, as democratic, rank-and-file workers’ organisations. They controlled production, and made their own spare parts, which were scarce due to the economic blockade. To organise the distribution of basic products, the Juntas de Abastecimiento y Precio (Supply and Price Committees) multiplied, which fought hoarding and the black market. As happens in all revolutions, an embryo of dual power was established, which went beyond the factories, and could organise peasants and the poor. Between 20-30,000 workers mobilised in Santiago around the Cordones Industriales.

After a month, the bosses’ strike was defeated, and Allende formed a civilian-military Cabinet. This was a slap in the face, since the military was called upon to mediate in a conflict where the working class had already triumphed. He placed the military together with union representatives in his cabinet, confusing the independent workers’ organisations with the government.

In an attempt to avoid an inevitable confrontation, in January 1973, the government presented the Prats-Millas Plan: to return the factories occupied in October, which were not in the government programme. It also reduced the Social Area plan from 90 to 49 enterprises. This was unacceptable to the workers, who resisted the measure, and the plan was withdrawn in February 1973.

A Gun Control Law was also enacted, which was used in raids against the Cordones Industriales. Meanwhile, in the months before the coup, fascists carried out at least 20 attacks daily. On the basis of blind confidence in the democratic character of the state, the workers were disarmed, while the fascist gangs ran wild.

In the parliamentary elections of March 1973, Popular Unity obtained 44 percent. The right wing did not succeed in decisively weakening the government in the electoral field. For all advanced workers, the coup conspiracy was evident, and the coup itself imminent. The question then was whether to wait for the aggression or to take the initiative. The art of revolutionary insurrection requires means of defence, timing and coordination. But the bulk of the preparatory work should be devoted towards creating a political task directed at the soldiers with a general programme of democratisation of the armed forces, with the aim of organising anti-coup units.

On 29 June 1973, a sector of the army revolted; the so-called Tanquetazo, organised by middle-rank officers linked to Patria y Libertad. Commander-in-Chief Prats, accompanied by a certain General Augusto Pinochet, repressed the rebels in downtown Santiago.

General Prats then reflects in his diary:

“There is no longer any doubt in my mind that a considerable number of general officers of the armed forces and carabineros maintain political ties with opposition leaders, and that these contacts are conspiratorial in nature. (…) Why not talk politics in the barracks, if a regiment with its commander at its head has taken to the streets to attack the presidential palace and the Ministry of Defense, and if the commander in chief has also had to take to the streets to defend the constitutional government with a machine gun in his hand?”

The Cordones took the initiative and occupied all the factories in the capital, seized the main access routes to Santiago, and the peasants’ centralised the food supply. The putsch was defeated. But serious flaws were evident; groups of workers wandered without direction through the streets of Santiago. At the end of the day, Allende asked, once again, that the companies occupied during the day be returned and that workers go back to their homes in peace.

Since Prats and Pinochet repressed the uprising, the Communist Party believed that its thesis that the Armed Forces were constitutionalists was confirmed. In reality, the Tanquetazo was only a dress rehearsal, which proved that the conspiracy was at full speed and it was only a matter of time before another coup was sprung.

This was still a favourable moment for the government to rely on the working class and launch an offensive that would definitively expropriate the bourgeois saboteurs. The contradiction was between defending a government that the workers considered their own, and the need to overcome it by revolutionary means. This same government disarmed them politically and materially in the face of the counterrevolution. The socialist revolution was the only means of defence.

The coup-plotting officers of the Navy understood that the Navy and the Air Force would not be enough to lead a successful action against the government. It was essential to count on the support of the Army, and in this, General Carlos Prats was an obstacle.

General Prats was harassed by the press and by protests from the military wives; he faltered under the psychological pressure, and then Pinochet assumed the position of command in chief. Prats described him as follows:

“He is the scoundrel of limited lights and excessive ambition, capable of spending a lifetime crawling or crouching down waiting for the moment to commit a crime by force, which will allow him to change his destiny by a bold stroke of daring. I am convinced that he only jumped on the bandwagon of the coup plotters at the last minute, but I have no doubt that he will cling to power whatever the cost. He will remain as the great traitor of our history. The one who led the army and the armed forces to commit a major and irreparable mistake.”

The Army command had thus taken its place in the coup plot. Prats would be assassinated months later in exile in Buenos Aires.

Constitutionalist sailors and the coup

It was known that the main conspirators were in the Navy and that they met regularly with US military advisors. Under the guise of making preparations for the UNITAS operation, they actually prepared communication codes between US and Chilean ships for the coup d’état. In addition, the navy provided weapons and military training to Patria y Libertad, while the officers shouted openly pro-coup slogans to the troops.

A group of sailors knew of the plans of their officers to overthrow the government. They also knew that there were many sailors opposed to a coup. Two strategies were developed that divided the opinions of the group. One idea, inspired by the 1931 uprising of the navy when the sailors imprisoned the officers and took control of the ships, was to react only in case of a coup, where they would occupy the ships and take them to the high seas, out of use for the counterrevolution.

The other idea was to anticipate the coup, with part of this group deciding to contact political leaders of the revolutionary left. The MIR, the MAPU and the Socialist Party did not agree with the plan in its totality as presented by the group, nor did they reach consensus among themselves. The lack of unity of a revolutionary leadership of the workers was another disadvantage, while the counterrevolution was able to solve this problem through the three hard years of opposition, obtaining unity of command for the coup.

In August 1973 the meetings with the left were discovered. The sailors were prosecuted by the military justice system, accused of insurrection and tortured. Scandalously, Allende does not intervene to help them, arguing that to do so would violate the autonomy of the Armed Forces! This was decisive for the eventual defeat, since it discouraged the rank and file soldiers and sailors from acting in defence of the government. In addition, the Popular Unity did not elaborate a policy for the armed forces, and the troops were not listened to.

One of the tortured sailors, a corporal, would say years later: “I think Allende was more concerned about winning the command, about winning the officers (…) So he neglected us NCOs.”

On 4 September, 800,000 workers marched in front of the house of government, La Moneda, demanding weapons and the closing of congress. On 5 September, the Cordones Industriales sent a letter to President Salvador Allende, highlighting some of the workers’ demands:

“…We consider not only that we are being led to the road that will lead us to fascism at a dizzying pace, but that we have been deprived of the means to defend ourselves.

“Therefore we demand of you, comrade President, that you place yourself at the head of this true army without arms, but powerful in consciousness… that the proletarian parties put aside their divergences and become the true vanguard of this organised but directionless mass.

“We demand:

(…)

“With regard to the social area: not only should no company be returned where there is a majority will of the workers to be intervened, but it should become the predominant area of the economy.

(…)

“We demand the repeal of the Gun Control Law… that has only served to harass the workers, with the raids practised in industries and towns, which is serving as a dress rehearsal for the seditious sectors of the armed forces, who thus study the organisation and response capacity of the working class in an attempt to intimidate them and identify their leaders.

“In the face of the inhuman repression of the sailors of Valparaíso and Talcahuano, we demand the immediate freedom of these heroic class brothers, whose names are already engraved in the pages of Chilean history.”

However, Allende and the Popular Unity leaders remained stubbornly attached to their conception of a ‘democratic’ state that obeyed the government, and a ‘constitutionalist’ armed forces that respected the chain of command. That path led directly to disaster, as the Cordones Industriales warned in their letter:

“We are absolutely convinced that historically, reformism sought through dialogue with those who have betrayed time and again, is the fastest road to fascism.”

Ignoring the clamour of the working class, Allende proposed a plebiscite to the parties, in an attempt to use parliamentary methods to resolve the conflict of powers between the government and the opposition in Congress. The date of the coup was then set for 11 September, to prevent the announcement of this measure.

Every uprising needs a moment of “overflow”, a delicate moment in which the forces jump from stasis resolutely into offensive action. The surprise factor relies on secrecy and deception. That there was a coup in the making was no secret, but the leadership of the left, mainly the communists and Allende himself, were deceived by their own political theses on the constitutionalism of the armed forces.

The General Staff had elaborated an anti-insurrectional plan in case of emergencies to defend the government (the ‘Hercules Plan’), but in reality this was applied to the overthrow of the government itself. As it was already public knowledge that the Navy were coup plotters, the coup began at dawn in the port city of Valparaiso. Then the natural response would be to send the regiments from Santiago to suppress the uprising. In reality, they would only go to a friendly meeting with the rebels, to neutralise any resistance and proceed with the coup in Santiago.

Joan Garces, close advisor to President Allende explains:

“Pinochet’s work consisted in converting the device destined to defend the government into a centre of direction and support for the insurrection (…) But the success of Pinochet’s action cannot be explained without considering the decisive fact: in front of the state apparatus there was no organisation with the capacity for military resistance (…) The absence of any autonomous proletarian coercive capacity left the Popular Unity with no other military choice but to continue supporting the officers who appeared to have a professional and democratic conscience”. (Allende y la experiencia chilena. Joan Garces. 1976. p.363).

The workers, deprived of political leadership, concentrated in the workplaces, awaiting instructions. Faced with an enemy superior in arms and organisation, what was called for was to respond with mobility and communication, not to remain in fixed points. Some factories and working-class neighbourhoods resisted heroically, but the military gained control of the whole situation in a few hours.

It is said that Allende did not arm the workers. That is true, but it is not the best way to pose the problem. The problem is that the main organisations toyed with the military question without seriously considering it. It was necessary to form cadres, to develop a policy directed to the rank-and-file soldiers, and eventually to prepare a force of their own. It is not enough to suppose the existence of sympathetic sectors in the armed forces: the active coefficient of the class struggle is needed. A decisive action of the organised masses could have won over a sector of soldiers and sailors, breaking the Armed Forces along class lines. Above all, a revolutionary party was needed to direct the tremendous creativity and combat-readiness of the working class and its vanguard. Sadly, in the absence of this, the masses were politically disarmed.

The dictatorship

Frei Montalva and the Christian Democrats thought that the military would hand over power to them in the short term. But the dictatorship dragged on for 17 years. The masses were demoralised and powerless in the face of the triumphant reaction. There was a disastrous economic situation, after years of sabotage by the right wing itself, but also as a result of the international capitalist crisis. Despite its internal contradictions, the dictatorship was able to maintain itself by inertia.

In the leftist organisations in hiding and in exile, strong internal debates began. It was a question of defining three things: the causes of the defeat of the Popular Unity government, the character of the military dictatorship, and finally, by what means to put an end to the dictatorship.

The Chilean working class had defeated the counterrevolutionary offensive on several occasions, notably in October 1972, and showed its potential to lead the economy and society. It was necessary to generalise these experiences and coordinate them at regional and national levels. Unfortunately, this was not achieved, due to lack of time, but above all due to the absence of a revolutionary leadership with sufficient support among the masses. The workers required bold actions to solve the question of power. And finally, reaction resolved this question in its favour.

Wikimedia Commons

The fascist group Patria y Libertad was a small auxiliary force of reaction. This differentiates Pinochet fundamentally from the fascism of Hitler or Mussolini, who relied on mass fascist organisations to destroy the working class. For its part, Pinochet’s dictatorship used the state apparatus, the ‘rule of the sword’, in the manner of a Bonapartist regime. But it was a particularly cruel example, precisely because of the great strength that the workers had shown. In this sense, it was Bonapartism with fascist features.

The military were neither economists nor intellectuals. It was not until the arrival of the so-called Chicago Boys in 1975 that the regime adopted a distinct economic and political project. The dictatorship did not simply recover the lost positions of the bourgeoisie and imperialism, but transformed the social and economic structure of Chile under the so-called neoliberal model. The counterrevolution consolidated its project and dictated the 1980 Constitution.

The ideological and economic pillars of the system were established. The Labour Code with its anti-union laws put an end to sector wide bargaining. The denationalisation of copper allowed the concessioning of other state-owned companies. The pension system was privatised. Public education was municipalized and university education privatised. The forestry business was also handed to private profiteers. We could go on, but let us simply say that these policies left a horrendous legacy, and were challenged by the student movement of 2006 and 2011, and more recently by the rebellion of October 2019.

Exile played a decisive role on the left, in a process known as Socialist Renovation, influenced by the experience of the Stalinist regimes, Eurocommunism and the credit financing of European social democracy. The class collaborationism of Berlinguer’s “historical compromise” in Italy, was fundamental. So too was the “model transition” in Spain after Franco’s death.

In short, the Socialist Renovation tried to combine bourgeois democracy and ‘socialism’, while generating alliances with the centre, that is to say with Christian Democracy, abandoning the notion of class struggle and the seizure of power by the working class. The Socialist Party suffered a crisis and divisions in 1979 over this turn, but the Socialist Renovation was broadly accepted. However, despite this concession to reformism, to this day there are socialist tendencies, with more presence in the interior of Chile, which maintain their revolutionary traditions.

Until 1979, the Communist Party, whose leadership had not broken with the popular-front policy that led to the disaster, wanted to include the Christian Democracy in an “Anti-Fascist Front” against the dictatorship. But the Christian Democrats rejected them, and actually sought to isolate them politically. Influenced by communists in the GDR and the militant spirit of young communists at home, a strategy of Mass Peoples’ Rebellion was promoted.. That is to say, the path of the political defeat of the Armed Forces and not conciliation with the regime.

The fight against the dictatorship

In 1982, Chile suffered the greatest economic crisis since 1930. GDP fell 15 percent, unemployment reached 25 percent, and in some marginal areas it was up to 40 percent. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua and El Salvador, where some Chileans fought and received instruction, had some effect on the Chilean masses. 1983 marked 10 years of unbearable state of emergency and curfews. Something had to give.

These factors explain protests that took both the military and the political parties by surprise. The Confederation of Copper Workers (CTC) called for the First National Day of Protest on 11 May 1983. The demonstrations were massive and especially combative in the outskirts of Santiago. Professionals, merchants and transport workers also joined in. An organisation of women opposed to the dictatorship, MEMCH 83, also arose. Those unions willing to mobilise formed the National Workers’ Command (CNT).

The Democratic Alliance was created, which brought together the Christian Democracy, the renovated socialists, and some right-wing sectors, opposed to the dictatorship, which pressed for a quick negotiation. On the other hand, the Communist Party, more radical socialists, the MIR, and other leftist groups formed the Popular Democratic Movement. There was a competition between the “negotiated” alternative of the Democratic Alliance and the “insurrectionary” Popular Democratic Movement. A third option was to continue with the dictatorship, which contemplated a plebiscite in 1988 to affirm its control. Pinochet sought to buy time with fruitless dialogue, while unleashing indiscriminate repression and the selective elimination of opposition leaders.

A pre-insurrectionary mood threatened to overwhelm the negotiations. The Communist Party connected with the radicalisation in the working-class neighbourhoods, military cadres entered the country, and the Frente Patriotico Manuel Rodriguez (FPMR) was born.

The largest National Days of Protest took place on 2-3 July 1986, with a total stoppage. The groups that sought the political defeat of the Armed Forces called this the “decisive year”. But the seizure of arms sent from Cuba, a failed FPMR operation and a month later an attempt on Pinochet’s life failed. This constituted a logistical and moral blow that plunged the Communist Party and the FPMR into a crisis.

Thus, the negotiated solution triumphed, which gave rise to the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia, campaigning for the 1988 plebiscite. The NO vote (i.e., NOT to continue the dictatorship) won with 56 percent, against 44 percent for YES.

The agreed democratic transition was a compromise from above, to avoid the insurrectionary overflow from below. The dictatorship was oxygenated at decisive moments, avoiding its fall by revolutionary means. Impunity for the crimes of the dictatorship was established and the armed forces remained infected with torturers and murderers.

The Concertación, a coalition formed mainly by the newly founded Partido Por la Democracia, plus the renovated Socialist Party and Christian Democracy, managed the democratic aspirations of the Chilean people after the dictatorship. But they ruled keeping most of the legacy of the dictatorship intact, making the necessary superficial changes so that nothing changed. The same ‘neoliberal’ capitalist policies remained.

Ultimately, the coup took place not for the sake of having a dictatorship, but to protect capitalism from the revolutionary demands of the masses. Capitalism, and the economic policies of Pinochet, remained in place despite the removal of Pinochet himself from power.

Fifty years after the bloody coup d’état, Chileans still live with the legacy of that defeat. The uprising of 2019 represented a rejection of the entire regime created at the end of the dictatorship.

It is crucial to draw the necessary lessons from the Popular Unity government. The main one is understanding the class character of the bourgeois state, which cannot be used to gradually introduce socialism.