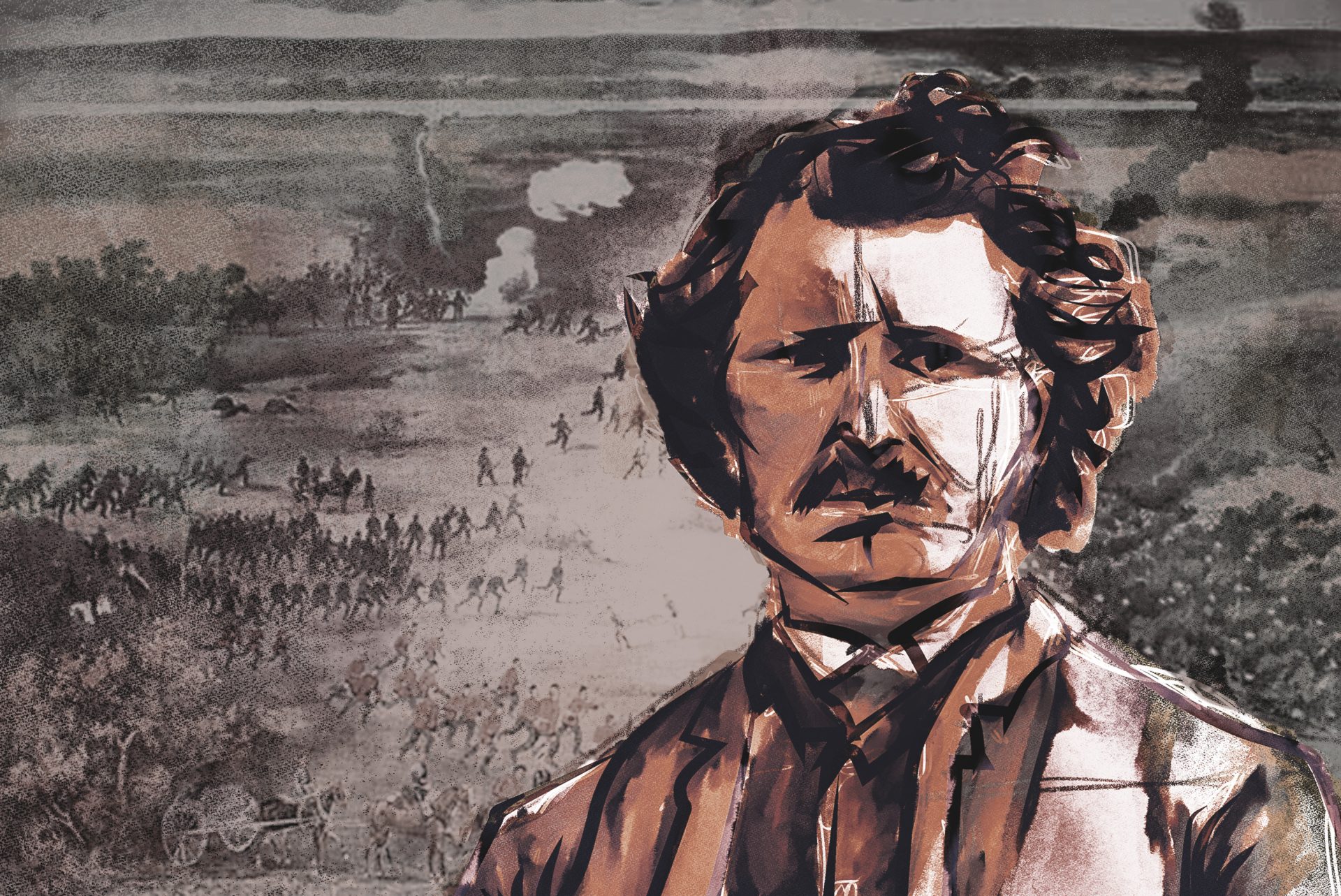

Official histories often portray Canada as a peaceful country where the path of compromise is preferred to the path of conflict. But this could not be further from the truth. In fact, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary events are at the heart of the foundation of Canada. And the struggle of the Métis, led by Louis Riel, is just one of these pivotal conflicts.

Officially founded in 1867, the creation of the modern state of Canada was not the result of a revolution, as with our neighbours to the south, but a vicious counter revolution. The process which led to the creation of the country began with the putting down of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions in 1837-38, and was completed with the crushing of the Métis resistance in the West.

While bourgeois historians referred to this movement as a simple “rebellion”, this slander could not be further from the truth. On the other hand, many describe this movement as a simple “resistance,” which while closer to the truth does not capture the true nature of what was going on. In our opinion this was a mass democratic revolution mirroring the rebellions of 1837-38, as we will show.

This revolution was only brought to heel through the use of deceit, subterfuge and an outright reign of terror under the government of John A Macdonald. While this occurred many years ago, it is important for workers and youth to understand these important events which occurred at the very birth of the country.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

Part One: The origins of the Métis

Who are the Métis? Métis, which literally means “mixed” is the same word used in Spanish in Latin America—Mestizo—to describe someone of European and Indigenous descent. However, the Métis in Canada are a bit more than this. By the early 19th century the Métis began calling themselves “La nouvelle nation,” they had their own flag, and the last battle in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 is known as the “Guerre nationale” in Métis literature.

The creation of the Métis as a distinct national group has economic roots. With the development of capitalism in Europe, the nascent bourgeoisie from England and France funded many expeditions into the land now known as Canada in search of natural resources. In this regard, the origins of the Métis are intimately connected with the development of the fur trade.

The French sent what was known as coureurs des bois (woodsmen) or voyageurs (boatmen and canoeists) into the vast country to establish connections with Indigenous peoples. Prior to colonization, Indigenous peoples had vast trade networks, knew the lay of the land and were skilled trappers and hunters. For the colonial powers vying for dominance in the fur trade, forging relations with Indigenous peoples was therefore of prime importance.

While at first there were only a limited number of coureurs des bois, this grew massively in the late 17th century with the increased European demand for felt hats made from beaver fur. In 1680, the intendant of New France, Jacques Duchesneau de la Doussinière et d’Ambault, estimated there were eight hundred coureurs des bois.

These men would quite often marry Indigenous women. In fact, this was, more often than not, the only way to develop a trade relationship. This was known as “mariage à la façon du pays” (marriage according to the custom of the country) and as Jean Teillet explains in her book The North-West is Our Mother: “The whole point of voyaging into the North-West was to trade with Indigenous peoples who supplied furs. To obtain the furs, one needed to establish a relationship with the bands. The best way to do that, sometimes the only way, was to marry one of their daughters. This was a general practice in the North-West.”

Brought into contact with Europeans, Indigenous peoples were also brought into contact with the developing world market. From this point on, the future development of Indigenous peoples was bound up with the development of world capitalism. Historically, the Métis people developed precisely out of the connection between pre-capitalist economic formations and the developing capitalist world. For a period of time, the Métis played a central role in this process.

By the 18th century there were thousands of voyageurs. The vast majority were sons of Indigenous women and European (usually French) men. But this in and of itself did not lead to the creation of a new nation. The reason is not difficult to see. While the voyageurs had started to develop a common culture (they were known for their songs and dress which was a mix of European and Indigenous), these ties were still far too weak at this point as they did not inhabit a common territory or speak a common language. Michif didn’t become a widely spoken common tongue until well into the 19th century. As well, many voyageurs were more or less integrated into and associated with the Indigenous groups which they had married into, and did not make up an independent social group. Even in terms of self-identification, the term Métis was not widely used until well into the 19th century.

Economic foundations of the Métis Nation

At root, big changes in the relations of production forced the Métis to think and act collectively and come together as the Métis. This process occurred in parallel with the economic development of Canadian capitalism, which set the Métis on a collision course with the burgeoning financial and industrial capitalists in the East.

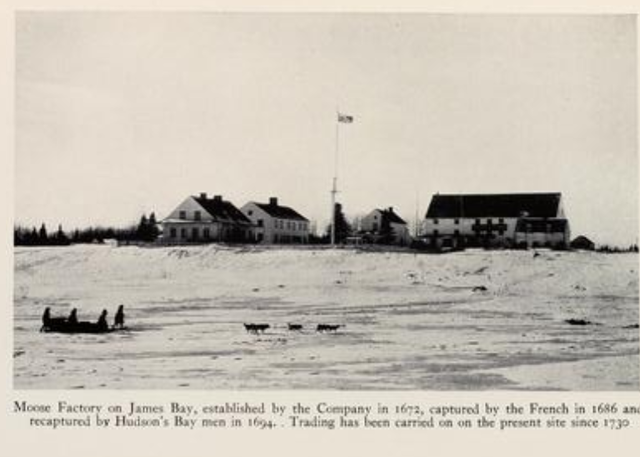

Capitalism in Canada was in a fledgling state in the 18th century. Through the colonial system, the British kept the territory intentionally underdeveloped. There was a merchant bourgeoisie which developed via companies like the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) who extracted resources for export back to Britain. In turn, commodities could only be bought from Britain.

As the population grew and local industry developed, the productive forces were increasingly hemmed in by the colonial system. In the early 19th century, the petty bourgeoisie in Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) tried to establish free trade and a democratically elected government. This was what was known as the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions of 1837-38. In the North-West the process was delayed as the population was much smaller and the capitalist economy much less developed. However, as the economy advanced, similar clashes took place.

Around this time, there were thousands of voyageur traders who increasingly moved westward into what was known as “Rupert’s land.” One of the key areas that was settled was known as Red River, around modern day Manitoba. They began intermarrying and creating a new culture and even their own language called Michif, which was a mix of Cree and French. The generation born around 1790 started to develop into a sizable, distinct social group apart from both Indigenous peoples and Europeans. This became evident as they started calling themselves the Bois-Brûlés (burnt wood). Later the name Métis was adopted.

By 1780-90 the beavers around the Great Lakes had been trapped to near-extinction and there was a concerted push into the North-West in search of furs. A group of Montreal merchants created the North West Company (NWC) in 1789 to seize the opportunity. This put them in direct competition with the HBC, which played the dominant role in the fur trade at the time.

While the HBC was content in staying near their forts on the shores of the Hudson Bay, requiring Indigenous traders to come trade with them, the NWC sent hundreds of voyageurs deep into the North-West. Soon, it became easier for Indigenous peoples to simply trade with the NWC voyageurs. This led to a bitter dispute between the HBC and the NWC which resulted in armed clashes on several occasions.

The governor Miles MacDonell attempted to impose HBC rules on the Métis and stop them from trading with the North West Company. The most famous of these was the Pemmican Proclamation of 1814 which placed an embargo on the export of pemmican, a traditional Cree food widely used in the North-West at the time. But the real power in Red River was the Métis, who were armed and made up 85 per cent of the population. MacDonell was just the first in a long line of governors who came to realize that any attempt to dictate to the Métis would be met with fierce resistance. This ultimately led to NWC agents taking MacDonell captive and bringing him to Montreal for trial.

This situation led to MacDonell’s resignation as governor in 1815. However, his replacement was no better. Robert Semple poured fuel on the fire of an already tense situation, leading an all-out assault on the NWC and the Bois-Brûlés. This conflict now saw the Métis start to move and act collectively.

Governor Semple set up a blockade at the forks with the intention of causing damage to the NWC’s supply lines. On June 18th, Brûlés leader, Cuthbert Grant led a force of 62 with 1,800 pounds of pemmican destined for a NWC brigade at Frog Plain. Semple led a party to confront Grant. In the resulting conflict 21 HBC men including Semple lay dead, while only one Brûlé was killed.

While there wasn’t a clear ideology to this movement at the time, by and large this was a petty bourgeois movement fighting for free trade against a colonial power. The outlines of this struggle would lead the Métis to similar ideological conclusions as the leaders of the Rebellions of 1837-38 or the American Revolution. It is true that the interests of the Métis overlapped with those of the NWC, however, the Métis were not so much fighting for one company or the other but against the imposition from Selkirk and the HBC and for the freedom to trade with whoever they wish.

The fallout from this event was massive. Both companies went to court which proved to be a futile way of resolving the dispute. This was because no number of court decisions, made hundreds of kilometers away in the East, could be enforced onto the Métis in the North-West. As a result, the judge was forced to exonerate the Métis which was a de facto recognition of the Métis as a power in the region. It was a victory!

Here we see an interesting confirmation of the Marxist explanation for the origins of the state. The state, when reduced to its fundamental characteristic, is armed bodies of men in defence of certain property relations. The formation of the state in the North-West was foreshadowed by the governing councils created by the HBC. However, as the HBC did not have sufficient armed bodies of men, they could not fully impose the dominance of the colonial system as was done in the East. The Métis were the main armed force in the region and this fact was taught to more than one HBC governor before this contradiction was resolved with the crushing of the Métis resistance and the establishment of the Canadian state.

The Métis had now come into their own and there was no putting the genie back in its bottle. Word of the victory at Frog Plain spread far and wide over the North-West and Grant became a hero almost overnight. Pierre Falcon, who was 23 at the time of the victory at Frog Plain, wrote a song about the event called “La Chanson de la Grenouillère,” which described the chasing away of the invaders. This became a celebrated song of the Métis all over the North-West.

With this, the Métis increasingly started to refer to themselves as La Nouvelle Nation. While it is always difficult to pinpoint exactly when a nation is formed, this was a key turning point in the foundation of the Métis Nation. Increasingly they had a common language (Michif), a founding event (the Victory at Frog Plain), a flag, a leader (Cuthbert Grant), a national poet and songwriter (Pierre Falcon), a common territory and more importantly a common economic base as bison hunters and fur traders.

The political economy of Red River

The economy of Red River was primarily based on the Buffalo trade and as early as the 1820s, the buffalo hunt was becoming a massive venture. The buffalo hunts increased in size and it became common for the communities in the Red River area to see their population depleted by nearly half during hunting season. Buffalo was such a mainstay of the economy at the time that it was common for a hunt to bring back 1-million pounds of buffalo meat from over 10,000 buffalo.

While the Buffalo hunt was a significant industry, in the beginning, the accumulation of capital was rare. The HBC set the level of demand, the prices, as well as how much they would purchase from each individual. This only allowed only the HBC to be capable of accumulating capital. The colonial system enshrined in the HBC monopoly completely controlled and limited trade. This outdated colonial monopoly was the political superstructure that the developing productive forces of the Métis Buffalo hunt was destined to collide with.

The internal dynamics of the Buffalo hunt were communal and egalitarian. Sharing was central to the Métis tradition due to the conditions of life in the region at the time. Starvation and famine were regular occurrences so sharing was a matter of survival, as the giver at one point may be the receiver at another moment. The Laws of the Hunt, included sharing of the Buffalo killed so that every family would receive enough to support itself. This was regardless of how many animals were killed by any one person. The hunt chief would traditionally make at least one pass through the herd and any animal that he killed would be given to the old and sick who were unable to hunt or be active in the productive process. This was very similar to traditions among various First Nations which most definitely influenced the Métis.

Agriculture was quite limited and crop failures were a regular occurrence. The HBC didn’t absorb much of the agricultural product of the settlement as the demand of the trading posts was relatively small and easy to satisfy. The company later depressed demand by maintaining large company-run farms to supply its forts. While some Métis did have farms, many abandoned agriculture for the Buffalo Hunt as it was a much more lucrative way of providing for one’s family. This was especially the case after 1844 when the American market opened up for trading and there was a massive increase in demand for Buffalo robes.

There were also a growing number of Métis wage labourers who worked for the HBC. In the 1830s there were approximately 260 “tripmen” working on what were known as “York Boats” (a big barge used to transport cargo). By the late 50s and early 60s this number had increased to over 1,000 tripmen. This was an integral role in the HBC’s transportation system since the HBC had built forts inland.

All of these factors combined to create a local economy which was generally geared towards subsistence. Remarking on the economic situation, William Keating who passed through Red River in 1823 noted that there were no cash transactions. It was instead some form of barter economy where wheat and other products would be “traded in the way of exchange with some other commodity.”

However, there was no escaping the spread of capitalism. The pressures of the world market inevitably would come to bear and this would have irreversible effects on the Métis and their coming struggle against the HBC and the Canadian state.

The struggle against the HBC

Red River in the 1830s and 40s was rife with talk of freedom, equality and a government elected by the people. These republican ideas came from France and America but more importantly the 1837-38 Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada. These ideas found a ready-made audience among the Métis who lived freely on the plains. The ideals and goals of the Patriots in Lower Canada (Quebec) resonated with the Métis so much so that they would commonly fly the Patriot flag and sing Patriot songs.

The idea that they should have a government elected by and responsible to the actual people who lived in the area instead of a government appointed by and responsible to people far off in Britain was simple enough to understand and struck a chord with the Métis who had been chafing under the undemocratic regime of the HBC. In addition, as the Buffalo hunt developed in connection with the developing capitalist world market, Métis traders chafed under the HBC restrictions and were yearning for free trade. Louis Riel’s father, Jean-Louis was an ardent supporter of Papineau, one of the principal leaders of the rebellion in Lower Canada (Quebec) in 1837. He had been in Lower Canada during the movement and this obviously had a big impact on his political views. Unsurprisingly, Jean-Louis Riel became one of the principal leaders of the movement against HBC rule.

Increasingly there were small conflicts here and there as the HBC tried to enforce their trade monopoly and impose other arbitrary measures. In 1834 a Métis tripman, Antoine Larocque, was struck over the head with a poker by an HBC officer for insisting that he get paid his wages in advance, a common practice at the time. The result was that hundreds of Métis surrounded Fort Garry singing war songs and demanding that the officer be handed over to them. The matter was only resolved when the HBC agreed to pay Larocque his wages without him making the trip. The Company was also forced to give Larocque a keg of rum and some tobacco for his troubles.

In 1835 the Métis protested against food shortages and succeeded in forcing the HBC to open their food storage to feed the population. Later they forced the company to pay a higher price for pemmican. In 1836 Louis St. Denis was flogged in public for exporting furs without a company license. The outrage at this was so strong among the Métis that the man who carried out the flogging was forced to flee for fear of his life.

Métis tripmen often conducted work stoppages, refusing to make the second trip to York Factory. In the end, the Company resolved the strike but only by giving in to many of the strikers demands. The mood among the workers was so angry that the Company had to call in Cuthbert Grant, (who had betrayed the movement in accepting an HBC post) to bring his authority to bear and personally escort the boats to keep the peace.

All of these small victories made the Métis very conscious of their collective strength. While different layers of the population didn’t necessarily have the same grievances, they were all generally united in their struggle against colonial rule and the HBC. This feeling persisted well into the 1850s and in 1857 governor Simpson wrote “The whole of the population of the Red River, with very rare exceptions, is unfavorable to us.”

The trial of Pierre Guillaume Sayer

When the American fur market opened up to the region in 1844 with the establishment of a trading post in Pembina just South of the border, this created an entirely new situation. The full brunt of the world market now came to bear. Métis traders now had the opportunity to come into their own. In Marxist terms, the young budding petty bourgeois layers could now accumulate capital and become bourgeois. However, in order to do this, they had to first break the Hudson Bay Company monopoly.

When the Métis traders started trading with the Americans, the HBC again tried to stop this by imposing stringent regulations. This led to the stationing of British troops in the settlement in 1845 to help impose the regulations and forcibly seize illegal goods. While this seemed to work to dissuade Métis from trading with the Americans, this was no long-term solution.

The Métis, contrary to lies spread about them, did not resort of violence on a whim. They tried every avenue possible to avoid violent confrontation and plead their case before the HBC. They drafted constant petitions which generally contained the same message. For example, one petition in 1846, contained the signatures of 977 Métis and demanded free trade, a government independent of the HBC and an elected legislature. This petition was drafted by a fur trader named James Sinclair and taken all the way to London where it was subsequently ignored.

As soon as the troops were withdrawn in 1848, Métis traders resumed trading with the Americans. This economic situation inevitably led to another pivotal event: the trial of Pierre Guillaume Sayer.

Sayer and three other Métis traders were arrested by the Council of Assiniboia for fur trafficking in 1849. The setup for the trial was a complete farce. The judge Adam Thom was an HBC employee and one of the main authors of the Durham Report—which called for the forced assimilation of the French. He had been against any concessions to the Patriots during the 1837-38 Rebellions and afterwards called for the execution of 750 patriots. He refused to speak French, even though the majority of the population were Francophones. He was therefore hated by the Métis, and rightly so.

The entire jury and the prosecutor were HBC employees or loyalists and therefore the result of the trial was clearly a foregone conclusion. Anything short of the prosecution and punishment of Sayer and the Métis traders would set the precedent that it was acceptable to defy the HBC monopoly. The trial took place on May. 17, 1849 and found Sayer guilty of illicit possession of furs. However, a verdict is useless if it cannot be enforced.

Thom had intentionally scheduled the trial on Ascension Day (a Catholic holiday), with the aim of guaranteeing that most of the Francophone Métis (who were generally Catholic) would be in Mass and therefore not able to interfere with the trial’s proceedings. This backfired however and on the day of the trial, a young Jean-Louis Riel, persuaded the priest to hold an early Mass where he made a rousing speech appealing for the Métis to challenge the company’s monopoly and go to the courthouse. About four hundred armed Métis surrounded the court house.

They presented a petition which demanded:

1) The removal of Thom

2) Equal use of French and English in the courts

3) Rescission of the law restricting imports from the United States

4) Appointment of Métis to the Council of Assiniboia

5) Free trade in furs

Thom responded that they would not be receiving “delegates of the people.” However, with hundreds of angry armed Métis outside, while Sayer was technically found guilty, he was given no punishment and the charges against the other three Métis traders were dropped. Sayer was even given back the furs that he was supposed to have illegally trafficked. While on paper the company monopoly was still in effect, in practice it has been decisively broken. The productive forces had rebelled against the old relations of production which were burst asunder.

When the prosecutor announced that he would not seek punishment, the crowd chanted: “Le commerce est libre!” “Vive la liberte!” “Paashkiiyaakanaan!” (we won!). Jean-Louis Riel emerged from the courthouse with Sayer on his shoulders and the crowd went wild, cheering and firing shots into the air.

The fall out, just as in 1816 with the Victory at Frog Plain was huge. Everyone was forced to accept the reality. Even Thom was forced to speak French in court! The Council of Assiniboia reduced tariffs on American goods to make it equal to the tariff on British goods and agreed to appoint more Métis to the Council.

The name Riel, just like Grant had been previously, became synonymous with Métis resistance and Métis victory. Louis Riel, who was just five at the time, was present at his father’s speech and it left an indelible impression on him.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four