This is the first of a two-part article.

On Feb. 11, 1969, the Montreal police violently put down one of the largest student occupations in Canadian history. For two weeks, as many as 300 students had peacefully occupied the computer centre at Sir George Williams University to protest a racist professor’s treatment of Black students, and the administration’s complicity in defending him. As police descended on the occupation, however, a riot broke out. Students broke windows and threw punch cards by the thousands into the streets below, they smashed computers with fire axes, and in the confusion someone started a fire which nearly engulfed the entire ninth floor of the building.

The occupation was brought to an end by the violent repression of the state, and for months afterwards a waterfall of slander poured from every mouthpiece of the bourgeois media onto the unfortunate students who had dared to fight against their oppression. Only recently, after more than 50 years of silence, has Concordia University (inheritor of the Sir George Williams campus, and its legacy) issued an apology in the hopes of cleansing itself of this distasteful history—but it is far too little, and far too late.

The legacy of the Sir George Williams affair does not belong to Concordia University and its administration, but to the revolutionary workers and students who, to this day, are fighting racism and all other forms of discrimination and oppression. This was an inspiring struggle whose repercussions were felt internationally. In Trinidad, the affair acted as a spark for a series of mass protests against British and Canadian imperialism and Trinidad’s Black Power Revolution of 1970. We must draw the necessary lessons from its successes and from its eventual defeat.

Revolutionary times

To understand the Sir George Williams Affair it is first necessary to understand the historical environment in which it took place. Quite often it is the youth who are most sensitive to the broad social changes going on in society around them. The students studying at Sir George Williams in 1968-69 were no exception.

The late 1960s were a period of great revolutionary fervour. The relative stability of the postwar era was turning over into a wave of revolutionary struggles all over the globe. Mass protests of workers and youth swept through Italy, West Germany, Brazil, and Mexico, among other countries. Meanwhile, a general strike in France placed power at the feet of the French working class, forcing then-President Charles de Gaulle to flee the country. All over the world, the late 1960s and early 1970s marked a period of violent class struggle. An important episode in this struggle was to take place in Quebec.

Quebec had been dominated by foreign imperialism since the 18th century—first by the British and then by American and Anglo-Canadian capitalists. A series of militant strikes in the 1950s were foreshocks to a coming reckoning with this foreign domination. These ushered in the Quiet Revolution and marked the beginning of the modern national liberation movement in Quebec. In 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec won a historic election victory, putting an end to the “Grande Noirceur” (Great Darkness), a 15-year period of domination by the conservative Union nationale regime. Through a series of reforms—the nationalization of hydroelectricity under the slogan “maîtres chez nous” (“masters of our own house”), the creation of state-owned corporations like the Société générale de financement, among many others—the ground was cleared for the development of a national Québécois bourgeoisie. But none of these reforms fundamentally addressed the issues faced by the workers and youth of Quebec.

By the mid-sixties, the Quiet Revolution had reached an impasse. Inflation and unemployment were rising, and, as a result, the class struggle was coming again to the forefront. Across the province, thousands of workers went on strike for better wages and conditions. In 1968, students joined the struggle, with tens-of-thousands taking to the streets to protest the underfunding and mismanagement of the CÉGEPs (publicly funded colleges) which had been formed only the year before. This rising tide of class struggle would eventually culminate in the 1972 Common Front Strike when the workers of Quebec brought capitalism in the province to its knees.

This was the environment in which the events at Sir George Williams would take place, and it is an essential part of understanding the Sir George Williams Affair. Historian Dennis Forsythe, writing in 1971 explained:

“Quebec, and Montreal specifically, is like a machine creaking at its seams, as witnessed by the increasing frustrations and resentment expressed by almost all segments of the society. In the last three years, policemen, teachers, taxi-drivers, post-men, anti-poverty groups, students, and women have all entered into the ‘long march’ here in Quebec… One could place the Sir George Williams Affair within this long line of protests, as expressive of the pent-up grievances and frustrations experienced by blacks.”

Meanwhile, as mass protests and revolutions unfolded all over the world, the United States, the heart of world imperialism, had a revolutionary struggle of its own. The struggle for Black liberation, which had begun with the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s, was reaching revolutionary conclusions. In the “long, hot summer” of 1967, 159 race riots swept across the United States in only a few months. Black leaders like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were assassinated, and in their wake followed militant organizations like the Black Panthers, led by revolutionaries like Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, and Fred Hampton.

Inspired by the Colonial revolutions of the 1950s and 1960s, the Black Panthers organized an armed, revolutionary resistance to the violent oppression of Black people by the police, and in doing so became a point of inspiration for workers and youth all over the world—not least of all in Quebec.

Racism in Canada

In Canada the ruling class has long tried to cultivate a progressive image for itself—a place in which everyone is given equal opportunity to succeed. This comforting illusion of a “humanitarian” Canada, however, is shattered by the real facts of Canada’s history: by the mass graves of Indigenous children on residential school grounds, the internment of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War, and the forced relocation of Black Canadians from the east-coast community of Africville and the demolition of their homes to make way for industrial development, along with many other examples. While Canadian history textbooks tend to approach the issue of anti-Black racism as something applicable only to our neighbours to the south, this only serves to prettify the ugly face of racism in Canada.

Well into the 20th century, the provincial and federal governments refused to hire Black employees, and the same was true for whole swaths of private industry. Universities routinely rejected applications from Black students on the basis of race, and Black workers were overwhelmingly forced into menial jobs as domestic servants, labourers, janitors, waiters and railway porters, receiving pay significantly beneath the rest of the Canadian workforce. Black communities often settled into distinct neighbourhoods, like Africville outside of Halifax and Little Burgundy in Montreal, where they would frequently organize community groups based around mutual support to help bear the weight of their severe exploitation collectively.

For most of the 20th century, the Canadian government maintained the right to forbid “non-assimilable immigrants” (i.e. non-European immigrants) from entering Canada. This only began to change with the “West Indian Domestics Scheme”, a program that allowed Caribbean women to apply for temporary or permanent residence if they spent one year working as domestic servants. Canada would open its doors to migrants from the Caribbean, but only on the condition that they take the most menial and worst-paying jobs. In the end, Canada finally removed race from its immigration criteria in 1962 leading to an influx of Caribbean workers and students in major Canadian cities. For example, Montreal’s Black population grew between 1961 and 1968 from 7,000 people to as many as 50,000.

An almost ubiquitous problem faced by Caribbeans arriving in Montreal was that of finding a home and a job. One student, arriving from Trinidad and Tobago, was told by a Montreal landlord: “I don’t rent to n—–s”. It was the first time he had ever been called the word. The same was true when looking for work. Black workers, especially those born outside of the country, were systematically barred from jobs for which they were qualified and were treated as disposable in the menial industries that would hire them.

Those who arrived immediately took on the burden of discrimination and racism. Work, life, and school became, for many, a daily exercise in degradation. The ability to endure this degradation quietly, with gritted teeth, could not be carried on by everyone forever. At a certain stage, it was bound to burst through the apparent calm of the status quo and cause eruptions of anger and resistance. Sooner or later social explosions were inevitable. All that was needed was the proper spark.

The Anderson Affair and Sir George Williams University

The first choice for most English-speaking students in Montreal was McGill University—one of Canada’s oldest and most prestigious institutions. In addition to demanding exceptional grades, however, the admission requirements for the university often reflected the prejudices of the upper echelons of Canadian society. For example, until the 1930s the university maintained a quota on the number of Jewish students it would accept, and it actively discouraged the hiring of Jewish faculty. In the 1960s, while a handful of Caribbean students were granted admission, the overwhelming majority were rejected. Their other option, Sir George Williams University, had a very different history. Beginning in 1926 with a series of adult education courses put on by the local YMCA, it eventually developed into an accredited university and moved into its downtown campus in 1966. For a large number of students, Sir George Williams offered a chance for a higher education that would not have otherwise existed. But even this “metropolitan” university was not immune to the prejudices of Canadian capitalism.

In the biology department at Sir George Williams, there was an assistant professor named Perry Anderson, who taught a prerequisite course for entry into medical school. Anyone at Sir George Williams who had the intention of becoming a doctor first had to pass through the classroom door of Perry Anderson. Unfortunately, many students found in his class an insurmountable obstacle: discrimination against Black students.

In the 1968 academic year, most of the Black students attending Anderson’s class were regularly failing his assignments. The consensus among them was that Anderson had never given a Black student a grade higher than a “C”, regardless of the quality of their work. Meanwhile, though he referred to most of his students by their first names, he refused to use the first names of the Black students in his class. Instead, he referred to them always as “Mr. Ballantyne”, “Mr. Frederick” etc. In one revealing incident, Terrence Ballantyne, a Trinidadian student, let two other non-Black students copy his lab report word for word. All three reports ended up on Anderson’s desk, and when they came back, the two students who had copied Ballantyne’s work received perfect marks. Ballantyne received 70 per cent. Eventually, these students reached their breaking point.

Six of them formally accused Perry Anderson of racism. A private meeting was arranged between the students, Anderson, and members of the administration. The administrators, it was said, were to act as neutral arbiters between the students and Anderson, and would be the ones to judge what steps would be taken next. The students stated their complaints against Anderson and provided their evidence, but to their surprise, found that wherever Anderson could not defend himself, the administrators defended him. No one took minutes, recorded evidence, or even wrote down the students’ concerns. Behind closed doors Anderson was absolved of all wrongdoings, and the “Anderson Affair” was buried.

The affair remained buried for several months. Their anger remained, but the students had learned that it was impossible to address the issue of racism on the campus through the bureaucratic channels of the administration. Instead, the students spoke with their classmates. It did not take long for an advisor at Sir George Williams to notice a change. Suddenly all of the Caribbean students who walked through her office door were discussing the serious issue of racism on campus—Anderson’s name became secondary. The real issue was the administration as a whole.

The battle of the hearing committee

In October of 1968, an international conference was organized in Montreal. The Black Writers Congress brought together revolutionaries from across the Caribbean and the Americas to discuss the issue of Black liberation on an international scale. Hundreds participated, among them Kennedy Frederick and Roosevelt “Rosie” Douglas—two students from Sir George Williams and McGill respectively. Douglas had been one of the key organizers of the congress, while Frederick had been one of the students to go through Anderson’s class and the meeting with the administration. There the two met and began working together. The inspiration of the congress and their new connection to revolutionaries like Douglas provided the Caribbean students at Sir George Williams with a new sense of direction. Henceforth, the administration would be treated with distrust—the students would rely on their own strength.

Towards the end of 1968, Frederick led a group of fellow students to the principal’s office to demand that he reopen their case against Perry Anderson. The case was begrudgingly reopened, and the University was forced to formalize its process for dealing with the students’ complaints. No longer would matters be settled behind closed doors in private meetings. Instead, there would be an appointed hearing committee, composed of faculty members agreed upon by both parties, who would hear the evidence of the case and arrive at a verdict in a public hearing. This committee was composed of five professors: two Black, two White, and one from South Asia. The students and Anderson both agreed on its composition, but within the administration and certain layers of the faculty there was a deep sense of unease.

The hearing committee was seen as a threat to the administration. If the case against Anderson was allowed to be reopened and he was found guilty of discriminating against his students, then this would reveal their utterly inappropriate handling of the affair months before, and the administration’s disregard towards cases of discrimination in general. Similarly, there were some who worried that if Anderson were found guilty and disciplined (and he would have to be disciplined) it would set a precedent for the rest of the administration and faculty. A whole stream of new accusations could quite easily follow close behind.

Members of the administration began planning an “open” meeting with the intention to overrule and disband the hearing committee altogether. They sent invitations to staff and students, but by some remarkable happenstance none of the original complainants received an invitation—as a matter of fact, no Black student at Sir George Williams was invited!

When the students caught wind of the meeting they arrived with their supporters. They made speeches denouncing the administration’s attempt to go behind their backs. Tensions flared, and a physical fight was only narrowly avoided. The administration failed to dissolve the committee but had managed to discredit themselves in the eyes of the students and of a growing layer of staff. This created for them a serious and escalating issue.

Members of the faculty were voicing their support for the complaining students. It was necessary to curb the spread of these sentiments and to try to sew rifts between the students and the faculty. To accomplish this the Principle, O’Brien, sent a memo to every member of the university’s staff in which he warned that the complaining students were becoming erratic, and that soon they may turn to violence. His goal was to stir up whatever prejudice and paranoia he could, and so to head off any further support before it could crystalize.

Frederick and four others barged into O’Brien’s office and refused to let him leave until he wrote them a formal apology. O’Brien signed the apology, but then promptly filed charges against Frederick and the other students for kidnapping! The administration’s campaign of slander intensified.

Meanwhile, the hearing committee was crumbling under its own weight. The two Black professors were crushed between the interests of the administration and the students until they both resigned from the committee. Adamant in absolving Anderson, and by proxy themselves, of all wrongdoing, the administration packed the committee with people who they knew would side with Anderson. What they could not dissolve, they decided to co-opt.

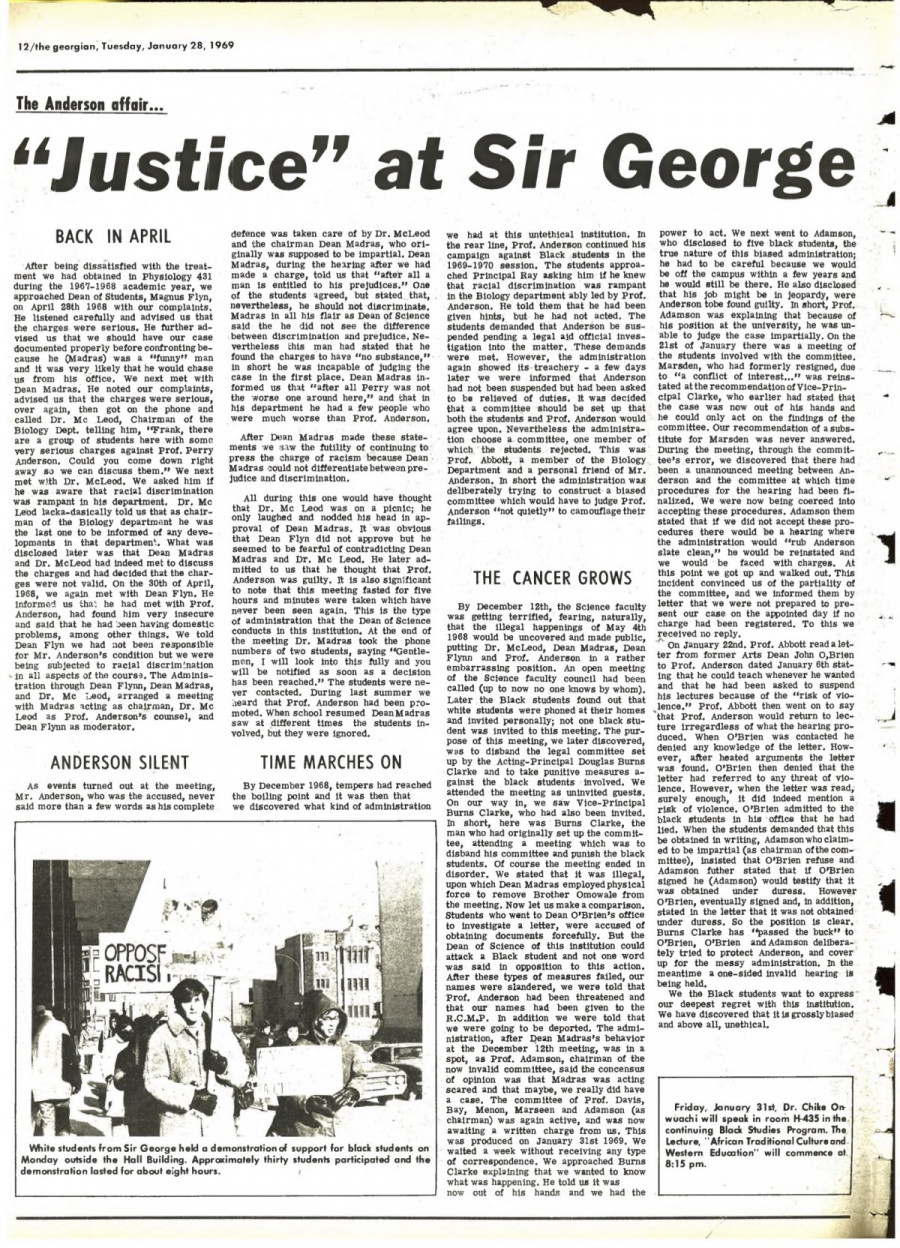

The students meanwhile countered the bureaucratic maneuvers and the public slander of the administration by organizing rallies and teach-ins on the university mezzanine. They mobilized hundreds of students from among the Sir George Williams student body and the student newspaper even dedicated an issue to the defence of their case. By mobilizing support from all racial backgrounds, and channeling this support into rallies and other demonstrations, they were able to cut directly across whatever slander was levelled against them.

For all its supposed authority, the administration was powerless. By mid-January, they fled to the Mont Royal hotel out of fear that their offices would be occupied by angry students. The administration had won its committee, but the students were taking the campus.

We need to understand that at that point, the battle on campus was no longer a local conflict, but was becoming an event of national importance. It was attracting the hatred of the racist ruling class. For instance, a Conservative MP from Alberta had demanded in the House of Commons that the Caribbean students be deported! They were clearly afraid about the confrontation becoming a point of expression for the struggle against racism across the country.

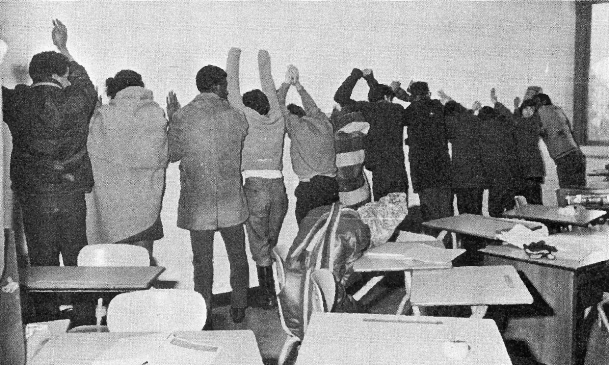

On Jan. 29, the long awaited public hearing commenced. The room was packed with students who one after another made speeches against the administration, calling for the creation of a new committee agreed upon by both parties. Even Rosie Douglas spoke, explaining how a few days before he had seen a sign posted in the university cafeteria that had said “n—–s go home”. After hours of speeches from the students, Frederick took the floor. He called on “everyone who wants to stand up for their rights, to stand up for justice” to follow him and to occupy the computer centre. He and 200 other students stormed out of the hearing. As they left, some stood up on chairs and called on their peers to follow them to the occupation. The amphitheatre was emptied.

As the students marched towards the computer centre, the administration, once again, absolved Anderson and themselves of all wrongdoing. Their only problem: no one was there to hear it. The 14-day occupation had started.