The following document is the product of over 20 years of study and participation in the fight of Indigenous peoples against Canadian capitalism. Over the years, we have learned from real-world struggle, and have detailed these experiences on the www.marxist.ca website. Revolution not Reconciliation encompasses the accumulated conclusions of the supporters of the International Marxist Tendency, Indigenous and non, applying Marxist theory to the movement on the ground. This process culminated in the 2019 Fightback/La Riposte Socialiste congress, where a draft version of the document was discussed, amended, and adopted, as the official position of the IMT. Here we detail a revolutionary Marxist analysis of the origin of Indigenous oppression, in opposition to the liberal/reformist hypocrisy of “reconciliation”, and the trap of identity politics and postcolonial theory, pushed by comfortable academics. The conclusions of this work have never been more timely, given the recurring explosions of Indigenous struggle in 2020. Only through mass revolutionary struggle against capitalism can all the oppressed be genuinely liberated. We appeal to all to study these lessons, discuss the conclusions, and unite with us in struggle.

— Oct. 21, 2020

This document is available for purchase in our bookstore. If you support these ideas, we encourage you to buy a copy, and to get involved.

As a defining feature of Canadian capitalism, the oppression of Indigenous peoples is of prime importance for Marxists. Most people exit the public education system with little exposure to the shameful history which underpins the Canadian capitalist system: one of violence, theft, and genocide against Indigenous people, which includes First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. According to bourgeois history, Canada’s relationship with the Indigenous peoples present in this land prior to European settlement is often depicted as cooperative and collaborative, while the American historical experience is portrayed as confrontational and violent. This has been used to promote a historical narrative of “peaceful cooperation” between the Canadian state and Indigenous peoples.

A look at the social conditions of many Indigenous communities today presents a starkly different picture. Despite decades of promises by both Conservative and Liberal governments, little has been done to improve the quality of life of Indigenous peoples on or off the reserves, or to repair the impact of generations of trauma inflicted by the state. Indigenous people are one of the most oppressed groups in Canadian society and continue to experience social maladies at rates far worse than the rest of the population.

Living and social conditions on many reserves are appalling. Canada as a whole routinely ranks among the top 10 nations in the world in terms of the UN Human Development Index. However, if these indexes were applied to Indigenous people alone, Canada’s position would be considerably lower, on par with many so-called Third World countries.

For example, despite the fact that Canada has the world’s third-largest supply of fresh water, water on many First Nation reserves is undrinkable or must be boiled before consumption. According to Indigenous Services Canada, there are currently 60 communities with long-term water advisories; this is down from 105 in 2015, but many more water systems on reserves are at risk of collapse.

In Neskantaga, a remote fly-in reserve in northern Ontario, people have been boiling water for more than 20 years after a water treatment plant that was built in 1993 broke down. Then there is Grassy Narrows, a northern Ontario community near the Manitoba border, which has lived with the effects of mercury in local lakes and rivers—the result of a commercial dump in the 1960s that has never been cleaned up. As a result, more than 90 per cent of residents currently display signs of mercury poisoning.

Housing on many reserves is in a deplorable state due to overcrowding and disrepair. The Assembly of First Nations estimates a shortage of 85,000 units countrywide. Overcrowding is six times higher on reserve than off. Of the housing already in place on reserves, just over 41 per cent need major repairs compared to seven per cent outside reserves, leaving thousands of Indigenous people living in hazardous conditions with a serious impact on health, education, etc. For example, poor housing and overcrowding is believed to be a significant contributing factor in the spread of tuberculosis, which has led Nunavut to have a TB rate 38 times the national average.

Poverty and unemployment are also higher for Indigenous people both on and off reserves. According to Statistics Canada, more than 80 per cent of reserves have a median income below the poverty rate, and the median income for Indigenous people both on and off reserves is 30 per cent lower than the rest of the population.

The median annual income for Indigenous people is just over $22,000, compared with the national average of around $35,000 for individuals in the general population. For First Nations people living off-reserves, the median income was about $22,500, compared to just over $14,000 for First Nations people living on reserves. At the time of writing, the unemployment rate among Indigenous people is 13 per cent, more than twice the rate among the non-Indigenous population.

(The Star, 2010)

Indigenous women make up the poorest section of Canadian society. Forty-four per cent of Indigenous women living off reserves live below the poverty line. The poverty rate rises to 47 per cent amongst on-reserve women. The average annual income of an Indigenous woman is only $13,300. Poverty forces Indigenous women into situations or coping strategies that increase their vulnerability to violence, such as hitchhiking, addictions, homelessness, sex work, gang involvement, or abusive relationships. Sexism and racism in capitalist society compound this vulnerability. There is a crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada, with between 1,200 to 4,000 lost sisters in the last three decades alone.

Incarceration rates for Indigenous people are severe compared to the rest of the population. Data released by Statistics Canada shows Indigenous youth made up 46 per cent of admissions to correctional services between 2016-17, while making up only eight per cent of the youth population. In Saskatchewan, 92 per cent of incarcerated male youth are Indigenous and 98 per cent of incarcerated female youth are Indigenous.

While Indigenous people make up around four per cent of Canada’s population, more than 23 per cent of the inmate population in federal institutions are Indigenous people. This amounts to an incarceration rate 10 times higher than among the non-Indigenous population. Indigenous adults make up the greatest proportion of admissions to jails in Manitoba at 74 per cent, and in Saskatchewan 76 per cent, while Indigenous adults only make up 15 per cent of the population in Manitoba and 14 per cent in Saskatchewan.

Around half of First Nations children live in poverty, but poverty rates reach as high as 62 per cent in Manitoba and 64 per cent in Saskatchewan. The poverty rate is 15 and 16 per cent among non-Indigenous children in these provinces respectively.

An Assembly of First Nations school survey showed that an estimated 47 per cent of First Nations currently require a new school building. Approximately 74 per cent of First Nations schools need major repairs related to requirements for additional space, plumbing and sewage issues, electrical, roofing, building code issues, and structure and foundation. Only 46 per cent of First Nations schools have a fully equipped gym. Only 37 per cent have a fully equipped playground or outdoor playing field. Only 52 per cent have a fully equipped kitchen and only 18 percent of First Nations schools have a fully equipped science lab. Only 39 per cent of First Nations schools have a fully equipped library. Only 48 per cent of First Nations schools have fully equipped technology, and only 67 per cent report good connectivity.

The bleak conditions faced by Indigenous communities and the legacy of colonialism have dire mental health implications. Suicide and self-inflicted injuries are the leading causes of death for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years of age according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. The overall suicide rate among the Indigenous population is double that of the total Canadian population; among Indigenous youth, the suicide rate is five to six times higher than non-Aboriginal youth.

The suicide epidemic affecting First Nations communities across Canada has been a national crisis for decades, but it attracted international headlines after three Indigenous communities were moved to declare a state of emergency in response to a series of deaths. In the spring of 2016, Attawapiskat First Nation reserve in Ontario declared a state of emergency after 11 young people tried to commit suicide in one night—adding to an estimated 100 attempts made over 10 months among this community of 2,000 people. Not long after, it was revealed that six people, including a 14-year-old girl, had killed themselves over a period of three months in the Pimicikamak Cree Nation community of northern Manitoba. In the aftermath, more than 150 youths in this remote community of 6,000 were put on suicide watch.

Indigenous community leaders and youth activists have long explained the cause of this epidemic to be a sense of hopelessness among the youth due to a lack of resources and opportunities on reserves, compounded by discrimination and intergenerational trauma resulting from colonial oppression. The demands of the communities living with this suicide epidemic focus on access to social services and cultural and recreational programs, improved education and access to training and employment. Yet federal funding continues to fall short and Indigenous communities across the country are left without the resources they need to address this epidemic.

How can this state of affairs be explained and what are the solutions? We have to understand the root of these problems in order to fight them. Whenever we are attempting to analyse a present-day circumstance, event, or issue, we must begin from this vantage point: what are the social and historical conditions that have led to the present situation? This requires a study of the development of Canadian capitalism, which was founded and built on the brutal exploitation and colonization of Indigenous peoples. A study of this history also clearly shows that the continued oppression and suffering of Indigenous peoples today is inherently linked to the capitalist system, and points the way forward for emancipation through the fight for the socialist transformation of society.

Rich and varied cultures thrived before colonization

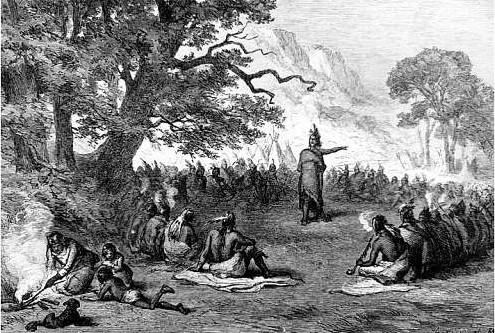

In what is now Canada, there had been several thousand years of human habitation, struggle and achievement before European colonization. When the European invaders first arrived there were more than 53 languages spoken from 11 main language families, with many variants and dialects. It is not possible to do justice to the rich variance of culture, language and traditions of the different Indigenous peoples in this text.

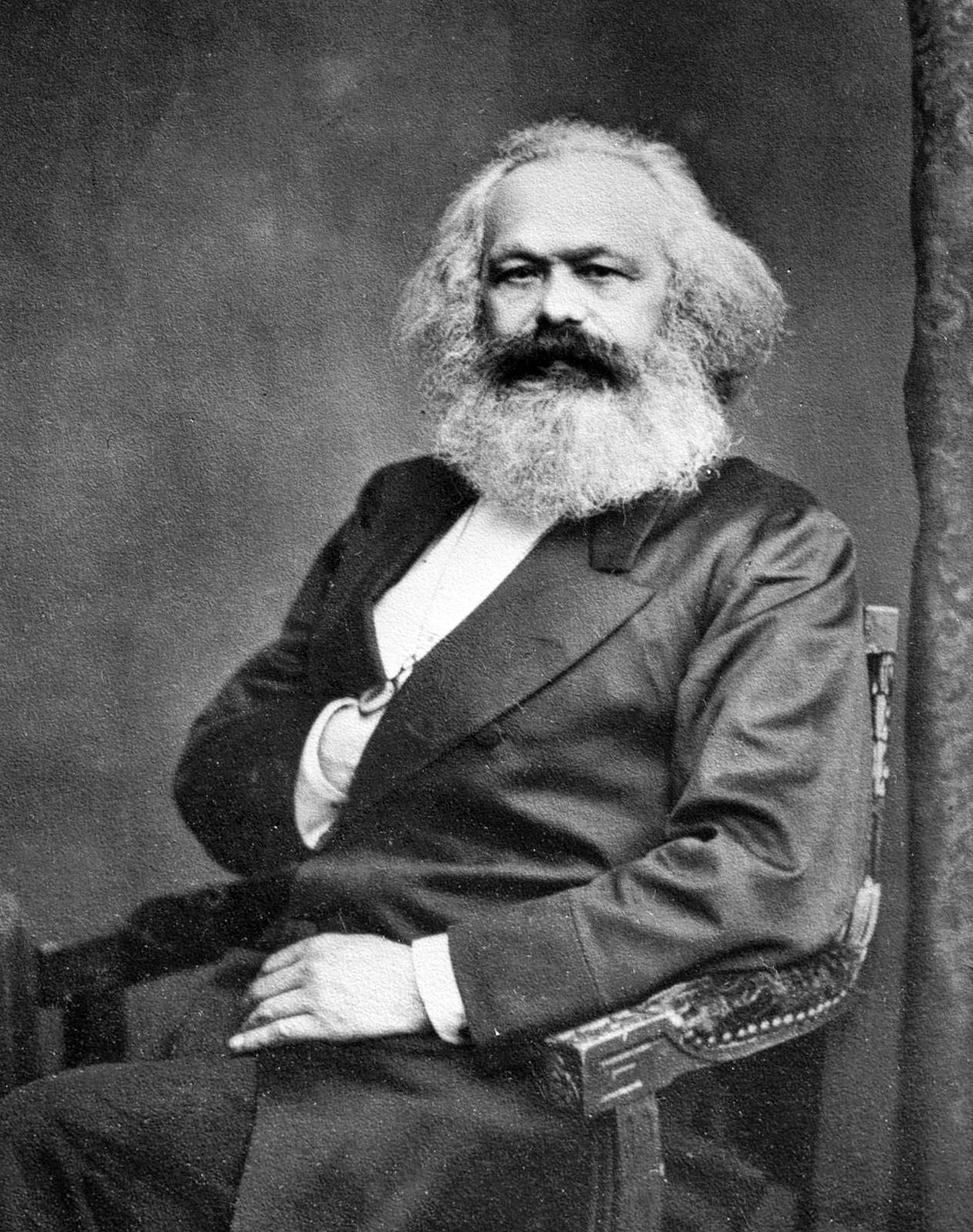

However, there were some common and recurring features across many Indigenous peoples that result from a similar organization around production and exchange. The structure of society that prevailed prior to colonization was what Friedrich Engels referred to as primitive communism.

While many academics have attacked the term “primitive communism” on the basis that this somehow denigrates Indigenous people, this is a complete misunderstanding of the term and was not in any way Engels’ or Marx’s intention. The original German word for this is Urkommunismus, which more correctly means the “first”, “original” or “primeval” communism. This term denoted a stage of society in which the productive forces, and therefore the productivity of labour, are not sufficiently developed to produce a stable surplus—the prerequisite for the development of class society and the state apparatus needed to defend it. This analysis is in no way meant to disparage Indigenous peoples, as every human society inevitably went through a similar phase and an honest reading of Engels would show that he spoke positively of the traditions of Indigenous communities, which in general were much more egalitarian than the capitalist “civilization” we live under today.

The organization of society under primitive communism is egalitarian and based on communal ownership of hunting and fishing grounds. Private property is limited to personal items. In the absence of class division, the state as a separate machinery of force for maintaining class rule does not yet exist.

As Métis Marxist Howard Adams explained,

Before the Europeans arrived, Indian society was governed without police, without kings and governors, without judges and without a ruling class. Disputes were settled by the council, among the people concerned. Indian government was neither extensive nor complicated, and the positions were created only to ensure effective administration for a given period of time. There were no poor and needy in comparison with other members, and likewise no wealthy and privileged; as a result, on the prairies there were no classes and no class antagonisms among people. Members of the community were bound to give each other assistance, protection, and support, not only as part of economics, but as part of their religion as well. Sharing was a natural characteristic of their way of life. Each member recognized his or her responsibility for contributing to the tribe’s welfare when required, and individual profit-making was unknown. Everyone was equal in rights and benefits.

These societies also tended to be matrilineal, with the family being traced through the female bloodline and women occupying the head of the household and having powers to elect and dispose of war chiefs.

However, it is important not to view Indigenous peoples as a monolithic bloc. As Engels explained in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, primitive communist societies are not static and pass through various stages of development. Among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, there was a wide variance in terms of socioeconomic development and ways of life. For example, the Haudenosaunee (“People of the Longhouse”, “Iroquois”, or “Six Nations”) of the Great Lakes region were agriculturalists, growing beans, squash, pumpkin, corn, and sunflowers. Instead of the temporary encampments characteristic of hunter-gatherer societies, they built large villages with permanent longhouses.

The cultivation of crops began to make possible for the first time the production (and storage) of a surplus of foodstuffs. This in turn led to trade by barter, and a wide trading network had developed prior to the European invasion. Various Indigenous peoples began to specialize in the development and trade of certain resources or products, including agriculture; hunting and the skin and fur trades; fishing, whaling and seal hunting; canoe production, bow production, tobacco farming, horse trading, iron and metal extraction, etc.

There is ample evidence of widespread trade throughout the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans. Corn spread throughout the Americas via the complex Mayan trade network. Pipestone was traded extensively, and pipestone smoking artifacts have been found throughout the United States and Canada. The only pre-contact pipestone quarry was located in Minnesota. There is extensive evidence of widespread trading between Indigenous peoples on the West Coast of North America—trade in blankets, belts, skins, snowshoes, fish, baskets, paint, knives, iron and metals, and horses.

Along with these increasingly complex productive relations arose more complex social organization. Around the year 1570, the five Haudenosaunee tribes (Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Mohawk) united in a confederacy that has endured for hundreds of years: the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (also known as the “Iroquois Confederacy” or eventually the “Six Nations”). In 1720 these five were joined by a sixth tribe, the Tuscarora. The purpose of the Confederacy was to renounce mutual warfare, while presenting a united front against outside raiders.

The tribal-military organization of the Haudenosaunee foreshadowed the eventual appearance, with the coming of class society, of the state. But as yet this state did not exist: there was no separate, permanent machinery of “bodies of armed men and prisons” characteristic of class society. Rather, the war chiefs held office only for the duration of warfare; the military force was the armed community instead of a separate standing army. Communal property also still prevailed.

Only in one area at the time of the arrival of Europeans was this communistic society beginning to break up and give way to a class social structure based on slavery: on the Pacific Coast. This was due to the extraordinary level of productivity of the main economic activity for Pacific Indigenous peoples: fishing. Production of a regular surplus means that it is possible for part of the community to live in idleness at the expense of the labour of others. Prisoners taken in war, instead of being adopted into the tribe as equals where all had to work (as was the case with the Haudenosaunee), now became slaves, objects of property and the chieftains, the men of property, became slave-owners. Along with this shift toward private property and class stratification came the shift toward a patrilineal and patriarchal organization of society.

Thus it is very clear that while communistic hunter-gathering was a prevailing form of economic and social organization prior to colonization, this was not the case everywhere. On the contrary, different Indigenous peoples from coast to coast were innovating, evolving, developing and seeing profound changes to their social and economic structures. This natural and vibrant evolution was cut short by European conquest, which disrupted the development of communal tribal society and sought to violently impose capitalist social relations.

The rise of European capitalism as the driving force for colonization

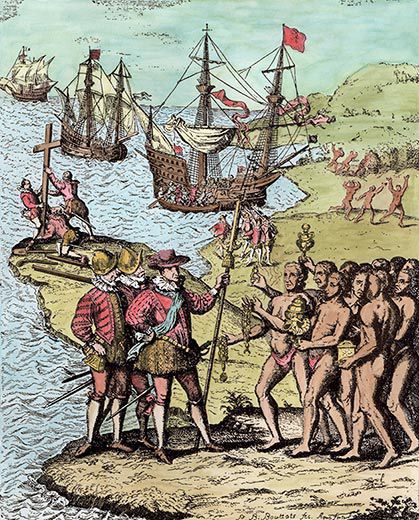

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels explained that the colonization of the Americas was integral to the development of capitalism through the forging of the world market. This was essential in capitalism replacing feudalism as the dominant mode of production and exchange in Europe. We can trace the beginning of colonization of what is now Canada to 1497 and onward, when there were several small expeditions from England, Portugal and France to the east coast. These nations were challenging the dominance of Spain, which had already begun colonizing the Caribbean in 1492 before going on to reap a harvest of gold and silver through the plunder and enslavement of the Indigenous people of what are now Peru and Mexico in the early 16th century. These expeditions were mainly backed by rich merchants, part of the ascendent capitalist class looking for goods to sell in European markets. This was the true driving force behind colonization.

The legacy of European colonization is truly horrific. It is estimated that between 1492 and 1900 that there were approximately 175 million excess Indigenous deaths in the Americas, with a 95 per cent reduction in population during that period. Historian David Stannard at the University of Hawaii has called this mass death of Indigenous peoples “the worst human holocaust that the world had ever witnessed,” and it is hard to argue with him. This is another aspect of what Marx was referring to when he said that capital comes into the world “dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

Theories of racial inferiority were developed during the formative period of capitalism in order to justify colonization. The church played a fundamental role in this process due to the divine authority which they were seen to have. Armies of pulpit propagandists were enlisted by stock companies to justify the merciless exploitation they would inflict upon Indigenous peoples. Their use of clergy for this purpose went as high as the Pope, who provided the legal and ideological framework for colonization through the Doctrine of Discovery in the 15th century. The doctrine asserted that any lands not inhabited by Christians were terra nullius, or “nobody’s land”, and were therefore available to be discovered and claimed.

The French were the first to push inland and established several outposts and settlements along the St. Lawrence River valley from the 1600s onwards, marking the beginning of the French fur trade empire. The Company of New France was chartered in 1627 and given a monopoly by the French Crown to manage the fur trade in the colonies of New France, in return for being responsible for settling new French Catholics in the colonies.

While the Spanish and Portuguese built their empires to the south on conquest and slavery, and the British colonists massacred Indigenous peoples to take their land, the French were never powerful enough to take the same approach in North America. Instead, French colonial policy was based on making alliances with Indigenous tribes they came into contact with.

However, their colonial practices were no more virtuous than other European colonizers. The French held an extremely paternalistic and derogatory view of the First Nations they made alliances with, viewing them as “savages” that needed to be “civilized”. The relationship between the First Nations fur trappers and the French traders was also one of exploitation, with the Indigenous locals being the ones to trek for miles and hunt animals for fur while the traders reaped the profits.

The French also used a divide-and-rule tactic and fanned the flames of fratricidal wars to make those they traded with even more dependent on them. While some of these conflicts were long-standing, European intervention transformed what had once been sporadic, local contests waged with bows and arrows into bloodier wars of mutual extermination with firearms which extended over vast territories.

The scope of these wars was directly connected to the manipulation and forced integration of Indigenous peoples into the developing capitalist world market. As Indigenous tribes became more and more dependent on fur trading with the colonial powers, conflicts over hunting and trapping grounds developed into deadly wars with entire tribes being wiped out. The series of military conflicts that lasted for decades throughout the 17th century are popularly known as the “Beaver Wars”, which in and of itself demonstrates that this was essentially a battle over very profitable capitalist markets.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy refused to be made into a dependent “ally” of the French and were at war with them and their First Nations allies, the Huron-Wendat and the Algonquin, between 1640 and the 1660s. At one point the Haudenosaunee even seized Montreal and several key French outposts. While this resistance was eventually crushed by direct military intervention from France, it served to significantly weaken the colony. Unable to deal with ongoing conflicts with local First Nations as well as discontent from French settlers, the Company of New France surrendered its charter in 1663, making way for the British Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) to become the dominant force in the fur trade.

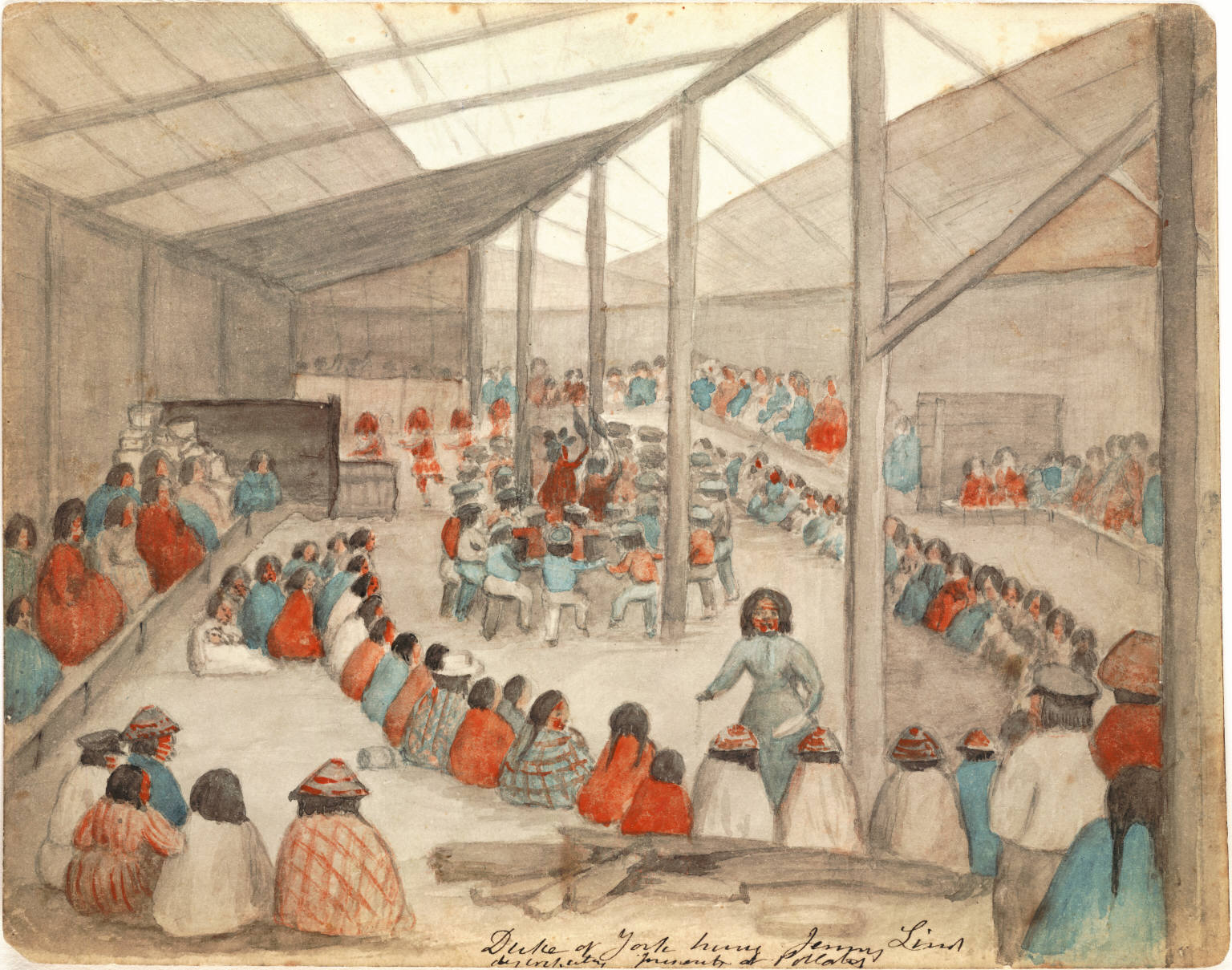

(Library & Archives Canada)

Another factor that weakened the French colony was continual war between Britain and France between the 1680s and 1750s, always pitting the colonies against each other. By the mid-18th century, Britain had laid the foundation for her industrial revolution and was emerging as a world capitalist power, while France remained fettered by feudal relations. This disparity was reflected in the colonies with the relatively low level of economic development in New France compared to the British colonies.

After the Seven Years’ War from 1756 to 1763, the British took over areas previously administered by the French. While the French had strategically made deals with Indigenous peoples in order to form alliances, the British approach was to treat them as a conquered people. This attitude was most graphically illustrated under British General Jeffrey Amherst, who thought that with the French out of the way, Indigenous peoples would be forced to accept British rule. Amherst took a hostile stance to Indigenous peoples and, especially after the Cherokee rebelled against the British in 1758, he started to restrict access to firearms and gunpowder for Indigenous peoples. In February 1761, in what was known as Amherst’s Decree, he ended the tradition of giving gunpowder and shot to chiefs as a diplomatic gesture of goodwill. This contributed to deteriorating relations between the Indigenous peoples and the British.

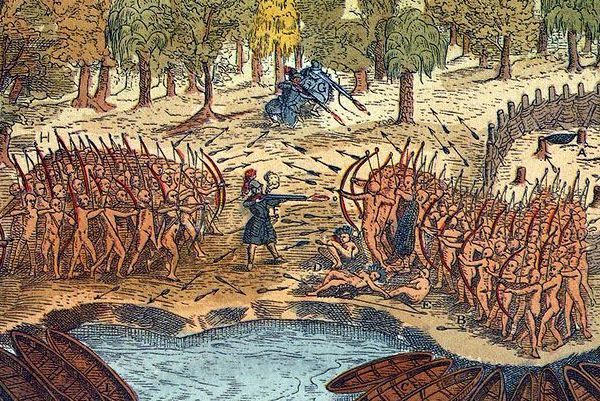

The British also refused to withdraw from areas west of the Allegheny Mountains, essentially occupying Indigenous land in the Ohio and Allegheny valleys. British generals were known for treating Indigenous people no differently than wild animals, following the lead given by Amherst. This enraged Indigenous peoples who banded together, waging a heroic war against the British colonial forces in 1763. More than a dozen Indigenous tribes, comprising thousands of warriors, united to drive the British colonizers from their land. This war became known as “Pontiac’s War” after the influential Odawa warrior who was one of the principal leaders of the Indigenous forces. This loose alliance of tribes destroyed eight forts, killing thousands of British soldiers and colonists and driving thousands more from their land.

While official accounts invariably speak of the brutality of the Indigenous peoples, the moral hypocrisy of the British colonizers is clear. Indigenous peoples were fighting back against an alien colonial force that was seeking to exterminate and replace them using the most underhanded methods. The latter’s brutal outlook was most graphically illustrated by Jeffrey Amherst himself, who argued for biological warfare saying: “Could it not be contrived to send the smallpox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.”

While the Indigenous tribes did not succeed in expelling the British, one of the results of this war was the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which stated that the Crown must negotiate and sign treaties with Indigenous people before land could be ceded to the colonies. The proclamation explicitly recognized that Aboriginal title to the land existed and that all lands would be considered Indigenous lands until ceded by treaty.

However, the purpose of the proclamation was not to protect Aboriginal title or rights. It was more of a cynical manoeuvre with the aim of restricting the growing power and independence of the American colonies, and was designed to guarantee the dominance of the British Crown by maintaining the state monopoly of ownership over the land.

According to the proclamation, only the Crown could acquire land from Indigenous peoples. The settlers were explicitly forbidden from claiming Indigenous land directly—it first had to be acquired by the Crown and then sold to the settlers. The whole idea was that the Crown was asserting its right to profit from and be the dominant force in the colonization and destruction of Indigenous peoples.

With France out of the way, the British Crown focused its efforts on curtailing the power of the nascent colonial bourgeoisie. This intensified conflicts which ultimately led to the American Revolution in 1765. Once again, the fate of Indigenous peoples was considered small change by the big powers, with each side making empty promises to enlist Indigenous allies.

The British Crown went on to break a number of promises to First Nations people and settled or sold unceded territories. For example, in return for fighting with the British against the Americans in the Revolutionary War, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy was promised the land lying six miles on each side of the Grand River which empties into Lake Erie. However, land grants were not upheld by the newly established Assembly of Upper Canada, and the Indigenous people of the Confederacy ended up with one fifteenth of the land previously promised. The settlement of Upper Canada was then carried out through a massive eviction of the First Nations people dwelling there.

With the Americans decisively defeating the British in the early 1780s, the American bourgeoisie adopted an even more aggressive policy than the British, expanding westward and disregarding any previous agreements the British had made with Indigenous peoples. Once again, Indigenous tribes united in what is known as the Northwest Indian War, fighting bravely and defeating the invaders on multiple occasions. Most notably at the Battle of the Wabash, an Indigenous army of Miami, Shawnee, Potawatomi and Lenape banded together and delivered the most decisive defeat ever suffered by the American military. They nearly wiped out the entire American force of 1,000 soldiers while suffering only minimal losses.

Indigenous peoples fought bravely against the colonizers on many occasions. In spite of this heroism, they were doomed to defeat in the long run. This is because at the end of the day, all other things being equal, the socioeconomic system with the higher productivity of labour will be victorious in any armed conflict. The American Revolution, which laid the political basis for unfettered capitalism based on industrial production, unleashed a development of the productive forces almost unparalleled in history. Confronted with this, the relatively underdeveloped economy of the Indigenous peoples, which had already been significantly distorted and weakened via the fur trade, did not stand a chance—in spite of the heroism and the desire to fight back. Indigenous chiefs obviously knew this fundamental truth as they forged alliances with the British against the Americans, in spite of the horrible track record of the British Empire.

During the War of 1812, First Nations support for the British against the Americans was again rewarded with betrayal. More than 10,000 First Nations warriors from the Great Lakes region and the St. Lawrence Valley participated in nearly every major battle. In exchange, Britain promised the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh a neutral Indigenous territory between the United States of America and British North America. But once the war was over, this promise was conveniently forgotten. After fighting in the war, First Nations were denied any recognition as parties to the peace, or as independent and sovereign peoples.

More thefts and betrayals

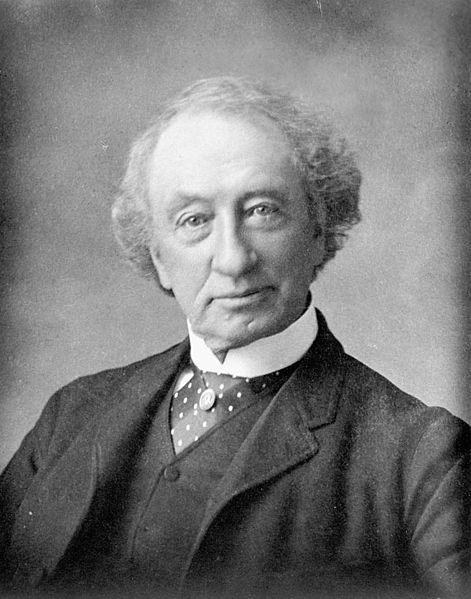

The birth of Canada in 1867 coincided with an historic theft of Indigenous territory. Having gained legal sovereignty over the vast West and North, encompassing eight million square kilometers, the Hudson’s Bay Company later sold these territories to the newly confederated Canadian state for £300,000 plus permission to retain 50,000 acres around the various trading posts. Unsurprisingly, the Indigenous people never saw a penny of this wealth and were never consulted. Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, commented that the people living on this land were handed over “like a flock of sheep.” The company had simply sold the Crown stolen, unceded land.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had made £20 million in the fur trade (worth approximately £1.5 billion today). A large portion of this was sent back to England and invested in industry there, providing much of the basis for spurring on the Industrial Revolution which made Britain a major world capitalist power. However, a significant amount of this wealth would be reinvested in the other colonies and Canada as well.

The HBC would also use alcohol in the oppression and exploitation of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Alcohol was a high-profit item that was often consumed at trading outposts. This ultimately limited the purchasing power of Indigenous people and had the effect of undermining traditional community relations. Indigenous chiefs and elders resisted this detrimental trade, while HBC protected its monopoly on alcohol sales and profited massively. Alcohol was used to keep Indigenous people dependent. HBC traders often showed up with quantities of alcohol at peak hunting times in order to literally steal furs from intoxicated Indigenous traders. The use of alcohol in the fur trade profited HBC greatly, with social consequences which are still felt to this day.

With enormous profits from the fur trade and alcohol monopolies as well as the sale of stolen land, the Hudson’s Bay Company was essential in the formation of the Canadian bourgeoisie and capitalism in Canada. In fact, HBC was the starting point for the development of the big bourgeoisie in Canada in terms of land development, the railways, shipping and banking. Thus it is clear that the exploitation of Indigenous peoples was key to the development of Canadian capitalism, and provided the necessary basis for the formation of the nascent Canadian bourgeoisie.

Canadian capitalism built on the subjugation of Indigenous peoples

By the time of Confederation in 1867, the disappearance of fur-bearing animals and the development of industry and trade had brought about the end of the fur trade (except for some parts of the north). This led the new capitalist class to direct more attention to other resources in Canada and to establishing a home market. Capitalism in Canada now required land development to promote capitalist agricultural production and the development of industry and trade around the extraction of raw resources. These economic demands created the need for a pool of cheap labour, something the Canadian bourgeoisie generally lacked.

While the Hudson’s Bay Company had previously benefited from keeping Indigenous people nomadic and engaged in hunting and trapping rather than pushing them onto reserves, that policy now changed. Treaties were established between First Nations and the Crown to clear land for capitalist development and exploitation. Practices aimed at “civilizing the Indian” were established to break traditional forms of governance and communal property. The economic base of Indigenous society had been effectively eradicated through capitalist exploitation. For example, bison herds were all but gone by the 1880s, as the skins and hides of the bison were perfect for use as belts and other parts of the machinery used in the developing industry in central Canada and the east coast of the United States. Now the cultural elements of Indigenous society had to be destroyed as well. This is because the primitive communist mode of production and its corresponding family form were incompatible with the development of capitalism and had to be destroyed from the perspective of the capitalist class.

While Indigenous peoples viewed the land and natural resources as collective property, their very habitance on it was a barrier to capitalist development. Furthermore, the capitalist class required a pool of pliable labourers, disconnected from their traditional land and collective means of survival such as hunting, who could be exploited for profit. They also needed to destroy Indigenous culture and ways of life in order to assimilate Indigenous peoples into capitalist society and minimize any resistance. The acquisition and theft of Indigenous lands played an essential role in the primitive accumulation of capital in North America.

Beginning in 1828, a series of government reports, including the Darling Report, targeted agriculture as a means of forcing Indigenous people down the road to “civilization.” The idea was to confine Indigenous people on reserves, where they would learn to cultivate the land, become “good Christians” with the selfless help of the church, discover the virtues of individualism, and eventually become a malleable workforce. In this way they would establish permanent settlements, abandon hunting and develop subsistence agriculture, thereby ceasing to be an obstacle to the development of the land.

As part of this policy, Indigenous peoples, particularly in the West, were confined to reserves where they were forced to cultivate the land. However, the land set aside for them to farm remained the property of the Crown, and was often of poor quality. Nevertheless, many Indigenous farmers had some success in the 1880s, thanks to new farming techniques and the collective organization of the work. For example, in 1890, two farms on reserves in Prince Albert and Regina won the first prize in a wheat competition.

Faced with this prosperity, and under the pressure of white farmers who complained about competition from Indigenous farmers, the federal government adopted a series of measures to limit the development of Indigenous agriculture. Officially, these measures were taken on the pretext that Indigenous farmers should start by learning subsistence farming before moving on to commercial farming.

In 1881, the sale of agricultural products by Indignous people was restricted. Hayter Reed, the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs, was responsible for the implementation of the Peasant Farming Policy in 1889, which hindered developing Indigenous agriculture. Reed was of the opinion that it was better for Indigenous people to learn to cultivate small plots of land than to engage in larger-scale commercial agriculture. Accordingly, this would restrict farming land and eliminate the need for labour-saving machinery. Reed argued that the peasants of other countries had farmed successfully for centuries with ancient hand tools and he thought that Indigenous people had to learn to use these tools and thereby advance through the historical stages of agricultural technique before being allowed to compete with white farmers. He forbade Indigenous people from purchasing agricultural machinery, and forced Indigenous farmers to use archaic hand tools.

With the implementation of the Peasant Farming Policy, Indigenous farmland was divided and allocated individually into 40-acre parcels of land to encourage individualism and private property and to undermine the collective spirit and sense of community. Once the parcels were distributed, the “unused” lands were then sold, thereby further reducing the size of the reserves.

Unfair treaties and the Indian Act

Treaties played an important role in preparing the land and Indigenous people for capitalist development. The legal basis for treaties was twofold: the British North America Act, which gave the Crown authority to deal with Indigenous people, and the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which stated that all legal title to land rests with the Indigenous peoples unless formally extinguished via treaty. This proclamation is the legal basis for the Aboriginal land title claims which Indigenous people use in their struggle to the present day. However, as previously mentioned, the Royal Proclamation was never intended to defend Indigenous land rights, but to prevent the colonies from acquiring land directly in order to ensure a monopoly on land for the British Crown. Much manipulation and misrepresentation was used during treaty negotiations to defraud Indigenous people from large swaths of their land and push them onto non-arable and lower-quality land.

The purpose of the treaties for the Canadian state was expressed by Indian Commissioner J. Provencher in 1873: “There are two modes wherein the Government may treat the Indian nations who inhabit this territory. Treaties may be made with them simply with a view to the extinction of their rights, by agreeing to pay them a sum, and afterwards abandon them to themselves. On the other side, they may be instructed, civilised and led to a mode of life more in conformity with the new position of this country.”

First Nations peoples entered such unequal agreements because they were under great pressure: the death toll from smallpox and other epidemic diseases was very high; several animals that were traditionally hunted for survival had gone extinct; and the Indigenous people in the United States had been brutally massacred. On the Prairies, railroad surveyors were at work laying out the right-of-way for the Canadian Pacific Railway and the state was preparing to forcefully clear First Nations and Métis people in the way of the development.

In 1871, after Canada assumed control in Red River, the Crown opened negotiations with First Nations for rights to the land, as per the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which was included in the articles of Confederation. Known as the “Numbered Treaties” or the “Post-Confederation Treaties,” this era of treaty-making ended in 1921 and began on the Prairies. It also included parts of the north and some regions in western Ontario. While First Nations in some regions of B.C. were included, this was not the case for the majority in the province who were not part of this treaty process.

During the first period of negotiations between 1871 and 1877, some First Nations negotiated and won important concessions based on the bitter experience of people who had signed treaties earlier in the process. For example, the terms of Treaty 6 included provisions that had not been negotiated in Treaties 1 to 5 such as the presence of a medicine chest to be kept at the house of the Indian agent on reserves, measures to protect from famine and disease, more agricultural supplies and the provision of education on the reserve.

That the chiefs signed the treaties should not be taken as an indication they were happy to do so, and serious protests by chiefs like Poundmaker at the signing of Treaty 6 were made. Rather, to the First Nations whose leaders agreed to the treaties, they were seen as a matter of necessity resulting from the loss of the economic foundation of their way of life.

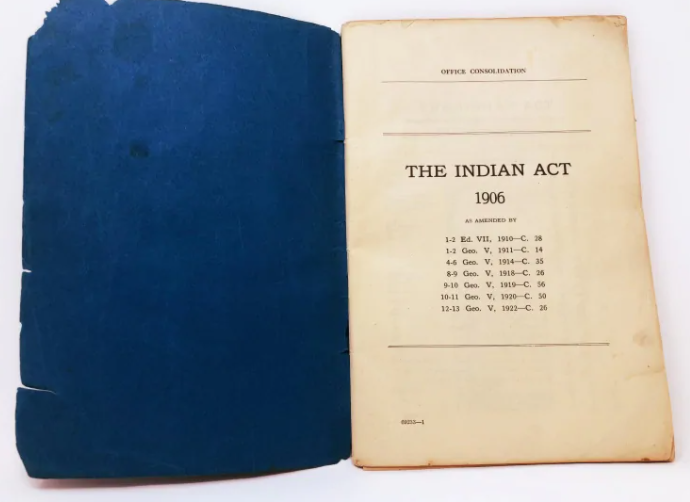

By the time of Confederation, all the basic features of Canadian policy towards Indigenous peoples were in place, but they were scattered over a series of statutes and lacked a consolidated administrative structure. With Confederation, control over all “Indian affairs” was assumed by the federal government. Statutory consolidation occurred with the Indian Act of 1876.

The Canadian bourgeoisie’s plan to convert Indigenous people on reserves into a cheap source of labour and source of agricultural surplus had largely failed up to this point. The Indian Act was an attempt to solve this problem and put Indigenous people on reserves under a system of land tenure to ensure control of on-reserve agricultural production.

The state had total control of the land, and hence the lives of people living on reserves. The state decided everything from what crops to sow to harvest time. It provided all the equipment and determined sales and prices. The income from sales went to the Department of Indian Affairs, supposedly to be spent on improvements on the reserves. In practice, Indian Affairs was a backwater department, with little supervision from Ottawa. According to author Heather Robertson, millions of dollars were misappropriated and misused in this way. Thus, in a certain sense the Indigenous people on reserves became agricultural labourers who worked for Indian Affairs. In this way the reserves indeed became a source of cheap labour as Indigenous people on reserves became employees of the state.

The Indian Act gave the new Canadian state sweeping powers over all aspects of the lives of First Nations people, including the legal authority to replace traditional forms of Indigenous governance, to forcibly relocate reserve land, to dictate criteria for Indian status and to ban spiritual and cultural practices. In place of traditional forms of governance, the band council system was imposed. The reserve and residential school systems were also introduced under the Act, which gave the federal government the power to expropriate reserve areas supposedly for the development of infrastructure and other public works.

The Indian Act forbade First Nations people from speaking their language and practicing their traditional religions. It forbade First Nations people from appearing in public in traditional dress and banned the potlatch in British Columbia and the Sun Dance in Alberta. The aim was to break up traditional ways of life to turn Indigenous people into a capitalist workforce as well as to clear land for capitalist development, such as the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The intent of this Act (which still remains in place today, having been amended several times but retaining its original purpose), was to subjugate and forcibly assimilate Indigenous people into bourgeois society in order to remove them as a barrier to the development of the land, resources, and capitalism in general. The whole idea behind the Act was to try to force Indigenous people to renounce their Indian status and assimilate into bourgeois society. In the time-honoured tradition of bureaucratic doublespeak, this process of forced assimilation was legally referred to as “enfranchisement”.

Under the Act a whole series of measures were adopted to this end, including provisions to destroy the matrilineal nature of many First Nations cultures. Other measures were designed to enforce “enfranchisement”. For example, any First Nations people admitted to a university were forced to renounce their status.

The Act also contained a series of political measures designed to politically control Indigenous peoples. The Act forbade the formation of political organizations by First Nations people and denied them the right to vote. Until 1960 First Nations people could vote in federal elections only if they renounced their status. The Act prohibited anyone (both First Nation and non-First Nation people) from raising funds for First Nations legal claims without a special license from the superintendent general of Indian Affairs. This move was designed to prevent First Nations from pursuing land claims.

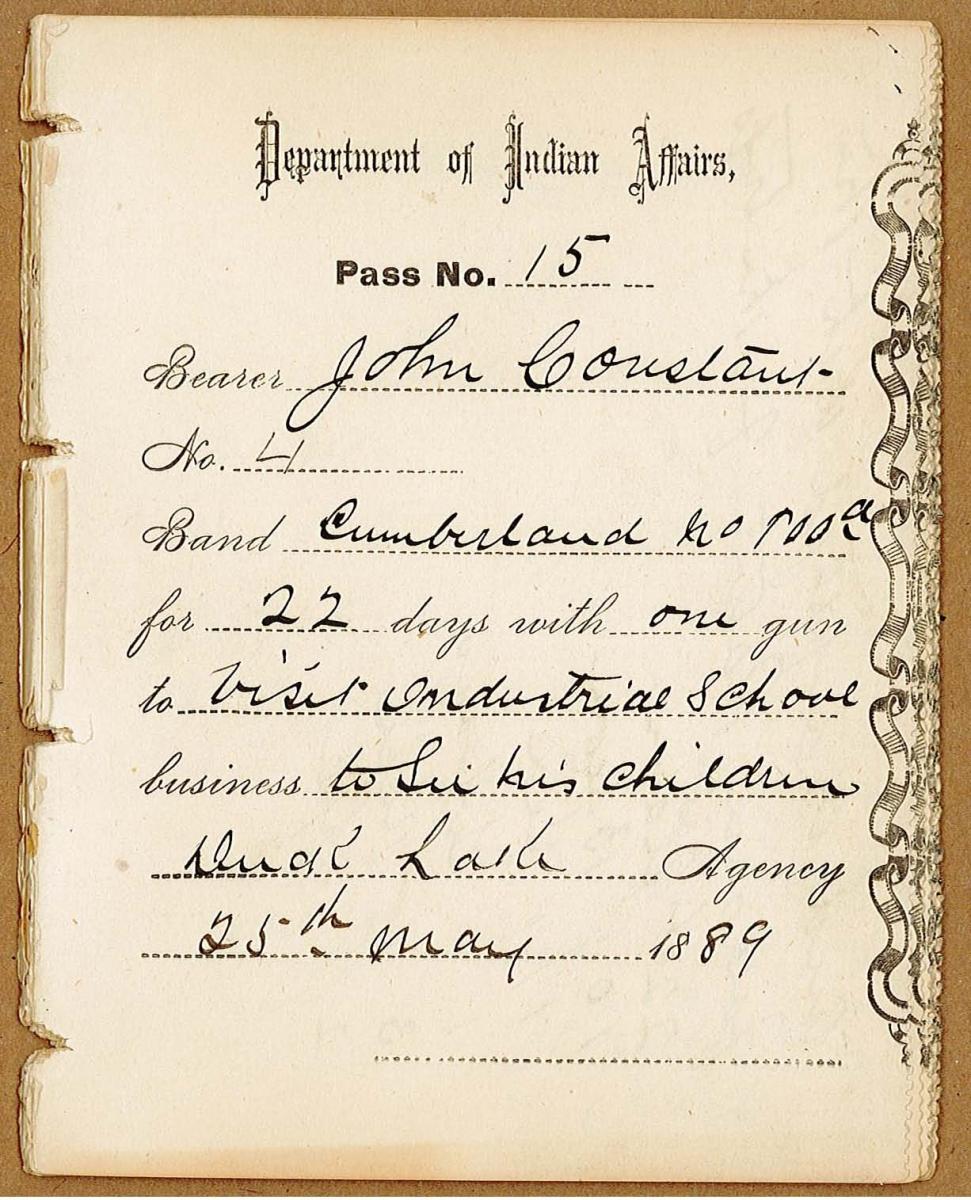

From 1885 until the 1940s a pass system was in place to control the movements of First Nations people and keep them on reserves. First Nations people living on reserves were forced to obtain permission in writing from an Indian agent if they wanted to leave the reserve. If caught off reserves without one of these passes, they were either incarcerated or forcibly returned to the reserve. This policy was put in place with the outbreak of the North-West Rebellion and was designed to prevent the spreading of insurrection.

The Riel Rebellions and their aftermath

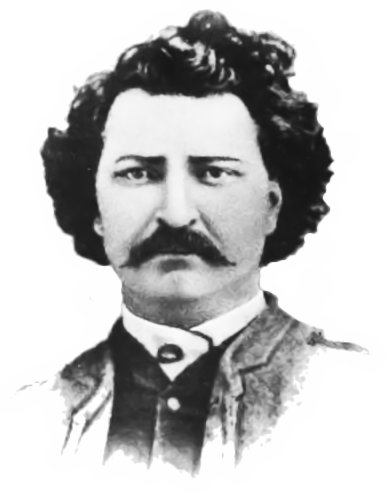

Perhaps the most important episodes of resistance to the seizure of First Nations and Métis lands are the Red River Rebellion of 1869-1870 and the North-West Rebellion of 1885, both associated with the name of the great martyr, Louis Riel.

The Métis Nation is a culturally distinct Indigenous group whose origins began with the children of various European and Indigenous peoples. The Métis Nation is geographically diverse but maintains unique culture, traditions, languages (like Michif and Bungee), way of life, collective consciousness and nationhood.

The Red River settlement, located in today’s Manitoba, was inhabited by just over 10,000 people in 1871, mostly Métis with almost an equal number of francophones and anglophones. The settlement was founded by Scottish settlers in 1812, but was dominated by the HBC, which had possessed the fishing and hunting rights throughout all of Rupert’s Land since 1670—although the land belonged to First Nations and Métis. In 1836, the control of the colony was formally surrendered to the HBC, which they ruled from 1836 to 1869.

However, the British imperialists and Canadian colonial state feared that if nothing was done, especially with the pressure from the United States, the territory of Rupert’s Land would be annexed by the United States. Moreover, the interests of developing Canadian capitalism (and also the interests of the Crown) demanded that the country be linked from coast to coast. The Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada resolved that, “In view of the speedy opening up of the territories now occupied by the Hudson’s Bay Company, and of the development and settlement of the vast regions between Canada and the Pacific Ocean, it is essential in the interests of the Empire at large, that a highway extending from the Atlantic Ocean westward should exist, which should at once place the whole British possessions in America within the ready access and easy protection of Great Britain…”

At root, the driving force of this conflict was a change in the material relations of production. As Howard Adams explains: “the trouble was the conflict between two different economic systems—the old economic system represented by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the new industrial system.” He continues: “The clash of these two economic systems fueled the hostilities of 1869-70 in the Northwest, which resulted in Rupert’s Land being brought under the constitutional authority of the government in Ottawa, the seat of the industrial empire.”

At the top, the rulers of the HBC simply changed seats, with principal shareholder Donald A. Smith transferring his capital to railways, banks and other industries. John A. Macdonald’s government was filled with former HBC directors like Smith, who recommended annexing the North-Western Territory so they could expand their own industrial empire and build a capitalist nation state. Matters were, however, somewhat different for the people living in this vast territory who now had their land and entire way of life threatened.

The Rupert’s Land Act of 1868 authorised the land transfer and the deal was signed and became effective on July 15, 1870, with the stipulation that treaties would be signed with Indigenous nations. At the time Métis were not legally recognized as an Indigenous people by the Canadian government, and not included in the “Indian Act” or assumed to be covered by the provisions of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. It was not until 2003 in the landmark Powley decision that Métis received such acknowledgement. Naturally, in 1870, the HBC and the government negotiated without seeking the opinion of the Métis. This would fuel the anger of the Red River Métis.

(Library & Archives Canada)

As mentioned previously, HBC surrendered Rupert’s Land (which amounts to one-third of current Canadian territory) for £300,000 pounds ($1.5 million), which was a very cheap price at the time. The historian W.L. Morton says: “One of the greatest transfers of territory and sovereignty in history was conducted as a mere transaction in real estate”.

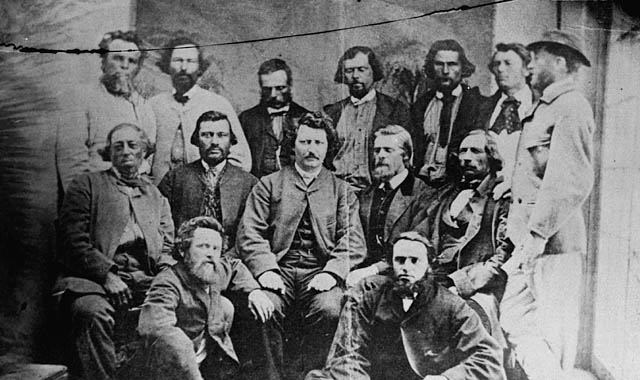

The transfer of territory was to be implemented on December 1, 1869. The Métis of Red River started to organize against this “annexation without consultation” in October that year by forming the Métis Committee, with John Bruce as president and Louis Riel as secretary. In November, Riel led a group of some 400 armed riders to seize Fort Garry, a strategic point in the settlement. The Red River Rebellion had begun.

In December, a provisional government was formed by the Métis, the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia, which drafted a list of terms for entry into Confederation. Faced with a revolutionary democratic movement, the Canadian government temporarily renounced taking control of the territory. The Métis, by revolutionary action, had established a bourgeois-democratic government and inflicted a humiliating blow on the Canadian ruling class and British imperialists. Interestingly, this was a united struggle of English and French Métis, where the linguistic rights of both groups were to be guaranteed by the new government.

The Métis issued a List of Rights to be presented to Ottawa. The Canadian state, while preparing to receive the delegates of the provisional government, was also preparing to repress the movement.

In May 1870, after negotiations between the provisional government and Ottawa, the Manitoba Act was passed, creating the province of Manitoba. However, in the following months troops were sent to re-exert the authority of the federal government, suppress the provisional government, and crush the rebellion. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald said in a letter that, “should these miserable half-breeds not disband, they must be put down.” In August 1870, British and Canadian troops arrived at Fort Garry to take control. Riel, rightly fearing that he would be lynched, escaped to the United States.

This is an example of the typical behaviour of the Canadian ruling class towards First Nations and Métis people since day one—a mix of feigned conciliation and repression. In a similar fashion, Justin Trudeau today can talk about “reconciliation” at the same time as the RCMP is sent to repress the Wet’suwet’en in British Columbia. In this manner, Trudeau is simply continuing the same policy the Canadian ruling class has pursued for centuries.

The Canadian ruling class was able to put down the Red River Rebellion and move ahead with the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. While a transcontinental railway was a condition of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation, this was also a lucrative endeavour for which there was intense competition among the ruling class. That is to say, it all boiled down to profit in the end. In 1872, shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan was granted the contract. It was soon discovered that he had donated $350,000 to the Conservative Party before being awarded the contract, forcing Macdonald’s government to resign in 1873 (he would return to power in 1878).

To protect profits, John A. Macdonald deliberately starved thousands of Indigenous people to clear a path for the Canadian Pacific Railway and open up the Prairies to white settlement. He ordered officials in the Department of Indian Affairs in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan to withhold food rations from First Nations until they moved to federally designated reserves far off the path of the railway. The First Nations were faced with starvation and were trapped on reserves from which they could not leave without the permission of a government Indian agent. Living conditions on the reserves were abysmal. But if the Indigenous people forced onto them complained about food rations, which were already substandard, they would find that their rations would be cut even further.

Historical records show that this practice was an explicit directive from Macdonald to federal officials. There are also public records of Macdonald bragging about keeping the Indigenous population “on the verge of starvation” in order to save government funds. One Canadian historian, James Daschuk, tracked a food shipment contaminated with tuberculosis which had resulted in a deadly outbreak back to an American company in which a senior official in the Canadian state had a major financial stake. Daschuk concluded, “the uncomfortable truth is that modern Canada is founded upon ethnic cleansing and genocide.”

However, the crushing of Indigenous peoples in the pursuit of profits was not achieved without a fight. Both the Métis and the Indigenous groups of the West put up a courageous fight against the Canadian state, notably again during the North-West Rebellion of 1885.

The origins of the North-West Rebellion can be traced back to the defeat of the 1869-70 Red River Rebellion. With the Manitoba Act of 1870, the Canadian government had promised to give 1.4 million acres of land to Métis families. However, bureaucratic delays slowed down the process and this measure was never implemented fully. In addition, settlers coming from the East were allowed land even before the Métis, which showed that the government had a heavy bias against the Métis. Two-thirds of the Métis, frustrated by the broken promises of the Canadian state, fled the province, with most of them moving westward and establishing settlements in what today is Saskatchewan.

With the development of agriculture and the advance of the Canadian Pacific Railway, there was a steady decline in the buffalo population. The Métis felt that their traditional semi-nomadic culture based on buffalo hunting was threatened, and they sent a petition to the government in 1874 for action to be taken, but to no avail. There were similar grievances coming from various Indigenous groups. The Canadian government, however, wanted to force the Indigenous population to abandon their nomadic life and establish themselves in villages based on agriculture. The Indigenous peoples on the reserves saw their food rations cut in 1883, which naturally added to the anger and discontent.

The white settlers of the West also had their own grievances. They were promised a life of prosperity by moving west, which never came. Representatives of the Métis, the First Nations and the white settlers met in May 1884 to discuss how they should confront the federal government. They decided to ask Louis Riel to come back from his exile in the U.S. to help them in their struggle. On the basis of the unity of all the exploited classes and oppressed peoples of the West, there was great potential for a successful revolutionary movement against the Canadian state.

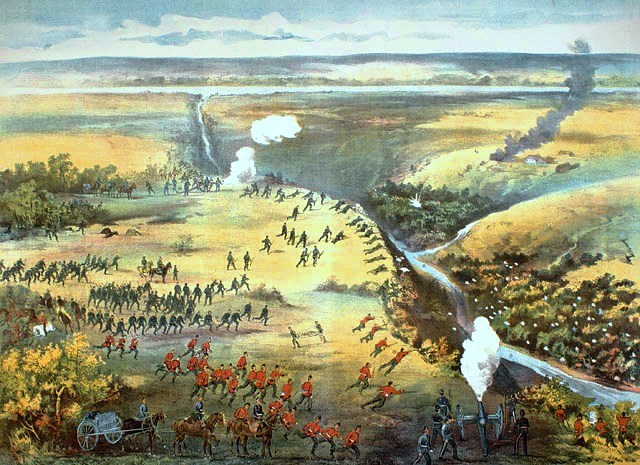

In December 1884, a petition was sent to the government with all the demands of the Métis, First Nations and white settlers. The government’s response was to set up a public inquiry to investigate the problems. This was seen as another empty gesture, and under the leadership of Riel, a new rebellion erupted. On March 18-19, an armed Métis group formed the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan with Riel as president. The rebellious Métis and First Nations scored a victory in a battle on March 25-26 against the North-West Mounted Police, the forerunner of the RCMP, which had been established in 1873 to maintain order in the West and crush Indigenous resistance.

This victory encouraged other First Nations to join the movement. However, the Canadian government wasted no time and quickly moved to regain control. No less than 5,000 men were sent by Ottawa to put down the rebellion. Racist hysteria was whipped up by the ruling class in the press with dire warnings about “Indian outrages” that needed to be stopped. This campaign succeeded somewhat in dividing the population and turning some of the white settlers against the armed struggle. On May 15, Riel surrendered and in June the rebellion was over.

It is revealing to note that the first war in history waged by Canadian troops without British soldiers assisting was here, in Canada, against the Métis and First Nations protesting and resisting mistreatment by the Canadian state. Once again we can see that the Canadian state and its coercive police apparatus are founded on the subjugation and violent suppression of Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty.

The subsequent trial of Riel caused massive division amongst the Canadian population. The fact that Riel was given a death sentence while the lives of other rebel prisoners were spared was a cynical political manoeuvre. In a classic divide-and-rule move, Macdonald, the Conservative prime minister, was seeking the support of the anglophone population at the expense of francophones and people in Quebec. Propaganda was spread claiming that Riel was a traitor. The trial was seen in Quebec for what it was: an example of the oppression of francophones by the Canadian state. The jury was entirely composed of anglophones. Macdonald infamously said about Riel, “He shall die though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour.”

And this is what happened. Louis Riel was hanged on November 16, 1885 in Regina. His execution caused an outpouring of anger in Quebec. A massive demonstration of 50,000 people was held on November 22 in Montreal, the biggest demonstration in the history of Quebec at the time. On November 27, six Cree and two Assiniboine warriors were also hanged.

From the bourgeois perspective, Louis Riel is today considered one of the most controversial figures of Canadian history. For our part, we are proud to consider Riel as part of our revolutionary heritage. His struggle to resist the Canadian state and for the rights of the oppressed Métis people is an inspiration for us today.

Residential schools: Tools of cultural genocide

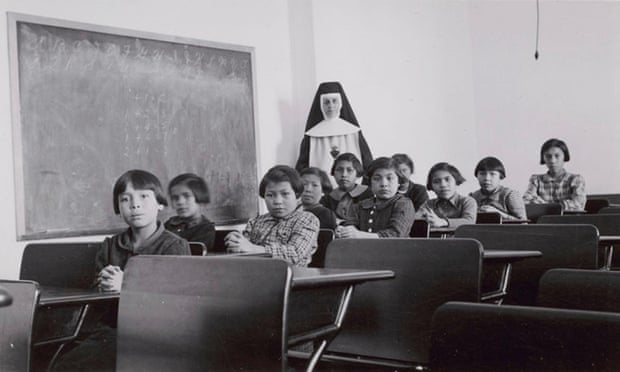

While genocidal and violent tactics were used in the face of resistance, the Canadian state’s preferred policy was still assimilation. This is because a pool of labourers was largely lacking in Canada. Canada never developed a large slave trade and settlement was insufficient to meet the needs of capitalist development. Therefore the capitalist class reasoned that the Indigenous people could be broken and assimilated to serve their needs. One of the main tools toward this end was the horrific residential school system.

Missionary schools run by the church had been in operation as early as the early 17th century in order to “civilize” Indigenous children by imposing the Christian faith on them. The new federal government began making small per-student grants to many of the church-run boarding schools in the 1880s and dramatically increased its involvement in residential schooling.

The purpose of the schools was not to educate, but to break Indigenous children’s link to their culture and identity. This is why the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) concluded in its 2015 report that the residential school system amounted to cultural genocide. The Canadian government pursued this policy of cultural genocide because it wished to relieve itself of its legal and financial obligations to Indigenous people and gain control over their land and resources. If every Indigenous person had been assimilated there would be no reserves, no treaties and no Indigenous rights. Furthermore, by breaking children’s link to their culture and traditions, the hope was to turn to them into malleable wage labourers upon graduation instead of relying on their traditional forms of survival. Even though the last residential school closed in the 1990s, breaking the link between Indigenous people and their culture, language and traditions is a continuing imperative for Canadian capitalism. This can be seen in the chronic underfunding of things like First Nations education, health care, and the intolerable conditions on reserves and amongst the urban poor.

From the 1870s until the last school closed in 1996, at least 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children attended residential schools in Canada. The Indian Act gave Indian Affairs the power to forcibly remove children from their homes; these children were essentially kidnapped. Inuit and Métis people are not governed by the Act, but at various points in time their children were enrolled in either federal schools or in provincial ones with similar intents and policies—often in partnership with the Church.

More than 130 government-funded, church-administered schools existed across the country, with the express purpose of “civilizing” Indigenous children—tearing families apart and leaving scars that continue to be passed on generationally. The conditions of the schools and the treatment of the students was horrific.

Spiritual and cultural practices were banned and the children were not allowed to speak their own languages. In a dehumanizing fashion they were referred to by numbers in many schools. Punishment of children for misbehaviour was often brutal and abusive. There are reports of children being lashed, beaten, having their heads shaved, being locked in small confinement cells for weeks at a time, given diets of water and bread, and having their pants pulled down and publicly shamed. Physical and sexual abuse was rampant.

At least 3,200 children who attended the schools never returned home. Records were regularly destroyed, suggesting that the actual number of students who died may have been far higher (between 1936 and 1944 alone, 200,000 Indian Affairs files were destroyed). Causes of death included disease (50 per cent tuberculosis), fires, and suicide, with many children dying of exposure while trying to escape. Poor health care and nutrition were the norm. Government and church officials were made aware of the problems many times and nothing was ever done to stop the abuse. This is because the abuse was both implicit and explicit in the design of the residential school system.

Returning home after years separated from their families and unable to speak the language of their elders, students became alienated from their traditional communities. They did not receive the nurturing care that children need to develop healthy relationships in their adult lives, leading to cycles of violence and mental health challenges passed down from generation to generation. This is what is known as intergenerational trauma, and its impacts on Indigenous communities have been devastating.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission traced a direct connection between the intergenerational trauma suffered by Indigenous families over the course of more than a century and social problems faced by Indigenous communities today such as poverty, homelessness, violence, high rates of health problems, incarceration, mental health challenges, and drug and alcohol addiction.

The White Paper

While the last residential school would not close until 1996, state policy shifted from the 1950s onwards towards what was termed “integration”. The 1951 amendments to the Indian Act emphasized measures for integrating services for First Nations peoples with services for all Canadians, including phasing them into the mainstream school system.

The final step in this policy of “integration” was introduced in 1969, when the federal government under Pierre Trudeau issued what became known as the White Paper and announced its intention to absolve itself of responsibility for Indigenous affairs through the repealing of the Indian Act.

In keeping with Trudeau’s vision of a “just society”, the federal government proposed repealing legislation it considered discriminatory. The Trudeau government viewed the Indian Act as discriminatory, not for example because it was the legislative framework that governed the destruction of Indigenous communities and genocide of Indigenous peoples, but because it applied only to Aboriginal peoples and not to Canadians in general. The Trudeau government thus proposed ending the special legal status of First Nations peoples and dismantling the Department of Indian Affairs in the name of “equality”.

The White Paper stated that removing the unique legal status established by the Indian Act would “enable the Indian people to be free—free to develop Indian cultures in an environment of legal, social and economic equality with other Canadians.” In addition to the elimination of Indian status for First Nations and the dissolution of the Department of Indian Affairs, the White Paper proposed transferring responsibility for Indigenous affairs to the provinces and integrating these services into those provided for the general population. The White Paper also proposed the privatization of reserve lands such that it could be sold by the band and/or its members.

There was significant opposition to the White Paper on the part of First Nations peoples. While many recognized the Indian Act as a racist and colonial piece of legislation, they did not want to lose the few rights they were guaranteed under it. Firstly, the White Paper had completely ignored the issues and concerns raised by Indigenous leaders during the consultation process for the paper. Many Indigenous peoples viewed the White Paper as the finishing stroke in the long-standing goal of the Canadian ruling class and state to assimilate Indigenous peoples into bourgeois society. Many correctly saw it as leading directly to cultural genocide and saw it as a crass attempt on the part of the federal government to “pass the buck” to the provinces. It was seen as an attempt by the Canadian government to absolve itself of responsibility for historical injustices.

The White Paper was considered a slap in the face by many Indigenous people. While many would have been happy to see the end of the Indian Act and the Department of Indian Affairs, and along with them centuries of oppression, many viewed the White Paper as an attempt on the part of the federal government to walk away from its obligations under various agreements and treaties. The lives of Indigenous peoples had been completely governed and dominated by these accords, and as oppressed peoples they were never in a position to simply walk away from them. They could not simply ignore the federal government or the terms of Indian Act, as these defined their very existence. For the federal government now to simply walk away from its historical obligations, all the while preaching “equality” and the privatization of reserve lands, was more than an insult.

Eliminating status for First Nations and transferring responsibility for Indigenous affairs to the provinces essentially amounted to placing reserves on an equal footing with municipalities under Canadian law. Many reserves, if not most, are not economically viable and could not compete with other municipalities for jobs and investment. The result would be an emptying out of the reserves as people left to find work in the cities. After centuries of economic strangulation of the reserves by the federal government, the White Paper—by now trying to equalize them with other municipalities while offering no legal or economic protection for reserve residents—was correctly seen by many Indigenous people as an attempt to destroy the reserves and force Indigenous people into the cities. This was in reality a type of Enclosure Act, and can only be understood as forced assimilation and genocide.

The White Paper also sparked a new era in political organizing in Indigenous communities. Harold Cardinal, a young Cree man who was head of the Indian Association of Alberta, responded to the White Paper with a book called The Unjust Society exposing the hypocrisy of Trudeau’s so-called “just society.” Cardinal stated openly that the White Paper was “a thinly disguised programme of extermination through assimilation” and viewed it as a form of cultural genocide. In 1970, the Indian Association of Alberta rejected the White Paper in a document called Citizens Plus, which is also known as the Red Paper. The Red Paper became a central position around which Indigenous opposition to the White Paper galvanized.

In British Columbia, the controversy over the White Paper sparked a new period of political organizing. In November 1969, three Indigenous leaders, Rose Charlie, Philip Paul, and Don Moses brought together 140 tribal leaders—the largest meeting of tribal leaders to that point. They met to develop a collective response to the White Paper and in turn founded the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs (UBCIC). The UBCIC issued its own rejection of the White Paper in a document called the “Brown Paper” which still forms a cornerstone of its current policy.

As a result of First Nations opposition, the White Paper was formally withdrawn in 1973. This had the effect of strengthening First Nations organizations across the country, particularly the National Indian Brotherhood, which would later form the Assembly of First Nations.

One of the first acts of a socialist government in Canada would be to repeal the Indian Act. Getting rid of this oppressive piece of colonial legislation would be one of the first steps towards ending centuries of oppression of Indigenous peoples. However, Indigenous people themselves must play the decisive role in this liberation from colonial oppression. A socialist government could not act unilaterally in this regard and must act in full unity with Indigenous peoples. In repealing the Indian Act, we would guarantee full rights to Indigenous peoples on and off reserves and work in unison with Indigenous peoples in developing a plan to end colonial oppression. Under socialism, the way forward will be determined by Indigenous peoples themselves, especially in relation to the Indian Act and the future of the reserve system. To be sure, it would be just as criminal and oppressive to force Indigenous people off reserves as it was to force them there in the first place.

From Red Power to today

In the context of the general societal radicalization of the 1960s and 1970s, there was also an upturn in the Indigenous movement. The White Paper only added fuel to the fire. The period of the late 1960s and early 1970s was a revolutionary era with mass movements and revolutions all over the world, and Indigenous people drew direct inspiration from many of these movements. The movement that developed in North America at the time was generally known as the Red Power movement. This movement was globally influenced by the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the U.S.

But the movement in general was far from homogenous. Like any struggle of an oppressed group, there were various approaches which ultimately stemmed from different class outlooks. At first, the movement was based on identity, centred around Indigenous unity for common cause against the “white man.” But many Indigenous leaders under the radicalization of events were pushed to the left, with a layer identifying with revolutionary Marxism. The need to broaden the struggle out to non-Indigenous people, and to link it to a broader fight against capitalism, were also being openly explored and debated.

A clear divide within the Indigenous movement was also exposed. The most well-known Indigenous Marxist, Howard Adams, was active fighting against a layer of petty-bourgeois Indigenous bureaucrats. He describes this in his best selling book Prison of Grass:

It is common practise of imperial governments to use middle-class native elites to provide support for their administration. Middle-class society, which shares the same value system and ideology as the ruling class, provides political stability for the capitalist system. Therefore, as soon as natives start action towards liberation, governments make serious efforts to bring native leaders into middle-class society. After these leaders are co-opted, they become supporters of the government and of the colonial rule that suppresses their people.

Adams describes how these “uncle tomahawks” were nurtured with the growth of government grants and reliance on white advisors who teach them to be subservient.

This layer of petty-bourgeois Indigenous bureaucrats acted as a brake on the movement. Against this trend, a young layer of Indigenous Marxists developed throughout the 1960s and helped to found rival organizations to push for more militant tactics. Métis activist Malcolm Norris was a Marxist and a founding member of the Métis Association of Alberta. His friend and collaborator James P. Brady was a member of the Communist Party of Canada. There is suspicion that Brady was assassinated for his political activities after he disappeared while out prospecting.

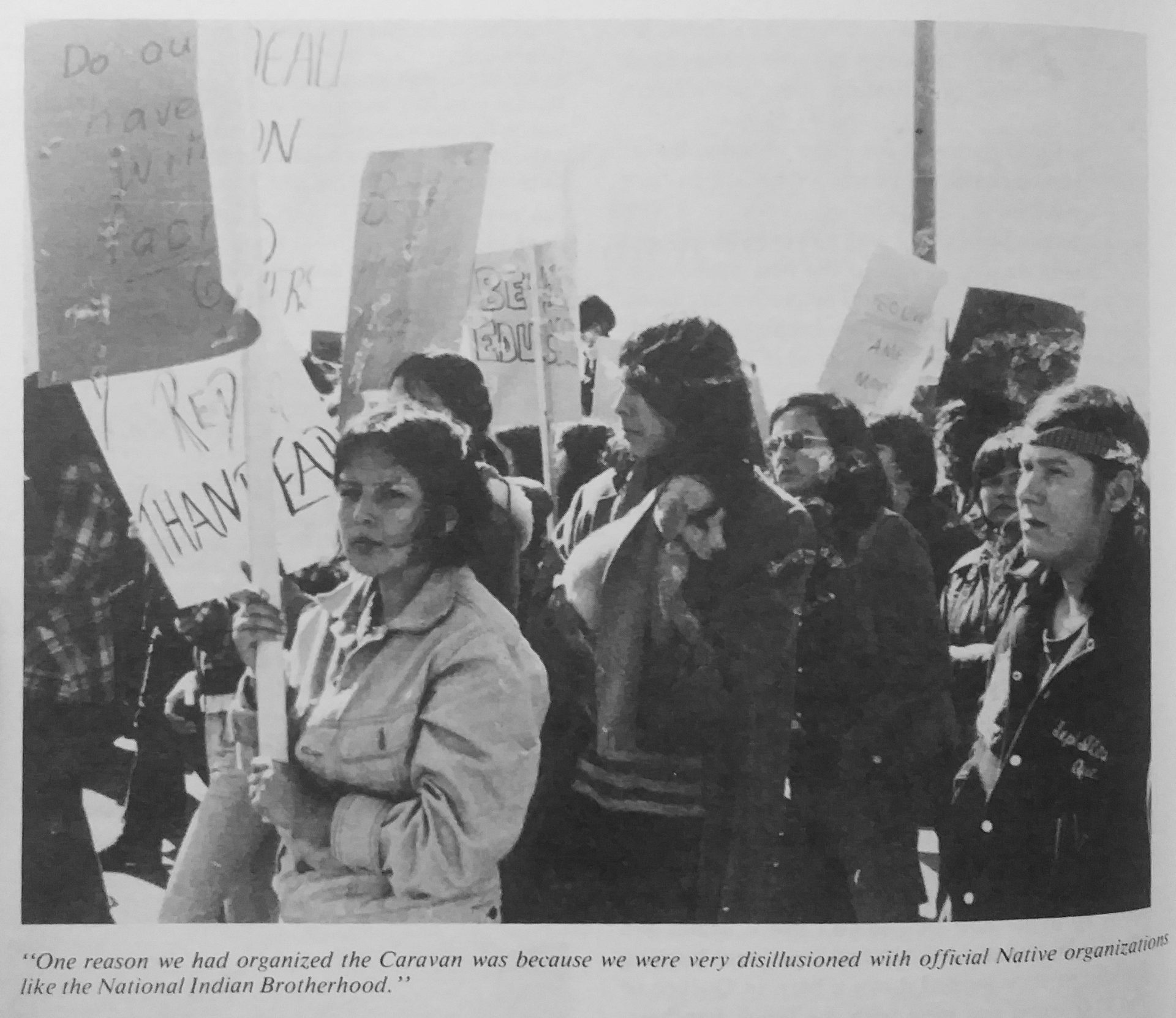

Many Métis and Indigenous militants drew openly revolutionary conclusions and sought to link up the Indigenous struggle with the rest of the working class in a fight for socialism. Cree activist Vern Harper, who was a leader of the movement in Ontario, said that “There’s a more militant and revolutionary theme emerging, which is beginning to get support from all elements of the native movement…Native and non-native people are seeing that capitalism doesn’t serve the masses. It only protects the capitalists’ interests…” Harper organized the Native People’s Caravan which traveled from Vancouver to Ottawa to “welcome” Trudeau’s re-election in 1974. This peaceful march was violently repressed by riot police. Just prior to this, Harper had run for the Marxist-Leninist Party in the federal riding of Toronto Centre.

There were a series of occupations of government and Indian Affairs offices across Canada at this time, complemented by several roadblocks. One of the key events was the occupation of Anicinabe Park in Kenora, Ontario in July 1974, where for the first time in this period arms were used by First Nations people to assert their rights and protect the occupation. This occupation, organized by the Objibway Warrior Society, lasted 39 days and involved a standoff between 100 First Nations participants and police, resulting in dozens of arrests. During these events, a wave of racism was whipped up, accompanied by claims that Indigenous militants were all communists. This was probably not so far from the truth.

The “uncle tomahawk” leaders of the main First Nations political bodies such as the National Indian Brotherhood and the provincial Indian associations spoke out against the action as condoning violence. Even leaders like Harold Cardinal recoiled when faced with the militancy of ranks in the movement. As the radical Indigenous movement subsided, these layers, free from the pressure of the mass movement, moderated even further, developing into a stable group of petty-bourgeois and bourgeois natives. Many of these people ironically moved into the orbit of the Liberal Party, as Cardinal himself did in 2000, running unsuccessfully on the Liberal Party ticket.

In the United States, this situation developed into a split in the American Indian Movement with a well-known AIM leader, Russell Means, resigning from a right-wing perspective. The AIM Grand Governing Council issued a declaration distancing the group from Means, criticizing him for going to Nicaragua to support the “Miskito Indians who were allied with the anti-revolutionary Contras,” as well as his “recent forays into conservative politics.” Means had joined the Libertarian Party and had famously criticized Marxism, saying that “Marxism is as alien to my culture as capitalism.”

Another debate emerged between some First Nations men and women. First Nations women were discriminated against under Sec. 12 (1) (b) of the Indian Act, whereby First Nations women who married non-First Nations men lost their status as registered Indians (whereas First Nations men who married non-First Nations women did not). Anishinaabe community worker Jeannette Corbiere Lavell took the case of discrimination up legally. In 1974 she went to the Supreme Court of Canada to challenge the Indian Act and lost the case, which led her to form the organization Indian Rights for Indian Women. This particular struggle was later won, at least formally according to bourgeois law, through Bill C-31 which was passed in 1985.