The summer of 2021 in British Columbia was one of the hottest ever on record, caused by a weather event known as a heat dome. This once-in-1,000-years weather event (made 150 times more likely by climate change), saw temperatures of up to 49.6 C in the province. This unbearable heat led to the deaths of hundreds of people in B.C. But these people did not die from the heat alone. Their deaths were preventable, and were facilitated by the inaction of the government, widespread unpreparedness, poor housing, and overstretched emergency services.

It’s estimated that if emissions continue to increase, the mean number of days above 30 C in Vancouver will nearly quintuple. Japan and the United Kingdom have gone through the worst heat waves in their recorded history. B.C. is also now going through another heat wave which, while not as bad as last year’s, will see temperatures of up to 40 C. This heat is the new norm, and it is imperative to learn from tragedies like the 2021 heat wave to adapt to this new reality.

A year after B.C.’s heat wave, a panel convened by the British Columbia Coroners Service released a report to review the deaths which followed last year’s extreme heat. The report states 619 people died from the heat, with more than half dying alone. Two-thirds (67 per cent) were over 70 years old. Ninety-eight per cent died indoors, with most not having adequate cooling systems like air conditioners (AC) or even fans. Deaths were concentrated in lower-income housing, and the lag of ambulances was a contributing factor. For almost 50 of the deaths, an ambulance took 30 or more minutes to arrive. Those who died were some of the most vulnerable people in the province. They died alone, without help, and would have lived had they simply been checked on and cooled down.

The report made three key recommendations to the province when dealing with similar heat waves. The first was the need for a “coordinated provincial heat alert response system,” largely meant to establish a plan and outline which agency has the responsibility to respond. This point comes from the fact that while the 2021 heat wave was forecast a week in advance, and the government was warned of the risks, little was done to prepare. The province’s emergency alert system was not used, forces weren’t mobilized to check on the vulnerable, and many were simply not made aware of the risks. At the time, one paramedic said “It’s not like it was a tsunami or an earthquake or a volcano eruption. This is something we predicted and nothing was done about it.”

When confronted with the question of whether or not the B.C. NDP was prepared, Premier John Horgan responded by saying “fatalities are a part of life.” Horgan then insisted this was a matter of “personal responsibility” and that residents must “look after themselves and others.” It’s truly heinous that Horgan’s NDP can mobilize hundreds of volunteers to knock on doors during election season, but cannot do so when our most vulnerable are cooking to death alone in their homes. The NDP would go on to repeat this mistake in November 2021 when the Alert Ready system was not enacted as massive floods washed away highways, killing five and leaving thousands stranded.

In any case, even if a provincial heat alert was enacted, it still wouldn’t solve the problem that there is a complete lack of emergency services on a normal day. Calls to 911 doubled during the peak of the heat dome, and multiple people either had to wait more than 30 minutes for an ambulance, or they called and there was no ambulance to send. Dead bodies were literally piling up in hospitals. The staffing crisis for paramedics is so dire, recently the Ambulance Paramedics of British Columbia or CUPE Local 873 discovered that only a single ambulance was available in all of Vancouver at 6:30 a.m. on Feb. 2. Climate-change-driven emergencies aside, the opioid crisis as well as the continuing pandemic have stretched emergency services to the limit. It doesn’t matter how good the alert system is if there are no ambulances or hospital beds available for those who need them.

The second recommendation was to ensure vulnerable populations are identified and supported during extreme heat events. This will be completely necessary to stop future deaths, and it’s no wonder most who died were alone and poor without ventilation. But the question remains: who will identify and who will support them? Sixty-two per cent of those who died had 10 or more visits with a health professional within the 12 months prior to their death. They weren’t invisible to the system. Virtually all victims died indoors with neighbours nearby. Every neighbourhood should be given the resources, training, and information necessary to act quickly and decisively when needed. Everyone in a neighbourhood should know where the most vulnerable are and have the tools to help them whether in a heatwave, flood, cold snap, or earthquake. Non-profit community centers have taken to coordinating their own heat response plans and individual check-ins. There’s no reason why the government of one of the richest provinces in one of the richest countries in the world cannot do this

The final recommendation of the panel was the vague “Implementing prevention and longer-term risk mitigation strategies.” Ultimately many of the recommendations in the report don’t deal with the root cause of the heat deaths—namely, that much of the reason people died is hardwired into the infrastructure of our society.

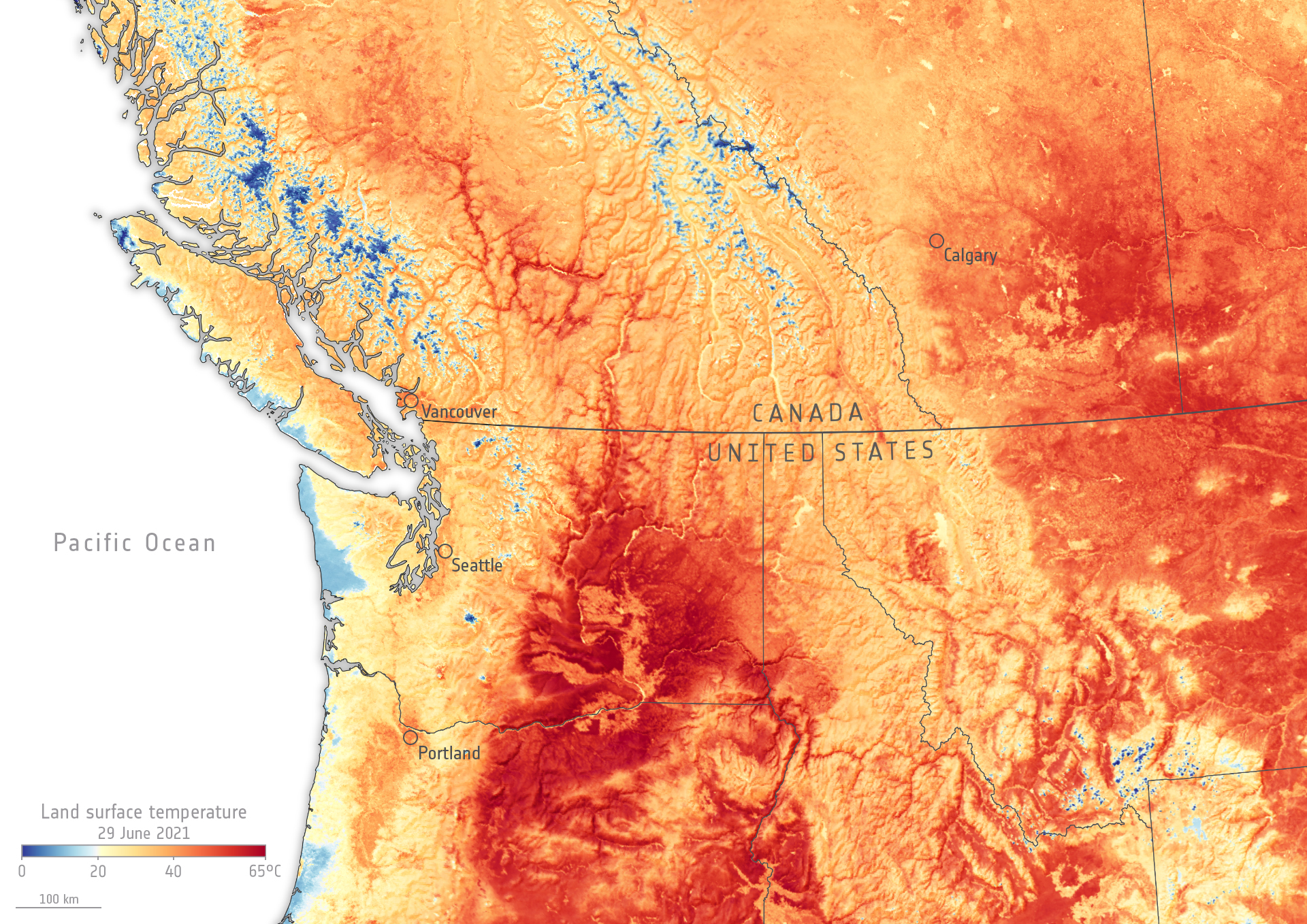

The panel cited a study which stated, “Poor quality housing, homelessness, and overall deprivation are risk factors for increased mortality during extreme heat events.” It’s not even a question of having AC. The amount of tree cover, the heat-island effect of cities, available parks, and quality of housing make cities much hotter than the surrounding countryside. As always, it is the poor and working class who suffered the most and died at disproportionate rates. Looking at a heat map of Vancouver, there is a clear dividing line between the hottest and the coolest neighbourhoods in the city. The poor, working class neighbourhood of Marpole was on average 20 C hotter than rich neighborhoods like West Vancouver, largely due to tree cover.

Even AC is not a long term solution. Not only do AC units require power, maintenance, and parts that poor populations won’t have, cooling is incredibly power-hungry. In 2005 the U.S. used more AC than all of Africa–home to 1.2 billion people in a much hotter climate—consumed for all its uses, and today about a fifth of all global electricity is used for cooling. Carbon emissions from AC in the U.S. are greater than those from the entire construction industry. The positive feedback loop on a warming planet should be evident. But AC is not the only solution.

Planting trees, creating parks, building new housing, and retrofitting old housing can dramatically cool our neighbourhoods. But this will take a massive effort—essentially the rapid replanning of cities. In a televised conference, Dr. Jatinder Baidwan, chief medical officer of the B.C. Coroners Service, said the problem of heat deaths is huge and vast and is about changing the way that we live. This cannot be emphasized enough. But what does the report suggest as a solution? Tweaking building codes and creating rebate programs! The habitability of our buildings in the increasingly hotter climate will be put in the hands of landlords, arguably the group who cares about our communities the least. If the need for these changes is urgent, they must not be left to the discretion of landlords. There should be mass construction of socialized housing with the most advanced and effective cooling methods involved, and all private units should be mandated to provide cooling for every unit. If landlords refuse, then their units should be expropriated and run as social housing.

The panel review details the reasons people died with great detail: poverty, isolation, lack of planning, and lack of action. What it doesn’t do is state the obvious: these risk factors are direct consequences of capitalism. Poverty and homelessness continue to increase in Canada as profits rise. Climate change is driven by polluting companies for profit. There is no way to adequately deal with the crisis without overhauling our health-care system, lifting workers out of poverty, and replanning our cities. The reason none of this has been done is because the B.C. NDP has completely accepted capitalism and refuses to act decisively in the face of a growing climate emergency. Small tweaks to building codes will not save us from climate change. Only bold socialist planning and an attack against the profit motive can mount a serious fight against the conditions which led to hundreds of lives being lost.