Celebrations of the centenary of the birth of René Lévesque took place in Quebec last summer. Probably the most influential and popular politician in Quebec’s history, Lévesque is celebrated across the political spectrum. From left to right, from the Liberals to the CAQ, from Québec solidaire to of course the Parti Québécois, Lévesque is praised. But for Marxists, this anniversary is an opportunity to revisit and make a critical appraisal of the ideas and career of the former premier.

During the recent electoral campaign, the leaders of the five main political parties were invited to the popular talk show Tout le monde en parle and asked who was the best prime minister in Quebec history; all but the Liberal Dominique Anglade answered René Lévesque.

Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, the leader of the left-wing party Quebec solidaire, said at the launch of the centenary activities, in a true panegyric:

“René Lévesque appealed to the light inside us, to our generosity, to our solidarity; he looked for the best in each and every one of us so that we would rise together in a whole greater than the sum of its parts, a societal project stronger than the individuals that make it up.”

At the other end of the political spectrum, François Legault also had fine words for Lévesque:

“René Lévesque was one of the most significant Quebecers in the history of Quebec. His words and actions continue to inspire current generations of Quebecers. His famous quote, ‘We may be something like a great people,’ was a turning point in the way Quebecers perceived themselves. René Lévesque was a creator of pride. […] With Jacques Parizeau, he set up what was called Québec Inc. His government gave back control of the economy to Quebecers and allowed the development of a whole generation of Quebec entrepreneurs and flagships.”

Thus, with Lévesque, there is something for everyone. How to explain such unanimity throughout the political class, regardless of their political allegiance? How can Lévesque be worshiped by the left as well as millionaires? Marxists must understand the real place occupied by Lévesque in history, beyond all the myths.

The petty bourgeoisie and the revolution

Contrary to his future colleague Jacques Parizeau, born in a rich family and who never hid his bourgeois origins, René Lévesque was born in a modest petty-bourgeois family from New Carlisle, Gaspésie. His father was a lawyer and Lévesque, after his classical studies, went into law school himself. But at the beginning of the 1940s, he abandoned his law studies to be a full-time journalist. After working as a war correspondent during World War II for the United States (he stated he preferred this to working for His Majesty the King!), Lévesque became a celebrity working for Radio-Canada in the 1950s.

Lévesque rose to fame in the period known as the Grande Noirceur (the “Great Darkness”), the epoch of the domination of Maurice Duplessis and his conservative Union Nationale government. Under Duplessis, the Church was the moral police controlling people’s lives, suspected communists were repressed and the imperialists plundered Quebec.

In this context, Lévesque angered the establishment because he covered the struggles of the oppressed, which in itself was seen as an act of defiance. His biographer, Pierre Godin, recounts:

“His bias for the poorest, which many colleagues reproached him for, was undeniable. For example, he had his own ideas about the Murdochville strike, which the police, in league with Noranda [the company], tried to break. In the land of Maurice Duplessis, labour disputes quickly descend into abhorrence. In Point de mire [Lévesque’s show], with its film clips, maps, interviews and incisive judgments, the journalist casted a brutal but true light on the strike. He showed men whose rights were trampled on in general indifference, crushed miners who no longer believed in anything. For him, objectivity never rhymed with neutrality, obsequiousness or servility, even less with self-censorship.”

The mayor of Montreal, Camilien Houde, even went so far as to state in 1956 that “All leftists are on the television”. Lévesque was even suspected by the RCMP of being a communist!

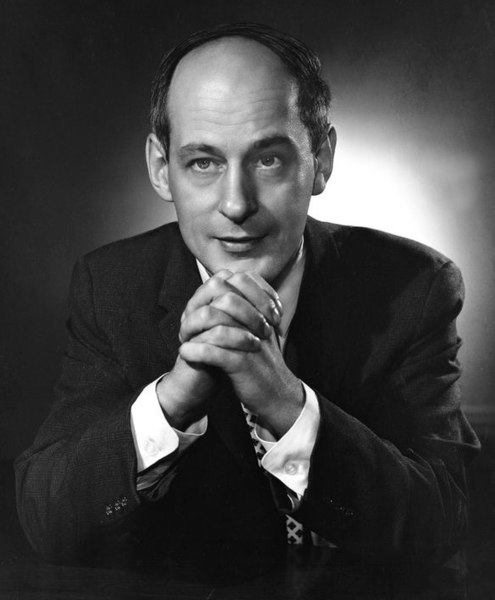

Source: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Lévesque’s path is typical of that of a whole layer of Quebec intellectuals of the time. Generally speaking, petty-bourgeois intellectuals are constantly under pressure from the two fundamental classes of society: the working class and the capitalist class. The petty bourgeoisie constantly oscillates between these two. Under the pressure of the struggles of the working class and the oppressed, petty-bourgeois layers can become inspired, enter the revolutionary struggle and become radicalized. Fidel Castro – to which Lévesque was later compared – is an extreme example of this phenomenon. Son of rich landowners, he became the head of a guerrilla group, considering himself a democrat in the style of Thomas Jefferson (he denied being a communist at the time). But Castro and his guerrilla force, under the pressure from the Cuban workers and peasants and in the face of the intransigence of the United States, went so far as to overthrow capitalism in Cuba.

In Quebec, the rise of the working class in the 1950s pushed many intellectuals to the left. Another famous journalist joined the opposition to Maurice Duplessis, and was even arrested on the picket lines of the 1949 Asbestos strike: none other than Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Lévesque’s future number one enemy. Gérard Pelletier, eventually editor-in-chief of La Presse, was one of the leading intellectuals of the 1950s and 1960s. They were good friends with Jean Marchand, president of the Confédération des travailleurs catholiques du Canada (the future CSN) and hung out with Michel Chartrand, the famous union leader.

Inspired by workers’ struggles such as Asbestos in 1949, Louiseville and Dupuis Frères in 1952, and Murdochville in 1957, intellectuals, lawyers, journalists, and professors entered into open opposition to the Maurice Duplessis regime; his conservative Union Nationale, the Catholic Church, and the American and Anglo-Canadian imperialism they served. The petty-bourgeois intellectuals were well aware of the economic and social backwardness of Quebec maintained by the Union Nationale, and wished to modernize the province and bring it into the 20th century. The working class and the petty bourgeoisie of Quebec were for a time marching together in the struggle against the Duplessis regime.

When we say that the petty-bourgeois layers were pushed forward and inspired by the workers’ struggles, it is not just a general remark. One specific example is the strike of the 74 Radio-Canada directors in 1958-59. Lévesque was one of the public figures of the strike.

What started out as a few days’ walkout to demand the unionization of directors became a conflict lasting almost 10 weeks. A non-unionized and typically petty-bourgeois profession (directors were considered managers at the time, which was why Radio-Canada tried to deny them union rights), the directors held out and led a heroic struggle thanks to the support of the employees of the corporation. Indeed, the 1,500 employees of Radio-Canada gave a huge boost to the strike when they refused to cross the picket lines, which paralyzed the corporation.

Lévesque was even arrested during a violent police assault on a demonstration in support of the strikers. The strike, which began on Dec. 28, did not end until Mar. 7, 1959, when the directors won unionization.

This strike was a landmark in the history of the Quebec nationalist movement. National tensions were exacerbated because management was overwhelmingly anglophone (just like the capitalists in the private sector). In addition, instead of calling for solidarity, the Anglo labour bureaucrats representing the bigger federations called their members to go back to work – essentially acting as strikebreakers. The indifference of the federal government also increased the anger. Lévesque hints in his autobiography at the impact it had on his ideological journey:

“Several hundred of us, seeing the conflict settle into the dreary routine of deaf dialogue, decided to go to Ottawa to plead our cause. Our delegation had the honour of being received by the Minister of Labour, Michael Starr, and were surprised to find that the paralysis of the entire French network was for him something that happened on the planet Mars.”

The following year, Lévesque left for new horizons: “I am done being a slave to Radio-Canada. In the future, I intend to move in new directions as I see fit…”. Of course, the petty bourgeois due to its class position in society, wants to do whatever they want without restraint. But capitalism offers us no such luxury. Cutting his ties with the labour movement inevitably thrust Levesque in the direction of the bourgeoisie.

Thus ends René Lévesque’s brief episode of militant trade unionism. He joined the Quebec Liberal Party at the dawn of the 1960 election.

From being a popular journalist and strike figure to being a celebrity candidate for the Liberals in the election, Lévesque began his rise to the establishment.

The petty bourgeoisie in power

The 40s and 50s were the period of the awakening of modern Quebec national consciousness. This coincided with the rise of the working class, which was predominantly French-speaking and exploited by predominantly English-speaking bosses. As Lévesque was joining the Liberals, the workers were discussing building their own party.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, the question of independent political action by workers was openly raised in Quebec, and in Canada as well. The unions came out in favour of a workers’ party, including the Quebec Federation of Labour (FTQ) in Quebec. The NDP was officially established in 1961 after a few years of preparation. Tragically, the Anglo-chauvinism and reformist reverence for the Canadian Confederation of the Anglo-Canadian union leaders entrenched nationalist sentiments among some of the Québécois activists and led to a split on national lines. The Quebec version of the NDP, the Parti socialiste du Québec, did not win the support of the unions and made no inroads, before folding in 1968 amidst general indifference.

In this vacuum, the petty bourgeoisie in Jean Lesage’s Liberal Party took the lead in the national liberation movement. The party soared to power on June 22, 1960, ending more than 15 years of rule by the Union Nationale.

After the death of Duplessis and the Liberal victory, a breath of fresh air blew over Quebec. The stifling Union Nationale regime gave way to a government that claimed to be on the side of the workers. The Liberals openly presented themselves as a break with the status quo under the slogan “Il faut que ça change” (“Things have to change”). René Lévesque was a member of the government as Minister of Water Resources.

The highlight of the Lesage regime was certainly the snap election of 1962. It was René Lévesque who succeeded in overcoming the opposition of his own party to propose the nationalization of hydroelectricity. To confirm popular support for the project, the Liberals called an election, which was for all intents and purposes a referendum on nationalization, under the famous slogan “Maîtres chez nous” (“Masters in our own house”). The party received the enthusiastic support of a large majority of Quebec workers.

During this period, René Lévesque was considered a serious threat by the Anglo-imperialist bourgeoisie. He was even dubbed the “Fidel Castro of Quebec” by the reactionary English-language press and the Union Nationale. He and Eric Kierans, another Liberal minister, were nicknamed the “socialist twins”.

Unsurprisingly, unlike Fidel Castro, whose nationalization measures led to the abolition of capitalism in Cuba, the Liberal Party’s measures had a different goal in mind. Demonstrating this, the aforementioned Kierans was known as the “socialist millionaire!”

Even the most audacious measures had to respect the framework of the capitalist system and not upset the elites too much. The nationalization of hydroelectricity under Lévesque was primarily intended to provide low-cost electricity in order to stimulate the development of private enterprise, especially in the regions. Similarly, the term “nationalization” is misleading: the Quebec government bought the shares of the 11 private hydroelectric companies at a total cost of $604 million. Three hundred million of this was financed by bonds sold on U.S. markets – an ironic way to become “Maîtres chez nous”!

Rather than an expropriation of the rich, this was a “state capitalist” type of measure, where the rest of the economy remained in private hands, and the company was run essentially like a private enterprise. Nationalization was presented in these terms by Lesage:

“Not only is the nationalization of electricity not the beginning of a general socialization campaign throughout Quebec, but I would even say that nationalization is an essential condition for the growth of private enterprise in the province.”

René Lévesque, for his part, explains in his memoirs: “[C]ontrol of such a vast sector of activity, essential to the development of each of our regions, would it not constitute a veritable school of competence, that nursery of builders and administrators which we so sorely needed?”

René Lévesque’s vision is on full display here. His objective has always been to create a distinctly Québécois capitalism with a seat at the table. And this is why he is celebrated by Quebec millionaires like Legault today.

The Liberals also established the Société générale de financement (SGF) in 1962. This state-owned corporation aimed to raise funds to finance Quebec businesses and reduce Quebec’s dependence on foreign capital. Then, in 1965, the Caisse de dépôt et placement was created to invest the colossal sums collected by the Quebec Pension Plan and other Quebec government accounts. By buying up Quebec government bonds on a massive scale, it helped reduce the domination of foreign banks. The nascent Quebec bourgeoisie was too weak to confront imperialism alone. The Quebec state was therefore to be used to stimulate its development and limit the role of foreign capital in the Quebec financial market. It is therefore clear that for the Quebec petty bourgeoisie, “Maîtres chez nous” did not mean that all Québécois would become the masters, but that they would simply replace the Anglo-imperialists.

The main measures of the Lesage-Lévesque government did indeed have the effect of laying the foundations for the formation of a Quebec bourgeoisie. Lesage explained it this way before he came to power:

“What I propose in the face of foreign capital… is an enlightened policy by virtue of which we would deal with the exploiters in all lucidity, businessmen to businessmen, ready to negotiate for the benefit of both parties.”

The reforms of 1960-1966 had been made possible by several factors. First, the Western world was experiencing an economic boom unprecedented in history. The boom allowed the bourgeoisie in many countries to make concessions to workers. Moreover, the post-war years saw a wave of labour struggles throughout the West that forced the ruling class to improve the lot of workers under threat of further radicalizing the working class. In Quebec the militant struggles of the 50s inspired the petty-bourgeois layers to stand up to Duplessis and the Anglo-imperialists and bring Quebec into the modern era.

There is no doubt that the nationalization of hydroelectricity, in particular, was popular with the working class. Indeed, while the measure was intended to help the development of capitalism in Quebec, it also reduced the cost of electricity for all Quebecers. In a time of national awakening, the symbolism of nationalization was strong, and helps to understand the nationalist myth created around René Lévesque.

Québec solidaire, the Liberal Party, the Parti québécois, the CAQ: all look to the government of Jean Lesage as an inspiration, and to Lévesque’s nationalization of hydroelectricity as evidence of great political audacity. In the context of Quebec dominated by imperialism, the nationalization of hydroelectricity was most definitely a bold measure. There is no doubt that in pushing for the nationalization of hydroelectricity, Lévesque personally played a key role in the formation of the “Quebec model,” and also ultimately in the formation of a distinctly Quebec bourgeoisie, the so-called “Québec Inc.” But the relative unity behind the Quiet Revolution could not last forever.

The PQ and the class struggle

The Quiet Revolution was only quiet in name. Far from being a period of simple reforms from above, the 1960s and early 1970s were rich in fierce class struggles.

Liberal reforms were incomplete and workers forced the party to meet their expectations. Workers had to force the Liberals to implement a labour code in 1964 which put into law the right to strike for almost all public sector employees.

The Quebec Liberal Party had always been a party of the establishment. Under the pressure of workers’ struggles, it came to power in 1960 on an ambitious program of reform and modernization. But the party quickly reverted to being a “reasonable” voice for the status quo. They had launched the slogan “Masters in our own house” and united the workers behind them. But this unity was disintegrating. The Liberals had for all intents and purposes created a modern Quebec capitalist state, but the workers wanted to go further. Towards the end of the Liberals’ mandate in 1966, the number of labour disputes skyrocketed, particularly among public sector workers, who were encouraged by their newly acquired right to strike.

The defeat of the Liberals in the 1966 election and the return of the Union Nationale to power was a political shock, and also coincided with an economic crisis, the return of inflation and unemployment. The Quiet Revolution was at an impasse. The crisis was reflected in all classes and in all parties.

The independence movement emerged from the margins during this period. The possibility of independence was even raised from the right by Daniel Johnson’s Union Nationale, which published its book Égalité ou indépendance in 1965. In the Liberal Party, it was René Lévesque who created the storm two years later.

In 1967, René Lévesque openly proposed “sovereignty-association”–-the idea of a renewed partnership between Quebec and Canada, where Quebec would become a sovereign country but with common institutions with Canada. In October 1967, he left the Liberal Party with a bang and founded the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (MSA). In October 1968, it became the Parti Québécois (PQ).

Lévesque’s PQ is often presented as the logical continuation of the Quiet Revolution. But this simplistic vision masks the class conflicts that marked this entire period.

In the workers’ movement, the late 1960s and early 1970s was a period of radicalization. The question of socialism and the creation of a workers’ party was openly discussed in the unions. This process of radicalization culminated in the revolutionary general strike of 1972. Liberal MP Jean Cournoyer explained this dynamic as follows: “It doesn’t shock me. This could have been predicted five years ago. That the nationalist movement was due to become class conscious.”

But the PQ went in the opposite direction. While the workers’ movement was generally moving to break from the ruling class, the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois politicians of the PQ were trying to find a way to reforge that unity by putting forward sovereignty.

The PQ, after all, was a merger of Lévesque’s MSA and the Ralliement national, a small right-wing nationalist party. Lévesque had never wanted to associate himself or merge with the independentists of the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale (RIN), which he considered too radical – let alone build links with the trade union movement. During the revolutionary general strike of the Common Front in 1972, René Lévesque said he would “rather live in a banana republic in South America than in a Quebec dominated by the ravings of the unions.” Once in power, he invited revolutionaries to leave his party.

While workers sought class solutions to the impasse of the Quiet Revolution, the PQ worked to create a broad coalition of all classes in Quebec in order to achieve sovereignty. As the labour movement became more and more revolutionary, Lévesque spoke of achieving “l’indépendance tranquille” (“quiet independence”). Lévesque presented sovereignty-association as follows: “To the simplicity of the main lines was added this other paradoxical advantage: far from being revolutionary, the idea was almost banal.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Quebec national liberation movement was propelled forward by the struggle of the workers against imperialism. The movement had an overwhelming class character; French-speaking workers were fighting against English-speaking imperialism. The openly anti-capitalist conclusions reached by the labour movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s were the logical conclusion of this process.

René Lévesque and the PQ, on the other hand, wanted to put Quebec sovereignty first, with the rest to be put off to an indeterminate future. The PQ was the ideal tool to channel the national emancipation movement and destroy the revolutionary traditions that had taken root. Unfortunately, most union leaders and most of the left supported the PQ and allowed it to co-opt the labour movement. Notable for this are the ex-FLQ leader Pierre Vallières, as well as the left-leaning RIN who dissolved to join the PQ. After the defeat of the 1972 general strike, most union leaderships pushed for supporting the PQ. We are still paying for these mistakes today.

Class peace

With the failure of the 1972 general strike and the absence of a workers party, the PQ rode the wave of discontent and took power for the first time on Nov. 15, 1976. The shock was immense. René Lévesque was seen as the enemy of the status quo with his plans for sovereignty-association, which meant ending Canada as we know it.

Source: L’agenda indépendantiste

The PQ had always tried to maintain the sympathy of the working class, with Lévesque speaking of his “favourable prejudice towards the workers.” But the party always maintained a distance between itself and the labour movement. In 1972, Lévesque moved the following resolution at the PQ convention: “With union members and their organizations, we share a fundamental goal of changing and humanizing the social and economic situation. […] But we must never lose sight […] that our time frames are not the same, our methods either, that their approach is essentially demanding while ours is essentially persuading […].” The PQ and Lévesque never wanted to be directly associated with the union movement. In reality, the PQ played the role of putting the lid on the enormous mass movement that had been shaking Quebec since the late 1960s.

Once in power, the first task of Lévesque was to quickly reassure the capitalists. His first budget, in April 1977, was an austerity budget. In his book René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois in Power, Graham Fraser explains: “His [Finance Minister Parizeau’s] real audience was on Wall Street, and he was cheered where he needed it most. Calling him ‘restrained’ and ‘disciplined’, investors were pleased…Five months later, Parizeau could appreciate the result: Quebec kept its AA credit rating on Wall Street.”

While presenting this “banker’s budget” aimed at satisfying the capitalists, the PQ made sure to keep its image of an all-class party. In May 1977, the party organized its first “economic summit” with representatives of the employers, the unions, and the government. This “dialogue” between the various “actors” in society is the trademark of petty bourgeois figures. The petty bourgeoisie is allergic to the notion of “class” and believe that it is enough to talk to each other to find the common interests of “society”. René Lévesque is the incarnation of this ideal. But Lévesque would demonstrate by his actions that once in power, a petty-bourgeois formation is forced to choose between the interests of the workers or those of the bosses.

At this summit, Lévesque sent a clear message that he was not attached to the labour movement. Faced with the protests of the leaders of the CSN and the CEQ in the face of the PQ budget, Lévesque called them “professional Cassandras who are killing themselves predicting that the apocalypse is for tomorrow morning if the entire economic system is not immediately abolished.”

Thus, Lévesque kept his distance from the workers. However, in preparation for the 1980 referendum, the PQ was forced to make concessions to win union support. The minimum wage was raised and the famous anti-scab law was passed.

Lévesque was not particularly happy with this pressure from the labour movement. He commented on the fact that the unions were asking for 30 per cent increases: “But it was not yet a crisis and appetites remained unlimited, as did the cynicism with which they had become accustomed to taking citizens hostage. Here and there, hospitals were closed, public transportation was paralyzed in Montreal. Once again, peace had to be bought at a high price, though not as ruinously as at the end of the previous rounds.”

“Buying peace” with the unions was necessary to get them to support the Yes side in the referendum. We have analyzed this referendum elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that it was not even about independence or national liberation. Lévesque was asking for the confidence of Quebecers to negotiate a new partnership between Quebec and Canada with bureaucrats in Ottawa. The PQ insisted during the campaign that nothing would change after the vote; that it was a mandate for “negotiation”, not “action”. Unfortunately, the union leaders latched onto the PQ’s carriage, and followed it in its project of “quiet” sovereignty, instead of fighting for their own interests through the methods of class struggle.

The ‘Butcher of New Carlisle‘

The fundamental characteristic of the petty bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeois politicians is hesitation, zigzags and contradictory policies. Since they are caught between the fundamental classes of society, the capitalist class and the workers, they tend to reflect the pressures of one or the other. They can at times implement policies to satisfy the workers, but under capitalism, once in power, they have to choose sides, and almost always end up bending to the pressure of the capitalists and implementing anti-worker policies.

After the defeat of the referendum, the PQ under Lévesque made a dramatic shift to the right. Former members of the Union Nationale took a growing place in the party. During the 1981 election campaign, Lévesque and the PQ appealed to conservatism to stay in power. It was a return to the themes of Duplessis: autonomy for Quebec, economic development, family. The PQ promised higher taxes for working women, and promised $10,000 grants for women who chose to stay home!

This conservative turn corresponded to a deep economic crisis. Two months after the 1981 victory, René Lévesque stated: “The time for all-out growth is over. […] Like all societies, without exception, Quebec is now faced with limits … from which it is absolutely impossible to escape.” The petty bourgeoisie in power was forced to accept the limits of the capitalist system.

The country entered a recession in 1981-82, and Quebec was particularly affected. Faced with a huge hole in the public finances, Lévesque imposed a 20 per cent pay cut for three months on all government employees, to apply from January to March 1983. He imposed new collective agreements on these workers and took away their right to strike.

The teachers defied the law and went on strike in February 1983. Lévesque retaliated with heavy artillery: Bill 111, nicknamed the “loi matraque” (“baton law”) imposed dismissal without right of recourse or appeal, loss of pay and seniority on any worker who continued to strike, and contained a clause suspending the application of the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This earned René Lévesque the nickname of “Butcher of New Carlisle”. To this day, these laws are among the most repressive in Quebec’s history.

For an honest appraisal of René Lévesque

The left and the labour movement suffer from a certain amnesia when it comes to appreciating René Lévesque. This period of his political career when his government viciously attacked workers is almost never mentioned. Yet, it is an essential link in the history of our movement, and of Lévesque’s career.

While the PQ and Lévesque were never political representatives of the working class and never pretended to be, they were definitely under the pressure of the working class majority to deliver the goods. What we can say about René Lévesque is that, similar to many petty-bourgeois politicians around the world, he seriously believed he could reconcile the different classes like an arbiter. But the capitalist system does not offer this possibility – or at least, when concessions to the working class are possible, they cannot last long. In his memoirs, René Lévesque describes the 1981-83 crisis as follows: “If I am not mistaken, our government was the first to take the bull by the horns. Not that we were more perceptive than others, we simply had no choice.”

Lévesque expresses here the narrowness of reformism. Without a perspective of overthrowing capitalism itself, in times of crisis, there is no choice but to attack workers. Even the most sincere reformists must bend to this necessity.

Lévesque’s political career entered an irreversible decline at this point. The party lost two-thirds of its members between February 1982 and February 1985. As if it were not enough to move far to the right, Lévesque went so far as to propose putting sovereignty on the back burner and attempting to renew federalism through negotiations with Brian Mulroney’s federal Conservative government. This turn of events, dubbed the “beau risque”, led to a crisis in the PQ and massive resignations from the party cabinet in the fall of 1984, including none other than Jacques Parizeau. In January 1985, at a special PQ convention where the “beau risque” was adopted, Lévesque said: “It is not for nothing that from the beginning, 17 years ago, we have been talking not only about associated states, but even, if you remember, about a kind of new Canadian Community.”

Lévesque thus came full circle. Having succeeded in drawing the labour movement into his sovereignty project, and putting the lid on the radical struggles of the 1970s, Lévesque now set aside sovereignty itself in favour of negotiating the status quo with the federal Conservatives. On June 20, 1985, a worn out Lévesque resigned, shortly before the PQ was crushed in the election later that year.

There is no doubt that even today, Lévesque enjoys great popularity among the general population. He was a charismatic figure who today represents the national awakening of the 1960s and 1970s in the eyes of thousands of Quebecers. But beyond the appeal of the character, we must look at his entire balance sheet.

René Lévesque’s political trajectory is a historical lesson in the limits of class collaboration. During the post-war boom, and under pressure from the working class, concessions are possible and sometimes necessary, in order to buy peace with the workers, in the interest of the capitalist system itself. But all things have their limits, and this period was an exception in the history of capitalism, not the rule. Throughout the West, the 1980s were a period of retreat. The welfare state built in the post-war period was attacked from all sides in every country. Quebec did not escape this. With no prospect of overturning capitalism, Lévesque and the PQ had to make workers foot the bill, and bring out the heavy artillery of back-to-work legislation to crush them.

Lévesque embodied the petty bourgeois in power. Once in power, a petty-bourgeois figure or party comes under the pressure to serve the capitalist class, and typically answer by bowing to the master. The process continued and the PQ ended up becoming an openly bourgeois party, which was confirmed in the eyes of all when billionaire Pierre Karl Péladeau, the Québécor magnate, became the party leader in 2015. However brief his tenure was, such a thing would be unheard of even in the most degenerate workers’ party.

With the failure of the two referendums, the nationalist movement has slowly degenerated into a retrograde identity-based nationalism that attacks immigrants and minorities. The left and the labour movement must, once again, look at the big picture. The rise of the PQ and their sovereignty project cut short the radicalization of the working class of the 1960s and 1970s. Rather than tail-ending this movement, the trade unions should have created a working-class party separate from the federalist Liberals and the nationalist PQ. We are still paying for that mistake today.

One hundred years after his birth, 35 years after his sudden passing on Nov. 1, 1987, René Lévesque is celebrated by the entire political class. Even today, a mythology surrounds the first PQ government on the left. A few years ago, Amir Khadir, then a member of the National Assembly and spokesperson for QS, said: “The 1976 PQ government was a relatively social-democratic government which, in essence, is not so far from what we propose today.” But this is a mistake.

The government of Lévesque tried to please the workers and the capitalists but when push came to shove sided with the bourgeoisie. The same situation would be faced by any left-wing government that comes to power today. The left should not be resurrecting this tired failed strategy but must patiently explain that it is impossible to reconcile the interests of irreconcilable classes. A future QS government would, sooner or later, have to face the same choices as the PQ: make the bosses pay, or attack the working class. The entire history of social democracy in power demonstrates this.

Myths die hard. The Quebec left must look at the whole René Lévesque, not just the moments when he pandered to the working class. If the left and the labour movement are to avoid repeating the PQ experience of 1976-1985, all the lessons of that period must be learned.

Today, the idea of reconciling the interests of the nation’s bosses and workers is further from reality than ever. If it wasn’t possible in the 1980s, it is even less possible now that the real estate bubble is huge, inflation is at an all-time high, and a recession is preparing to hit a world that is more indebted than ever. Capitalism is in crisis and someone has to foot the bill. The capitalists want the workers to pay for the crisis of their system, and the living of working class people continue to decline. There can be no talk of reconciling the interests of the bosses and the workers in this situation.

Connected to this is the question of independence. We often hear that because powers are centralized in Ottawa, Quebec is unable to implement progressive reforms. The implication is that independence, in itself, would be a step forward in achieving this. An example of this is contained in Lévesque’s opinion of the famous manifesto Ne comptons que sur nos propres moyens (“It’s up to us”) and the document Il n’y a plus d’avenir dans le système économique actuel (“There is no future in the current economic system”), both published by the CSN in 1971. These documents called for the building of a socialist society and explained, among other things, why Quebec capitalism would not be a solution. Here is what Lévesque had to say about this:

“In my opinion, […] there are two big gaps in these two documents. Nowhere in these documents is independence mentioned as a prerequisite. I am sorry, but we have seen in the Western provinces governments with socialist tendencies, unable to carry out the socio-economic reforms contained in their program, because they lacked the necessary instruments, since the powers were centralized in Ottawa. In my opinion, it is therefore necessary to come into the world before choosing what we will be later.”

This argument is still very much alive on the Quebec left. But we have to ask, what would be different in a capitalist independent Quebec? In reality, in Quebec, the biggest obstacle to workers’ struggles and to the implementation of measures that improve their lot and that of the oppressed is “Quebec Inc.”, the Conseil du Patronat, the Péladeaus and Desmarais of this world. They are the ones who have pushed for a wave of austerity from the 80s and 90s to today. Anyone who argues for independence as a “prerequisite” must explain why they prefer the Québécois capitalists to their English Canadian counterparts.

The strength of the CSN manifesto, which Lévesque specifically criticizes, was to explain that it is the capitalist system that lies at the root of the continuing oppression of Quebecers and the exploitation of Quebec workers, not federalism as such, as this passage shows:

“For [the French-Canadian bourgeoisie], the problem is not capitalism, it is the fact that the capitalists are American or English-Canadian. So these people say to themselves: let’s make sure that the decisions are made in Quebec […].

[…] In short, the great illusion that the advocates of the thesis of an independent capitalist Quebec want to maintain is that it is possible to civilize foreign capital by imposing limits on its action […]. But where is the interest of the workers in this game of competition: whether it is private capitalism or state capitalism, the fate of Quebec workers will remain tied to the capitalist regime that will perpetuate the exploitation of their labor power.”

The manifesto pointed to a revolutionary and socialist solution to the Quebec national question, rather than to unify with our capitalists and petty-bourgeois nationalists. The labour movement was fighting for its own interests and came to realize the need to fight against capitalism itself and for socialism, as well as for a true national liberation implicit in that struggle.

This is what we need today. The labour movement needs its own voice, its own party and to seek its own independent road. We should reject any class collaboration in the name of the “unity” behind sovereignty, which is the path that Lévesque had traced. The idea of putting independence forward front and centre and of uniting the “sovereigntist forces” has consistently led down the path of watering down any socialist or working class demands in favour of uniting with bourgeois and petty-bourgeois elements. It led to the defeat of the workers then, and it would lead to defeat today.

We have entered the deepest crisis in capitalism’s history. Big class battles are on the horizon. The labour movement and the left need to put socialism front and centre, and unite the working class behind such a program. This means, ultimately, that the left and the labour movement should reject the political tradition embodied in the person of René Lévesque. He himself kept at a distance from our tradition and movement, and there is no use in reviving or celebrating the class collaborationist approach he defended.

It is time for the labour movement and the left to have an honest appraisal of René Lévesque. Understanding fully our past history, our defeats and our victories, is essential in order to prepare the victories of the future.