After more than 20 years in power, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has extended his rule for another five years after a multi-party opposition, led by bourgeois liberals, failed to deal his crisis-ridden presidency a decisive blow in the second round of the presidential elections on Sunday.

After failing to clear the threshold for the first time ever in the first round, Erdoğan managed to secure victory in round two, with 52 percent of votes, after receiving the backing of Sinan Oğan of the ATA Alliance: a split from the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), and the third presidential candidate, who secured 5 percent in the first round.

Simultaneous parliamentary elections took place in the first round, in which Erdoğan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) secured a majority with the help of three coalition partners, collectively getting 313 seats in the 600-seat parliament.

The Turkish economy is engulfed in crisis. Skyrocketing inflation, a free-falling currency and double-digit unemployment have pushed 98 percent of the country below the poverty line.

The economic crisis has been compounded by the devastating 6 February earthquake, which left nearly 60,000 dead (according to official figures) and nearly 3 million people homeless. Anger against the regime reached new highs given criminal corruption; the indifference and lack of preparation by the regime; and a mismanaged rescue response, that all exacerbated the catastrophe.

And yet Erdoğan and the AKP have survived, how can this be?

Polarisation

The voter turnout was at record-breaking levels: well over 80 percent, and possibly as much as 95 percent in both rounds. This is a reflection of the deep polarisation in Turkish society. The electorate went into the elections with high tensions and anxiety. On the day, three people (one poll station supervisor and two voters) had heart attacks in anticipation of the results.

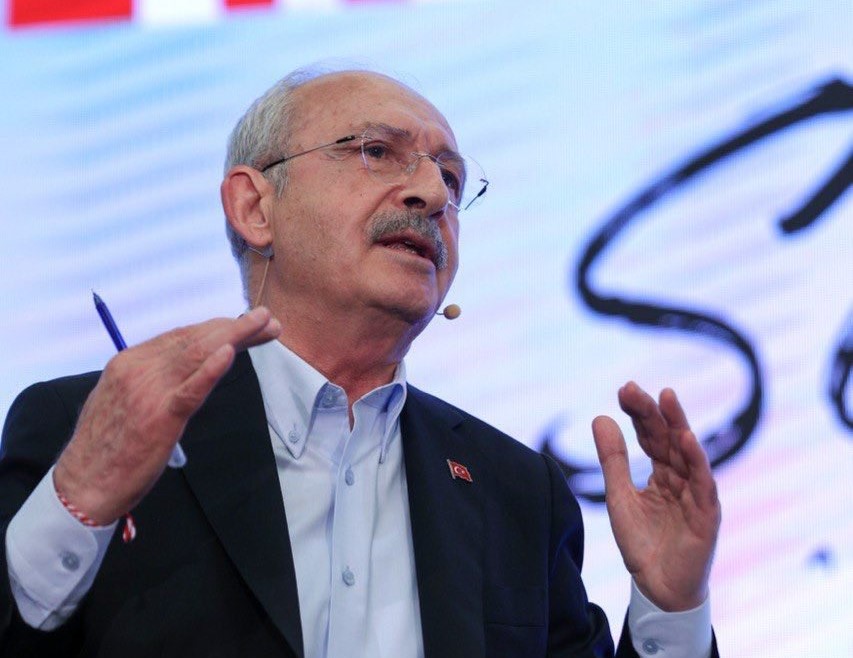

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the candidate of the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), led the Nation opposition alliance. Presenting themselves as the ‘responsible’ wing of the Turkish bourgeoisie, the opposition promised a return to “economic orthodoxy” and “restoration”: which means allowing the central bank to raise interest rates to tame inflation, and a reorientation towards the west, away from Russia and China.

But according to the Bank of America, interest rates would need to be raised to 50 percent to balance the current account deficit. This would have catastrophic consequences for the debt-saddled Turkish economy, leading to mass bankruptcies, unemployment and poverty.

And when Kılıçdaroğlu spoke about repairing Turkey’s relationship with NATO and the west, this only worked against him, as there is a healthy distrust of western imperialism in Turkey. Additionally, since the Turkish economy is heavily reliant on Russian gas, imports and tourists, a change in relations with Russia was never going to be a vote winner.

The CHP, once synonymous with secularism in Turkey, increasingly leaned on religion and chauvinism to appeal to the AKP’s base. Kılıçdaroğlu was only made presidential nominee after it was agreed the religious conservative Ekrem İmamoğlu (CHP mayor of Istanbul) and Mansur Yavaş (CHP mayor of Ankara, a far-right nationalist who split from the MHP), would be made vice presidential candidates.

Essentially, the opposition was promising a return to the early days of the AKP, but without the economic boom that gave them their authority. It is not hard to see why this failed to inspire confidence.

The CHP’s so-called liberal mask further slipped as it veered sharply to the right and aligned itself with far-right partners like the IYI Party. After failing to defeat Erdoğan in the first round, the party aligned itself with the Zafer party, a newly formed far-right anti-refugee party led by the rabid racist Ümit Özdağ.

Over the years, as the economic crisis has deepend, the opposition has stoked anti-refugee sentiments. In these elections, Kılıçdaroğlu demonised refugees, using racist language with statements like “women will not be able to walk the streets safely” if they aren’t deported. For the second round, the CHP ran an advertising campaign with the words: “The Syrians will go”, next to a picture of Kılıçdaroğlu.

None of this inspired support, and also repelled the most progressive elements in Turkish society. The fundamental dividing line in Turkey isn’t between natives and the refugees, but between the workers and the capitalists. As representatives of capitalism, Kılıçdaroğlu and the CHP cannot and will not present a class-based alternative, leaving them no option but to imitate the AKP’s chauvinist demagoguery.

It was also clear that the CHP was more concerned with containing the masses than ousting Erdoğan . After the first round, when the extent of Erdoğan’s electoral fraud was revealed on social media, rather than trying to mobilise protest from below, the CHP appealed for calm, issuing a pathetic statement that while there was cheating, “it will not change the results”.

Errors of the HDP

Unfortunately, the Kurdish-based, left-wing People’s Democratic Party (HDP) also committed a catalogue of errors. The HDP formed an alliance of far-left and left parties, the Labour and Freedom alliance. But instead of putting forward an independent class-based program, the alliance supported Kılıçdaroğlu in order to “get rid of the one-man regime”, and to “accelerate the democratic process”.

This was an appalling betrayal. The CHP, established in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who led Turkey’s bourgeois revolution, has historically persecuted the Kurdish people, banned the Kurdish language in public, and crushed Kurdish uprisings in 1925 and 1938, killing thousands of Kurds and forcing thousands more to flee.

In recent years, the CHP voted alongside the AKP for lifting the parliamentary immunity of Selahattin Demirtaş, the former HDP co-chair who has been imprisoned since 2016, and other HDP members of parliament. It has not raised any opposition to the removal of elected Kurdish mayors in the southeast. The CHP has also approved every operation of the Turkish army aimed against the Kurdish regions in northern Syria and Iraq.

In the run up to the elections, about 150 Kurdish politicians, journalists, lawyers and celebrities were detained by anti-terrorism squads, and Kılıçdaroğlu and the CHP did not utter a word.

Initially, the CHP-led alliance denied the HDP into its electoral alliance, in an attempt to court the nationalist vote. It only agreed to the HDP’s endorsement of Kılıçdaroğlu after it became clear it could not win without the HDP’s support and 6 million voter base. While the Nation Alliance did receive the HDP’s endorsement, they spent their whole campaign trying to distance themselves from the HDP.

As noted, days before the second round, Kılıçdaroğlu signed an agreement with the far-right, racist, anti-refugee Ümit Özdağ. While some HDP supporters held their nose and voted for Kılıçdaroğlu regardless, many did not vote at all. While the voter turnout across Turkey was nearly 94 percent, it sank to 80 percent in the Kurdish majority provinces.

The HDP suffered the biggest loss in the elections. In 2018, the HDP received 11.70 percent, and on 14 May they received 8.81 percent of the votes. Their MPs shrunk from 67 in 2018 to 62. The party lost votes in almost every city since the last elections in 2018.

If the HDP put forward a class-based programme and maintained an independent position, connecting the fight for daily demands of the masses to the fight for socialism, it would better cut across national lines and unite the Turkish and Kurdish working class. This would pose a much-greater threat to Erdoğan.

Erdoğan’s manoeuvres

For his part, Erdoğan campaigned skillfully. He was careful not to draw too much attention to the economy, and combined tall tales with bribes.

In the run up to the elections, he raised the minimum wage by 55 percent. Several days before the elections he gave a raise to civil servants, more than doubled the standard pension and passed a law making millions of workers eligible for early retirement. He also offered free natural gas for one month to households.

He centred his campaign around “a fight against terrorism and imperialism”, arguing he was the only one who could offer “stability”. He accused Kılıçdaroğlu and the CHP of working with “terrorists”, referencing their endorsement by the HDP. At one rally, he showed his supporters a faked video showing a PKK commander singing along with the leaders of the opposition.

He also accused Kılıçdaroğlu of being in talks with the IMF, and in alliance with the west and imperialists to turn Turkey into a “beggar”, an accusation that was assisted by Kılıçdaroğlu’s own statements. In order to blur class interests, Erdoğan also accused the entire opposition of being “LGBTers” and against “family values”.

With the majority of the media under his control, he spread his campaign far and wide, while limiting the opposition’s airtime. The regime also made hundreds of arrests of lawyers, journalists, activists and celebrities in the weeks leading up to the elections, most of them Kurds, to further repress the opposition’s campaign and create an environment of fear.

It is also clear that the AKP cheated. As soon as the elections got under way, videos and images of vote-rigging began to surface on social media, showing extra white voting bags filled with ballots: all for Erdoğan and the AKP.

In the earthquake region, which impacted 15 million people, the voter turnout was over 80 percent. In the southeast, in Kurdistan, the far-right nationalist MHP made significant gains. The YSK, Turkey’s electoral board was forced to overturn a seat for the HÜDA-PAR to the HDP in Urfa, after a recount was called.

It is true that the AKP still has a certain loyal base, particularly amongst the Anatolian middle-classes who benefited from the economic boom in the 2000s.

Nevertheless, Erdoğan and the AKP’s decline is evident across the country, in the major cities, and most importantly in his strongholds. Despite all the vote-rigging, media control and intimidation, Erdoğan was only able to secure the presidency with the backing of Oğan, in addition to fringe parties like the Free Cause Party (HÜDA-PAR), and the New Welfare Party (YRP).

In all, the AKP got 266 seats, which includes three seats for the HÜDA-PAR, who ran on the same ballot as the AKP. This is a fall from 296 seats in 2018 for the AKP alone. The MHP won 51 seats and the YRP won 5 seats.

In Kayseri, the ‘birthplace’ of Erdoğan’s AKP, the AKP’s vote share fell from 50.64 in 2018 to 40.62. In Konya, an ‘Anatolian Tiger’, the AKP saw a decline from 59.51 to 48.07. In Kahramanmaraş, a stronghold of the AKP (but also the epicentre of the 6 February twin earthquakes), support for the AKP declined from 58.54 in 2018 to 47.79.

In Gaziantep, another stronghold, which was also impacted by the earthquake and was the site of a strike wave last year, support for the AKP declined from 51.45 to 44.93. In Sivas, support for the AKP declined from 54.73 to 40.5. In Rize, Erdoğan’s hometown, his vote share fell from 64.99 to 54.07. And in İstanbul and Ankara, the AKP fell from 42.7 to 36.2, and 40.2 to 32.6 respectively.

But putting this, and all the foul play aside, the reason this decline hasn’t led to an outright defeat is because the masses still do not see a credible alternative to Erdoğan and the AKP.

Speaking with the Washington Post, one woman in Sivas said that she was concerned about “education, the economy, and for everyone to be able to express their thoughts and opinions”, but voted for Erdoğan. “Of course,” she said, “if there was a better candidate in the opposition, I would have voted for that candidate.”

A pensioner added: “unemployment is up to your knees here”, but that he had voted for Erdoğan and said “Let me put it like this. If a decent candidate had stood, he would not have won.”

Fragile foundations

But while Erdoğan can celebrate his narrow victory for now, he has inherited an economy in shambles. Rampant and uncontrollable inflation, which soared to 85 percent in October, and remains at 44 percent according to official figures, is creating a deep cost-of-living crisis for the masses.

Erdoğan’s options are unpalatable. He can raise interest rates as ‘orthodox’ bourgeois economics dictate and tackle inflation, but this would set off a chain of mass bankruptcies. Or he can slash rates to continue to keep the economy afloat through credit, but this fuels inflation and the cost of living crisis. For now, Erdoğan has chosen to proceed with the latter.

In the run up to the elections, Erdoğan intensified his defence of the lira, but the central bank is rapidly running out of foreign reserves and gold to keep the currency afloat. Reserves hit their lowest level since 2002 last week.

Together with Erdoğan’s pre-election spending spree, the 6 February earthquake’s estimated cost of $100 billion is only widening the deficit. This is expected to create a new burst of inflation, and the lira’s freefall has already resumed. Erdoğan is desperately in search of cash, turning to friends and foes alike for assistance.

Selva Demiralp, an economist at Koç University, spoke with The Economist during the race, saying: “They’re trying to sustain the current system until the elections, before it blows up”.

A political crisis is already being prepared, with the economic pressure causing anger to rise from below, opening up cracks within the ruling alliance as MPs feel the heat from their constituencies. This pressure within the parties is expressing itself in divisions within an already fragile alliance.

Erdoğan and Bahçeli may be able to ‘contain’ their parties for the time being but as the crisis deepens, it is only a matter of time before all the discontent erupts out into the open.

And much more importantly, the deepening crisis of Turkish capitalism will cause the class struggle to intensify. To cope with this, the ruling class needs strong leadership. Instead, it will have a feeble and fractured alliance of parties, welded together as part of a marriage of convenience.

No more popular fronts! For a working-class alternative!

The bankrupt strategy of ‘lesser-evilism’ has rendered the Turkish left exhausted and demoralised. In a heartbreaking news report, a 20-year old woman committed suicide in a train station in Marmary as the AKP’s victory became evident. The young woman left a note stating that “the AKP has stolen [her] youth”, she has “lost hope”, and she “will not forgive those who support the AKP.”

The entire left fell behind the so-called liberal CHP of Kılıçdaroğlu, which is the Kemalist wing of the ruling capitalist class, and fundamentally represents the same interests as the AKP, all of which are deeply discredited in the eyes of millions of Turks. In the end, they were dragged down with him to defeat.

It is true that the far-right and right-wing parties made gains in the elections, but this is only because there was no real working-class alternative. The masses are looking for a way out of this crisis, but no political point of reference is forthcoming. These results were not evidence of a rightward shift in Turkey, but only of the pathetic weakness of the liberal and reformist opposition. Any vaguely credible, class-based programme probably would have likely dislodged Erdoğan .

While the rest of the Turkish left is full of despair, the Marxists are optimistic about the future. Erdoğan’s crisis-ridden regime has never been weaker, and he cannot rule in the old way as the crisis deepens. Moreover, the Turkish working class is the largest in the region and it is beginning to take action. We highlight the strike wave that swept across the country last year, which was the biggest since the 1970s and the ongoing strikes and protests. This is only a foretaste of what is to come.

The conditions for an explosion of the class struggle are being prepared today in Turkey. The only thing that is missing is a revolutionary leadership to guide the masses along the path of struggle, towards a socialist future.