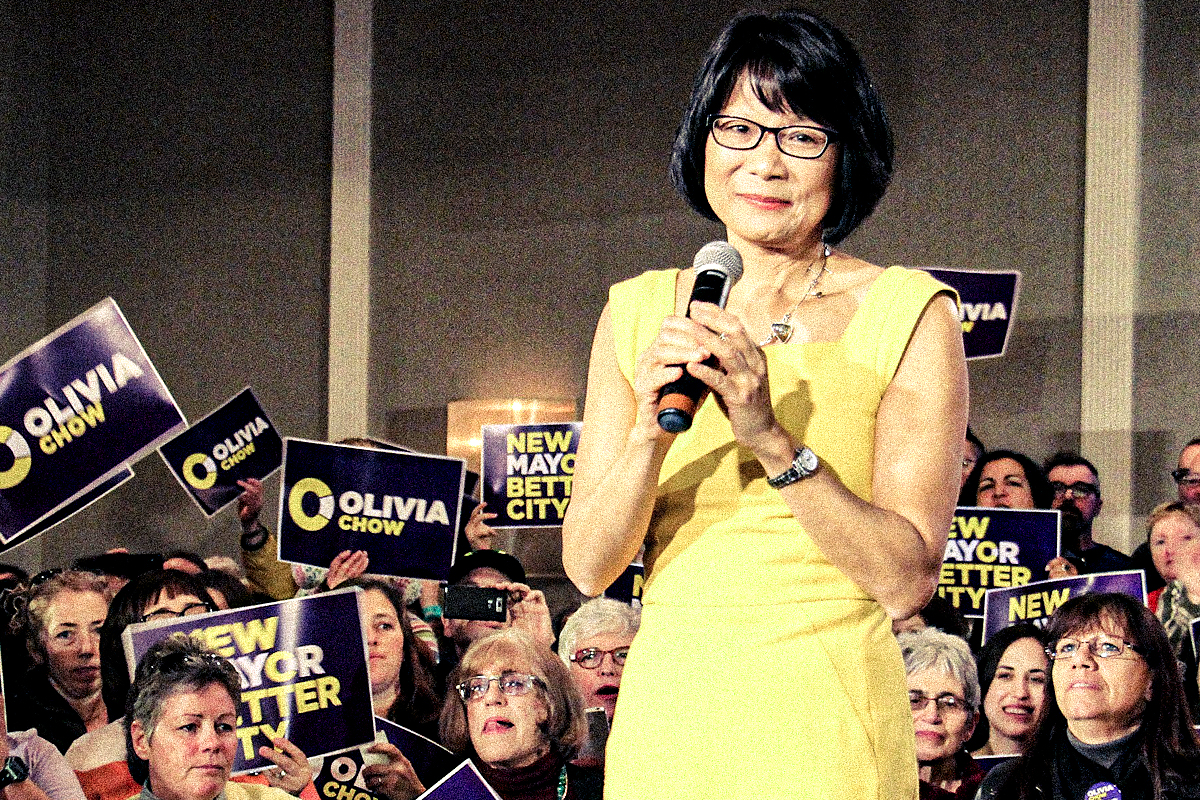

Olivia Chow, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On June 26, former New Democratic Party MP Olivia Chow was elected mayor of Toronto, promising to reverse past mayors’ cuts and lower the cost of housing. Looking at the details, however, it is highly doubtful that Chow’s moderate candidacy or her self-described “modest” platform will withstand pressure from the city’s bosses and landlords.

‘The city is in crisis’

Assessing Toronto ahead of the election, The New York Times wrote, “The city is in crisis after more than a decade of steep budget cuts for social services and the devastating withdrawals of fiscal support.” This helps explain why the resignation of Toronto’s right-wing ex-mayor, John Tory, saw a complete collapse in support for the candidates closest to his regime. Instead of an obvious Tory replacement, former New Democrat MP Olivia Chow was elected mayor—despite opposition from Premier Doug Ford, the police, and much of the media.

Tory’s deputy mayor, Ana Bailão, came second despite an endorsement from the Toronto Star, Tory himself and a long list of current and former MPs. After Bailão, no other major candidate—including city councillor Brad Bradford, former police chief Mark Saunders, and Postmedia columnist Anthony Furey—secured more than 10 per cent of the vote. Their campaigns to demonize the city’s homeless and capitalize on a string of recent violent incidents to bolster their plans for new police crackdowns on the poor combined into a result which, the National Post observed, “can generously be described as utterly lackluster.”

Chow’s incredibly ‘modest’ proposal

As the Post observed, Chow’s campaign mobilized a layer of “downwardly-mobile young professionals” in the city’s core. But the city’s poorest areas—including those hit hardest by council’s past cuts—saw virtually no change in their turnout. While the total vote was technically an increase from the 2022 election, that election also saw the lowest voter turnout in the city’s history at just 29 per cent.

Overall, Chow’s 269,372 votes out of a total 1.89 million eligible voters hardly represent a groundswell of enthusiasm. Part of this lack of enthusiasm reflects the reality that Chow does not offer a substantial challenge to the status quo.

While some have called Chow’s election a “win for the Left,” Chow distanced herself early on from any suggestion that she was leading a left-wing campaign, saying: “Whether we are left, right, or centre, let’s come together.” After spending much of her public life comfortably on the right of Canadian social democracy, Chow has already signaled a willingness to compromise with the city’s owners further—encapsulated in her slogan: “Collaboration, compassion and conviction.”

Assessing Chow’s platform

Chow’s plan—to “open city hall” to “business” and “labour”, and “make city hall care about us a bit more”—has few concrete proposals to end austerity and reduce the city’s steadily rising rents.

On transit, after decades of cuts, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) is on the edge of collapse, held together in some parts by duct tape and some of the highest transit fares in the world. Chow’s campaign, in the face of this, promised only to reverse “recent cuts” and restore the service’s funding—but only to pre-COVID levels. It is hard to see why anyone who used the TTC in 2019 would find this sufficient.

Acknowledging that Toronto’s rents are among the least affordable on earth, Chow’s campaign also said, “You should be able to afford a place to live in our city.” Looking at the details, however, Chow’s platform falls far short.

The campaign promised an increase in “rent supplements” for low-income tenants—more accurately described as subsidies to the landlords of low-income tenants—and construction subsidies to developers and other landlords. Specifically, Chow’s campaign promised to subsidize the construction of 25,000 housing units on city-owned land. Just 2,500 of these, if they’re built, will be geared to income. And only 7,500 will be “affordable”, in the city’s terms, defined as up to 60 per cent of market rate, in a context when the market rate is always rising. The other units, if built, will be set entirely at market rate.

This might increase the housing supply. But amid record low vacancy rates, the rents on these units will in large part be pegged to the extortionate rents set by the city’s landlords. This is hardly a surprise as, in 2014, Chow made virtually the same promise flanked by two corporate landlords from Medallion and Greenrock Investments Ltd, promising them “financial incentives and [a] fast approval process.”

The right wing, including Toronto’s former police chief, claimed Chow would also work to restrict the powers of the city’s police. But they can presumably rest easy given that, as the right-wing Toronto Sun admitted, Chow’s platform makes absolutely no mention of the police.

Chow also promised to campaign for “economic inclusion” across Toronto. There is no doubt that the city is becoming more unequal—alongside a record number of billionaires, Toronto’s homeless population has expanded to a record 11,000. But whatever changes Chow is proposing, she has made it clear that Bay Street will not be threatened.

“Toronto is the financial centre of Canada,” Chow said, “and to build a strong Canada you need a livable and affordable and healthy Toronto. And, right now Toronto has some problems.”

The city’s revenue crisis

The day after the election, the Toronto Star further observed that Chow, upon taking office, “will immediately be confronted by a slew of crises that threaten the future of Canada’s largest city.”

Chow’s platform, most immediately, will have to contend with the city’s $1.5-billion budget shortfall. According to The Globe and Mail, the city’s budget shortfall will rise to a staggering $50 billion over the next decade, larger than the city’s entire $46-billion, 10-year capital budget.

“The budget deficit that is in front of city council is very serious,” Chow said.

As the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives noted, a chief cause of the city’s ballooning deficit is the downloading of services from the provincial and federal level: “senior governments have downloaded major responsibilities, like social housing, to municipalities without providing the tools to pay for them.”

But asked about plans to raise revenue, Chow was non-committal, telling reporters, “I can’t give a number.” While the city funds a long list of social services, it cannot issue bonds. Its taxation powers are also limited to either user fees, like transit fares, or property and land transfer taxes.

As we’ve explained before, the property tax is a flat tax. While it raises revenue from the wealthiest, for workers and petit bourgeois layers who own a home, it also means a pay cut.

The land transfer tax targets a portion of the sale price of property within the city, for residential or commercial purposes. On top of having many of the same problems as the property tax, business groups have threatened to leave if the land transfer tax rises substantially. Asked about the plan, the president of the Toronto Region Board of Trade said, “We do know of executives and headquarters of businesses that ultimately relocated out of Canada to lower-cost jurisdictions because at a certain point, it just wasn’t worth it.”

To this end, Chow has admitted that her planned tax increase will indeed be “modest”, and unlikely to address the shortfall. Instead, speaking later about the deficit, Chow clarified instead that her plan is to “learn from the department heads.” (our emphasis) This is a softer way of saying that Chow will work with the city’s Tory-appointed public sector bosses to find cuts.

We’ve seen this before. In the early 1990s, then Ontario NDP Premier Bob Rae worked with the province’s public sector “department heads” to manage the province’s deficit—by attacking their workers. And in the early 2000s, then Toronto mayor David Miller similarly managed the city’s revenue crisis by setting up an “Economic Competitiveness Advisory Committee.” That committee helped plan a general austerity program for the city’s workforce and the poor. When carried out, it destroyed any lingering illusions workers may have in the “progressive” inclinations of moderate reformists in a time of crisis. It also paved the way for the right wing to return to power at both levels of government.

Prepare for struggle

Prior to Chow’s election, Toronto was facing a major revenue crisis, a housing crisis, rising poverty, and collapsing services. Aside from failing to resolve the city’s financial woes, whatever tweaks Chow applies to the tax code, her platform leaves power comfortably in the hands of the city’s bosses and landlords. While it is unclear how and if the platform will actually be implemented, it is clear that the crises facing the city will intensify.

Meanwhile, polls and elections, while an imperfect metric of general opinion, show signs of discontent across society. Most are not fooled by the right wing’s push for police budget hikes with one hand and service cuts with the other. This reflects the polarization of society. And it will continue during and after Chow’s tenure.

The fight to ensure housing for all, to end poverty and homelessness, and to defend working class lives and livelihoods is a fight against the city’s bosses and landlords. The task of socialists, in this context, is to prepare for struggle.