As the world becomes a more dangerous place, it seems we are once again being asked by our governments to love the bomb.

Trump’s policy of increasing isolationism, with threats to withdraw US support for Ukraine and NATO, has created a state of panic among the European powers.

They are running around like headless chickens. If America pulls back, they fret, who is going to defend Europe? Can French and British nuclear weapons provide protection to the rest of the continent? If not, should other countries seek to develop such capacities?

In the rush to rearm, Donald Tusk, the Polish prime minister, has raised the idea of Poland acquiring a nuclear arsenal. German officials have been wondering aloud whether they should follow suit.

Of course, much of this growing chorus – of the need for the bomb, again the bomb, and once more the bomb – is bluff and bluster. The Europeans, especially Macron, are like the mouse that roared.

Nevertheless, there is a serious side to such rhetoric. Fearful of a resurgent Russia, with Putin winning the war in Ukraine, European leaders all agree that defence spending must rise – and rapidly!

According to Sir Keir Starmer: “Russia is a menace in our waters, in our airspace, and on our streets.”

And accompanying this mania for greater militarism and more state expenditure on ‘defence’ is the need to prepare public opinion for the massive sacrifices that lie ahead, in terms of savage cuts to welfare and services.

Global disorder

A new situation has opened up internationally. Instead of globalisation, economic nationalism now rules.

This is graphically illustrated by Trump’s ‘America First’ policy, which means everyone else is last.

In a world of increasing tensions, every country is out to defend its own interests. With this comes the rise of protectionism and the threat of a global trade war.

The European leaders have been scrambling to rescue something from this crumbling postwar order. But Trump has told them in no uncertain terms that they can no longer rely on US security guarantees.

“We finally need to wake up and realise: ‘This is it’,” said one senior EU diplomat. “We are on our own. The parents on the other side of the Atlantic have just turfed us out of the family home, cut off our allowance, and disinherited us.”

After decades of fawning before US imperialism, the Europeans have now been caught with their pants down.

Their unconditional support for the war in Ukraine has suddenly become an albatross around their necks. Having hitched themselves to Zelensky, they are now facing defeat and complete humiliation. Such an outcome could not have come at a worse time.

They are looking to boost military spending precisely at a point when the crisis of European capitalism is intensifying.

Growth is extremely sluggish. Germany, at the heart of the EU, is in recession. A mountain of debt is weighing down on the European economy. And this is growing, becoming increasingly unsustainable.

As a result, whilst pouring billions extra into ‘defence’, there is also a need for deep cuts in social spending. But there is already a mood of burning anger against austerity in society.

Decline and decay

Any talk of a ‘peace dividend’ has long gone. Instead, all the talk now is about rearmament and increased militarism.

Starmer has taken the lead in banging the war drum. The ‘Labour’ leader has been at the forefront of this frenzy. “Britain will play its role on the world stage”, he says. “We are prepared to put boots on the ground in Ukraine.”

This is all about prestige, without any substance. Everyone knows that Britain’s power has been in decline for the last 100 years. The loss of empire and decades of economic decay have reduced Britain to a third-rate power on the world stage.

The UK’s ‘independent’ nuclear deterrent, in reality, is totally dependent on the United States. The reliability of this expensive system, meanwhile, was brought into question when the last two test Trident missiles veered off course and failed.

Embarrassingly, Britain’s two aircraft carriers are rarely put out to sea with a full complement of planes. The UK army is numerically weaker than at any point in the past 200 years. The country’s generals can scarcely raise one properly supported division, let alone wage a serious war.

No wonder Starmer’s supposed ‘coalition of the willing’ has become a laughing stock, dismissed by Witkoff, the US special envoy, as “posture and a pose”. He joked that, while the UK Prime Minister saw himself as a Churchillian leader, in truth he was tilting at windmills.

Debt and panic

Under Trump, the US is no longer seen as a trusted ally by the Europeans. They are therefore scrambling to rearm and become ‘independent’ from Uncle Sam. But this takes time and resources, which are in short supply. This explains the panic.

The big problem is that they have become completely dependent on US technology and weaponry. Almost two-thirds of the arms imported by European NATO members over the past five years were produced in the US. There is no quick fix for this reliance.

Amidst these fears, European security summits pledge ‘unity’ and more money for weapons. EU leaders have proposed to inject €150 billion into the European defence industry as a loan. But this has provoked a backlash from the cash-strapped Italians and Spanish.

Germany has removed its ‘debt brake’ to allow for greater military spending. But the weaker European powers are worried about being left behind in this arms race.

This potential borrowing has been described as a form of ‘military Keynesianism’ that, given Germany’s relatively low debt levels, could provide a short-term economic stimulus.

“It is very clear: the Germans can’t sell their cars, so they will make tanks,” said one French businessman.

At a European level, however, the prospect of large-scale borrowing has pushed up the cost of servicing the continent’s debts.

Warfare vs welfare

It is clear that defence spending, rather than providing a boost, will become a deadweight and a drain on the already debt-ridden economies of Europe, including Britain.

The UK currently spends 2.32 percent of GDP on defence – the equivalent of £64.6bn a year.

Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, has just pledged an extra £2.2bn, plus another £400m for the arms industry. And Starmer has announced that UK military spending will rise to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2027, to be funded through cuts to the foreign aid and welfare budgets. His ambition is then to reach a target of 3 percent in the next parliament.

With government debt running at over 100 percent of GDP, Starmer has ruled out further public borrowing. Instead, Labour will rely upon tax rises and cuts to funnel more towards ‘defence’.

The ruling class and its mouthpieces are encouraging Starmer and co. in this imperialist endeavor.

According to Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh, for example, “Europe must trim its welfare state to build a warfare state”. He says that high levels of social spending were “the product of strange historical circumstances, which prevailed in the second half of the 20th century and no longer do”.

This reveals the future for the working class under capitalism: further brutal austerity and attacks.

Starmer and Reeves have made a start by cutting winter fuel payments to the elderly and slashing disability benefits, affecting the most vulnerable of society. This will result in an estimated 250,000 more people being pushed into poverty.

This is already producing a public backlash. Labour’s war on the poor is a recipe for big class battles.

Military Keynesianism

Like a thief caught in the act, Starmer has attempted to disguise this rearmament as part of a fanciful plan to “rebuild industry across the country”, with public investment to “provide good, secure jobs and skills for the next generation”.

Similarly, an article in the Financial Times discussed how defence spending should be at the centre of Britain’s industrial strategy, with a rapid transition from “green to battleship grey”.

Attempts to justify increased defence spending with references to ‘increased growth’ are a complete fallacy, however.

Advocates of this ‘military Keynesianism’ suggest that state stimulus was what brought about the end of the Great Depression. Didn’t inter-war rearmament spur growth?

The simple answer is no. The Depression came to an end with the mobilisation towards WW2, and with the world war itself. The European powers and their economies were then devastated by this conflict.

In economic terms, the war had the same effect as a slump, where the destruction of capital and commodities paves the way for a recovery.

US imperialism, which did not suffer any economic damage from the war, also helped to finance the postwar recovery with Marshall Aid.

But the main driving force for the global upswing was the decision at Bretton Woods to do away with the tariff barriers that had provoked a collapse of world trade in the 1930s. This allowed for increased economic expansion and investment.

‘Permanent arms economy’

In this period, there were some on the left who bent under the pressures of Keynesianism, seeing state expenditure as a solution to capitalism’s crises.

Tony Cliff of the Socialist Workers Party, for example, put forward the theory of the ‘permanent arms economy’ to explain the postwar boom. He also used this theory to ‘explain’ why there was no boom-and-slump cycle in the Soviet Union, which he defined as ‘state capitalist’.

The reason there was no boom-slump cycle in the USSR, however, was not because it was ‘state capitalist’, but because of the existence of a nationalised planned economy that was not subject to the laws of the market.

“The basic cause of capitalist crises of overproduction is the relatively low purchasing power of the masses compared with the production capacity of industry,” explained Cliff.

Consequently, he believed that ‘permanent’ arms expenditure by the state could provide the demand to absorb this overproduction, resulting in economic stability and growth.

But this is simply Keynesianism – namely a programme of state deficit financing. It is the same argument used by the left reformists today.

Writing during the Great Depression, Keynes famously suggested that the state should pay unemployed workers to dig holes and fill them in again.

The extra spending power from their wages, he said, would create additional demand, and therefore stimulate production and investment, leading to economic growth.

Military spending can be regarded in the same way. But instead of workers digging holes, it involves the capitalists digging graves.

What the Keynesians fail to understand, however, is that capitalism is not simply about creating demand, but profitable production, investment, and markets.

Today, overproduction expresses itself as ‘excess capacity’ or over-capacity. Even at the height of its booms, capitalism can only profitability utilise around 80 percent of available productive capacity. In a slump, this falls to around 60 percent.

This shows that capitalism, as a system, has reached its limits.

Boom and slump

“Overproduction of capital,” explained Marx, “never signifies anything else but overproduction of means of production…

“Capital consists of commodities, and therefore the overproduction of capital implies an overproduction of commodities.”

Marx outlined how the capitalists are able to temporarily overcome this crisis of overproduction by taking the surplus value created by the labour of the working class, and reinvesting it back into production. If this wasn’t the case, there would be a permanent crisis of overproduction from day one!

Of course, over time, this simply creates greater and greater productive capacity, resulting in a greater contradiction of overproduction.

It is through its slumps that capitalism destroys this ‘excess capacity’ and devalues existing means of production, thereby restoring profitability and preparing the way for a new upturn.

In the 1950-60s, capitalism experienced not simply a typical boom, but a prolonged upswing. Within this period, there were slumps, but these were hardly noticeable given the general upward trajectory.

Importantly, this robust dynamic of growth took place at a time when defence spending was actually falling – contradicting Cliff’s theory of a ‘permanent arms economy’.

In fact, the economies that performed best during the postwar boom were those that didn’t spend so much on their militaries, such as Germany and Japan, but who instead were able to invest this money into productive industry. This made these economies far more competitive.

German weapons manufacturers, meanwhile, also gained from global arms sales, providing an additional source of income for German capitalism, rather than an economic drain.

War economy

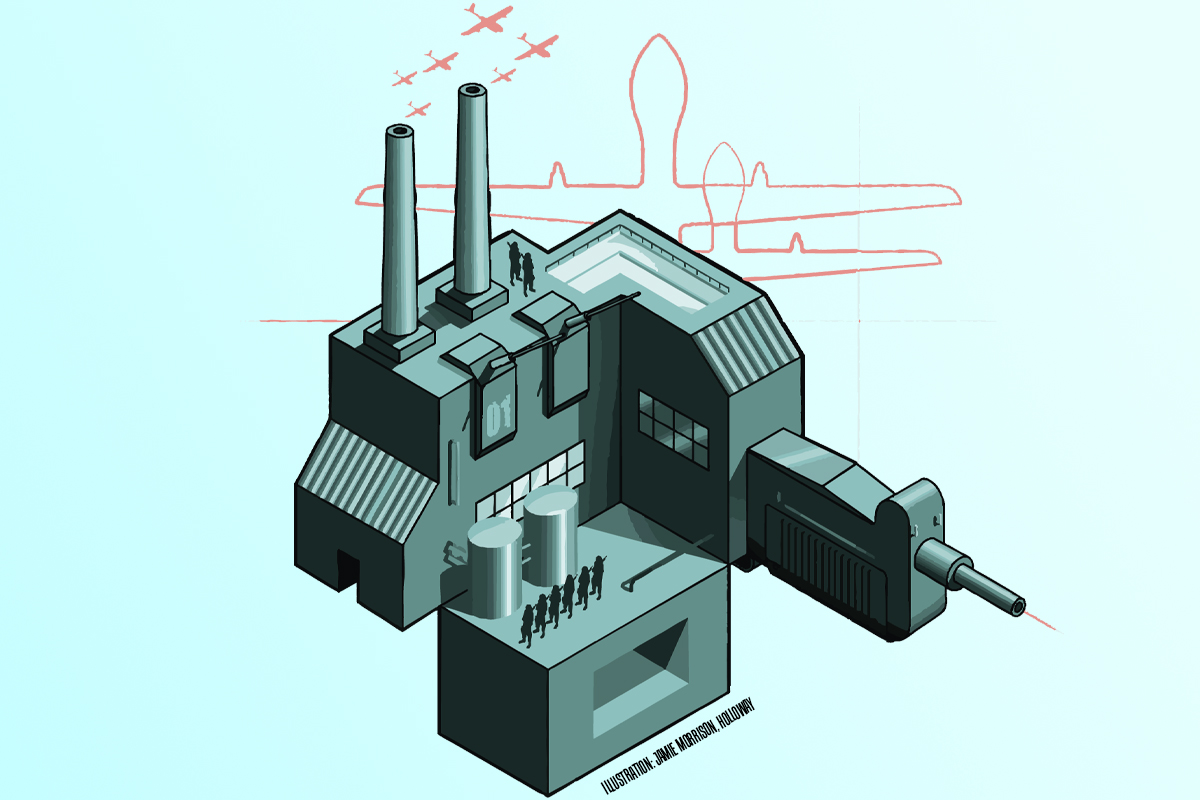

What happens when an entire economy is oriented towards war?

German capitalism became a war economy under Hitler. By 1939, military production accounted for around 68 percent of German economic output. But this was completely unsound economically.

Throughout this period, German capitalism was on the verge of collapse. Hitler and his regime were faced with the choice of waging war or facing oblivion.

In the end, Hitler waged war and conquered most of Europe, systematically plundering the continent’s resources and thereby (temporarily) staving off the German economic crisis. Mass-produced armaments were put to effective use, providing the means to increase the wealth of German imperialism.

In this respect, from an economic point of view, the arms economy produced a profitable return on investment for the German capitalists – until Hitler was defeated!

In reality, arms expenditure is a massive drain on the economy.

Following WW2, the United States became the self-appointed policeman of the world. Serving this role, US imperialism waded into Korea, Vietnam, the Middle East, and other areas. But these wars proved to be a colossal burden for the US economy, turning American trade and fiscal surpluses into deficits.

Furthermore, the inflationary impacts of US military spending undermined the dollar. This led to the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971, which sent shockwaves across the world economy.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the USA were involved in an arms race. But these armaments were basically scrap metal. Rather than acting as a boost to their economies, military expenditure proved to be a dead weight.

This played an important part in undermining the Soviet economy – although the main reason was the bureaucratic mismanagement that strangled the planned economy.

Circulation, accumulation, and reproduction

Marx explained that all commodities have a use-value and an exchange-value. The use-value of a cigarette, despite its harmful effects, is to be smoked. The use-value of weapons is to be fired and used in warfare.

But most armaments, including nuclear weapons, are simply stockpiled. In reality, in this static form, they have the same value as a junkyard of discarded cars.

True, as a result of the Ukraine war, these stockpiles have been steadily diminished. And, of course, for the arms manufacturers, government contracts are a source of juicy profits. But this does not alter the overall nature of weapons in wider economic terms.

As with all capitalist corporations, the arms companies expect the average rate of profit – if not more – from the state.

To purchase these weapons, meanwhile, the state relies on taxes, which in turn come out of either the workers’ wages or the capitalists’ profits; that is, from the wealth created in real production.

Military spending, therefore, ultimately comes from the value produced by the rest of the productive economy.

In other words, money on arms represents unproductive expenditure from an economic point of view: spending that could otherwise be invested by the capitalists in means of production and labour-power to generate a profit; the siphoning of society’s economic resources out of the circulation and accumulation of capital.

Under capitalism, the working class is exploited by the capitalists to produce surplus value. This surplus is then appropriated by the capitalists and reinvested in industry. This is the process of capitalist accumulation, or ‘reproduction’.

Analysing this process, Marx divided the capitalist economy into two areas: ‘Department 1’, the production of the means of production; and ‘department 2’, the production of the means of consumption.

Both of these sectors of the economy are essential for capitalism to reproduce itself and expand.

A part of the surplus value created in production, however, is not reinvested, but is spent or consumed as revenue by the capitalists. This includes things like luxury goods. This slice of value is not part of capitalism’s cycle of reproduction.

Military spending operates in the same way as luxury goods. It is economically unproductive: money spent as revenue, not reinvested in production, and thereby not forming part of the circulation and reproduction of capitalism.

Leading Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin explained the situation as follows:

“War production has a completely different meaning [to capitalist reproduction]: a cannon does not transform itself into an element of the new cycle of production; gunpowder is shot into the air and in no way appears in a new shell in the following cycle.” (Bukharin, Economics of the Transformation Period, p44)

It is the same for living labour that is wasted in war. Soldiers play no role in the production process. Unlike workers, they are not used productively to create surplus value.

“The army, which provides a powerful demand, i.e. the need to be supported, offers no work equivalent,” explained Bukharin. “As a result, it does not produce but rather deprives.” (ibid, p45)

In other words, the army does not produce, but only consumes.

For the capitalist system as a whole, therefore, military expenditure is unproductive. It is a drain on the economy.

For the same reason, ‘defence’ spending contributes towards inflationary pressures in the economy.

This expenditure represents a form of fictitious capital, as Marx described it: money that circulates in the economy (e.g. in the form of the arms manufacturers’ profits) without any equivalent value in terms of real commodities.

State armies and weapons producers are ultimately competing to utilise the same economic resources as other – productive – sectors of the economy. This adds to economic demand, but without any increase on the supply side.

Hence the inflationary tendency of military spending, along with all other forms of unproductive state expenditure, like Keynes’ hypothetical hole diggers.

‘Guns before butter’

Until recently, capitalist governments were attempting to cut defence spending. They welcomed the so-called ‘peace dividend’ at the end of the Cold War, which meant that less could be spent on defence, and more on other things. But this era has come to an end.

Despite the idle boasts of Starmer and Reeves about making Britain “a defence industrial superpower”, the UK defence industry is too small to have any impact on the national economy.

According to the Ministry of Defence, arms spending directly supports around 130,000 full-time jobs. If supply chains are included, this figure rises to 209,000 – or just 0.83 percent of the workforce.

To believe that Britain can be transformed into a military-industrial superpower from this low base is pure fantasy.

Today, the UK has the sixth largest military budget in the world, which it uses to uphold the legacy of Britain’s imperial past.

Starmer wants to boost this by attacking the most vulnerable sections of society. He favours a policy of ‘guns before butter’.

Those who will benefit will be the likes of BAE Systems, the country’s leading weapons dealer, who have paid out £9.8bn to shareholders since 2015.

These contractors – along with the rest of the military-industrial complex – are large multinational corporations; bloodsuckers that live off taxpayers’ money.

In Europe, meanwhile, politicians are looking to pay for rearmament through greater state borrowing. Given the existing high levels of public debt, however, this will mean unsustainable interest costs – putting pressure on governments to cut expenditure elsewhere.

The ruling classes everywhere are determined to place the burden of militarism and capitalist crisis onto the backs of the working class.

Books not bombs!

For the working class, there is no way out on the basis of capitalism, which only offers austerity, war, and insecurity.

We resolutely oppose the rise of militarism. As communists, we aim to expose the cynical interests and hypocrisy of the capitalists and their hangers-on, whose aim is to deceive us.

Unfortunately, the trade union leaders have fallen for the capitalist’s lies. They support increased defence spending to help create more jobs for British workers.

But why must workers produce weapons to kill other workers in order to create jobs? Why can’t we produce socially-useful goods and services instead, just like the workers at Lucas Aerospace proposed in the 1970s?

It is true that the Barrow-in-Furness shipyard, for example, currently depends upon government contracts to build nuclear submarines. But in the early 1960s, its most profitable work was making engines for British Rail – a very productive contribution to society.

Capitalism has turned everything on its head.

As Khem Rogaly, a senior researcher at the Common Wealth think-tank, explains: “Policy choices have left communities dependent on military contracts because of divestment from public services and civilian industry.”

This development is a reflection of the anarchy of capitalism, which prioritises bombing schools and hospitals abroad rather than building them back home.

The capitalists and imperialists are guided by greed and the drive for greater profits, and nothing else.

We must oppose this capitalist madness. We oppose the drive for weapons of mass destruction, promoted by Starmer’s Labour, and by capitalist governments across the world.

Instead of a programme of rearmament, we call for a programme of socially-useful public works. We demand healthcare, not warfare! Books not bombs!

We stand for a socialist plan of production, where the resources of society are used rationally for the benefit of all.

Only by expropriating the billionaires and their lackeys can we achieve this goal, and create a world free from conflict, chaos and crisis.

This means fighting for nothing less than the worldwide socialist revolution.