Electoral reform is an issue that is periodically raised in Canada and Quebec. The distorted results of the recent Quebec election have triggered a wave of calls to get rid of the first-past-the-post system used across Canada and adopt a more proportional system. How do Marxists approach the question of electoral reform?

CAQwave

The results of the recent Quebec election have highlighted the weaknesses of the first-past-the-post system used across Canada.

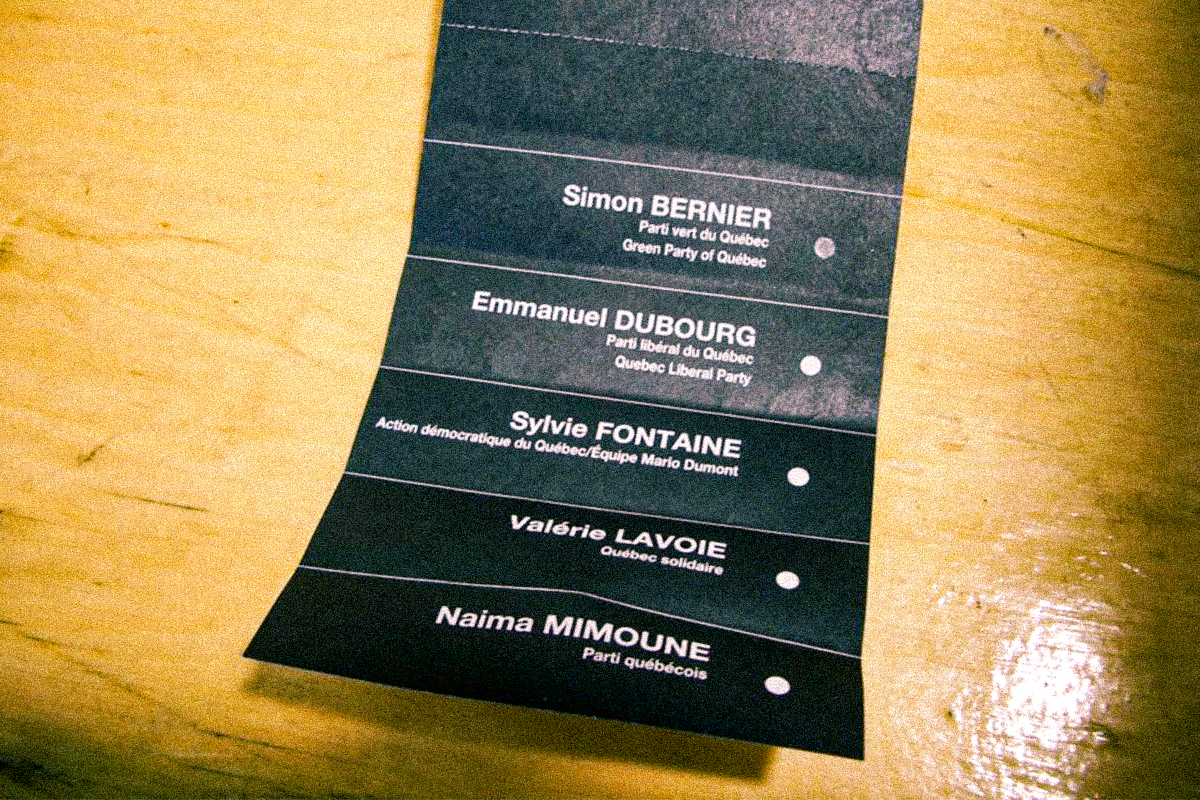

In this electoral system, people vote only for one candidate to represent their riding. In each riding, the candidate with the most votes wins that seat in parliament. The party that wins the majority of seats is called to form the government. In the event that no party has a majority, a minority government can usually last one or two years, or a coalition government is possible.

While some point to the simplicity of first-past-the-post as a strength, others complain that it allows a majority government to be elected with a minority of the votes cast.

For example, in the Oct. 3 election in Quebec, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) was re-elected with 41 per cent of the votes cast, but won 72 per cent of the seats. The Quebec Liberal Party (QLP) won 21 seats, with 14.37 per cent of the vote, while the Parti Québécois won only three seats, even though it received a higher proportion of the vote (14.61 per cent). The Conservative Party (PCQ) did not even get a seat, despite receiving almost as many votes (12.91 per cent). Québec Solidaire (QS) has half as many MPs as the PLQ, despite receiving more votes (15.43 per cent).

In the aftermath of the election, the idea of reforming the electoral system was a hot topic. Across the mainstream political spectrum, there seems to be a broad consensus that the electoral system is not working. Columnist Mathieu Bock-Côté, who flirts with the far right, agrees with Manon Massé of the left-wing QS party, who said: “This is the election of distortion. More than ever, we see how the voting system is broken in Quebec.”

Many have pointed out the undemocratic nature of an election where 41 per cent of voters choose 72 per cent of the MNAs. This is made worse when you consider that voter turnout was 66 per cent, which means that the current government was elected by only 27 per cent of registered voters. Moreover, as is often said, with a majority government able to easily out-vote other parties in parliament, and strict party discipline, a majority government is a de facto dictatorship elected for four years.

In addition, the first-past-the-post system encourages so-called “strategic voting” and discourages voters from “voting their conscience”. That is, voters will tend to vote for a party they do not really support, but which is likely to win in their riding, in order to block a party they like even less. This benefits the big establishment parties and hurts the smaller, often left-wing, parties. At the federal level, the Liberal Party makes its bread and butter from votes cast to block the Conservative Party.

All sorts of electoral models have been proposed to replace first-past-the-post, but they generally include the idea of “proportional representation”, i.e. when the number of seats won by each party is distributed according to the percentage of votes received. This is the case of the Mouvement Nouvelle Démocratie, which has launched an advertising campaign in the last few days to promote electoral reform.

This is not the first time that electoral reform has been put forward.

Referendums on the issue were held in British Columbia in 2005 and 2009, in Ontario in 2007 and in 2005 in Prince Edward Island, all of them unsuccessful. A proposal for a mixed-member proportional system won by a majority in another referendum in Prince Edward Island in 2016, but the Liberal government of Wade MacLauchlan refused to implement the result, citing the low voter turnout of 36 per cent.

During the last Quebec election campaign in 2018, the CAQ pledged, along with QS and the PQ, to adopt electoral reform if elected. Once in power, the CAQ did table a bill proposing a mixed electoral system with regional compensation, but the bill was left to languish in parliamentary limbo until the CAQ finally abandoned it. François Legault thus broke his promise to not “do what Justin Trudeau did”. Indeed, once in power, Justin Trudeau had also abandoned a promise made during the 2015 campaign to reform the voting system.

It must be said that it is very unlikely that a government will willingly agree to electoral reform. If a party wins a majority, it is almost invariably because the first-past-the-post system brought it to power. As journalist Chantal Hébert pointed out on Quebec’s recent election night, the leader of the party in power trying to pass electoral reform would have a hard time explaining to his MPs that he is asking them to adopt a law that will cause a third of them to lose their seats in the next election.

Playing with the parameters

There is no doubt that the current electoral system is not democratic. But does that mean that Marxists should support these calls for electoral reform?

On the face of it, the call for reform may seem appealing: more democracy, why not? Marxists are the first to fight for real democracy, to oppose attacks on democratic rights and to fight for any reform that can improve the ability of workers to organize, express themselves and take part in politics.

However, the case for other voting systems is not as clear as some would argue, especially from the point of view of the interests of the working class.

For example, the main argument against first-past-the-post is that it leads to “vote splitting”, when votes are distributed among several parties so that no one has a majority, allowing a party with a minority of votes to sneak in and take the majority of seats.

Many have pointed out that with 13 per cent of the vote, the Conservative Party of Quebec should be represented in the National Assembly, which a proportional system would allow. It would be difficult to find a less convincing argument in favour of proportional representation! A parliament where twenty or so CAQ MNAs would have been replaced by twenty or so PQ and Conservative MNAs would not have been any better for the workers of Quebec.

In practice, it doesn’t matter if the bourgeois government is formed out of a single majority party, as in the Canadian system, or if it is formed by a coalition of different bourgeois parties, like in Italy or Israel. The result is the same for the workers: a government that attacks their living conditions and their rights.

Proportional systems also have their disadvantages. In particular, they are not conducive to the expression of radical dissenting voices in reformist workers’ parties like the NDP or the British Labour Party. With proportional representation, voters do not vote directly for their particular representative. Instead, seats are distributed proportionally between parties according to a list drawn up by each party bureaucracy. This gives the conservative bureaucracies of reformist parties a much stronger hold on candidates. It is easy for them to make sure that no candidate who is too far to the left ends up on their lists.

In contrast, in the first-past-the-post system, the candidates put forward by each party are elected in riding nomination contests in which the party’s rank and file vote for their candidate. Although the bureaucracies of the reformist parties intervene to try to control the outcome of these elections, this opens up cracks in which left-wing candidates can insert themselves, allowing the left wing of these parties to express itself. This has been seen recently with the candidacies of socialists like Jessa McLean in the Ontario NDP and Rosalie Bélanger-Rioux in Québec Solidaire. In the same vein, it theoretically keeps MPs accountable to the membership of their ridings by giving them the right to initiate a recall vote, which is not possible with the lists drawn up by the bureaucracy. In this respect, the first-past-the-post system is slightly better than a proportional system.

As for preferential systems, where voters choose not by putting an X beside their choice but by numbering the candidates in order of preference, they also have their weaknesses. In particular, since it is very rare for a candidate to win an absolute majority of votes as a first choice, it is usually the second choices that are decisive. As an article in La Presse explains, the preferential system “forces parties to adopt a moderate, more unifying discourse in order to be the second choice of voters when they are not the first”. This has the effect of favouring the more “inoffensive” and “moderate” candidates and parties. It is therefore a system that benefits centrist and liberal politicians and protects the status quo.

Reform or revolution?

One could go on and on about the merits and demerits of each voting system. But in the end, as revolutionaries, we have better things to do than worry about the parameters by which, to paraphrase Marx, every four years we choose which member of the ruling class will “trample” the workers in parliament.

Indeed, the idea of electoral reform overlooks one small problem: it’s not just the current voting system that’s anti-democratic, it’s the whole bourgeois parliamentary system. All sorts of other voting systems are used around the world: first-past-the-post, instant run-off, multi-mandate proportional, single transferable vote, mixed system, etc. But all capitalist countries, whatever their voting system, have one thing in common: workers’ interests are not represented in parliament.

In all countries, no matter how it is elected, the government is run in the interests of the capitalist ruling class. “The modern government is merely a committee which manages the common affairs of the entire bourgeois class”, as the Communist Manifesto states.

Since its inception, parliamentarianism has functioned to manage the common affairs of the ruling class among gentlemen. Elections were for a long time the private business of property owners; it was only after hard struggles that the workers won universal suffrage.

Universal suffrage was not granted to the workers willingly, and then only on the condition that it would not allow the working class to challenge the established capitalist order. If election results did pose a threat, the ruling class would quickly override the democratic will of the workers, as they have done many times in history, from the numerous coups against democratically elected leaders in Latin America to the constitutional coup against the Australian Labour government in 1975. But more often than not, parties that try to govern in the interests of working people, in even the slightest way, are instead forced to abandon their left-wing policies by the economic and social pressure of the ruling class, as we saw with the Syriza government in Greece in 2015 or Bob Rae’s NDP government in Ontario in the 1990s.

It is not by changing the rules of the capitalist parliamentary game that we will win improvements for workers. We have to be blunt in saying that fighting for such a reform is a waste of time and effort, and often is used by bourgeois parties and the bureaucracy of the labour movement and the left-wing parties as a distraction. The PQ, for example, started making noise about the voting system after its recent electoral defeats, even though the party did nothing to change the system during its time in power. The Québec Solidaire leadership, after this election, made a big stink about the voting system, pointing out that under a proportional system, the party would have had five more MPs. As if the party’s stagnation was due to the voting system, and not to the “moderate” (read: right-wing) turn of the party leadership in recent years, which allowed the Parti Québécois to edge to the left of QS during the campaign.

Moreover, the arguments for electoral reform are devoid of any class considerations. For example, Sol Zanetti of QS, at the end of a Facebook post in favour of a mixed-member proportional system, suggested that everyone, “whatever [their] political allegiance”, should become a member of Mouvement Nouvelle Démocratie (the campaign for voting reform mentioned above). This kind of statement betrays a worldview in which politics is a gentle debate of ideas in which everyone has an equal interest in seeing all political tendencies expressed, and not a struggle between classes each with irreconcilable material interests and their own methods of struggle.

Historically, workers have won important reforms not by parliamentary methods but by the methods of class struggle, those that build on the strengths of the working class: strikes, occupations, mass demonstrations. It was mass movements that forced governments of all political leanings to introduce social programs, better wages and working conditions or other concessions to workers. Parliament can be used as a platform from which to spread socialist ideas, but we must never lose sight of the fact that it is a secondary battleground.

If we are serious about wanting a better democracy, we cannot stop at trying to change the rules of a rigged game. Under capitalism, regardless of the voting system, democracy ends where the workplace begins, where the bosses reign supreme. Instead of getting lost in a discussion about the voting system, we need to fight for a socialist revolution that can bring about real democracy: a workers’ democracy based in all workplaces, which would plan the economy democratically. This is a struggle that is well worthwhile.