In the past months, the world economy has been creeping towards a state of disarray. Shops have been running out of goods, gas stations have been running out of gas, energy prices have shot up and major western harbours have become completely clogged up with swarms of ships queuing up, sometimes having to wait weeks to unload. Just as we were told that the Covid crisis was over and that life was bouncing back to normal, the world market is feeling the drag of a series of converging crises.

From supply chains and labour markets, to the energy sector and transportation, bottlenecks have been mushrooming across the world market, leaving the strategists of capital worried and scratching their heads. Things which were taken for granted, such as the fact that a particular product will be available or produced, and furthermore that it will be delivered within a reasonable time, can no longer be taken for granted.

But ask the so-called experts and they will struggle to explain what is fundamentally happening. For them, all this appears as a peculiar concatenation of accidents, all coincidentally occurring at the same time. This goes to prove that piles of facts are of no use if you do not understand the underlying process that they reflect. The wild swings we are witnessing in the world economy expose a system which is tied up in knots, and which is incapable of responding to the needs of humanity.

Supply lines stretched

Last year we saw the first signs of the brewing crisis in the semiconductor sector. The switch to home working, increased sales of electric cars and the release of popular gaming consoles pushed microchip production to maximum capacity, leading to delays, which were particularly felt in the sales of Playstation and Xbox consoles. Back then, this was explained away as nothing but a minor, temporary hiccup in an otherwise onward-marching economy.

But it was precisely this booming economy that exacerbated the problem by leaving no spare capacity to catch up with the growing backlog in production. Hence the situation has spiralled into a serious logjam in the world market, affecting every possible industry, from mobile phones, microwave ovens and fridges to machine tools, spare parts and cars, all of which need chips to function.

Toyota, the world’s biggest car producer, has said it will cut production by 40 percent. In July, new car sales in France declined by 35 percent, while sales in Britain, Spain, Germany and Italy fell by 30, 29, 25 and 19 percent respectively, all due to a shortage of microchips. As a result of the shortage of new vehicles we have the absurd situation in places like Britain and the US, where used cars are often going for higher prices than new ones.

Other industries face similar shortages. The price of ethylene for instance, the most important petrochemical in the world, has increased by 43 percent and other plastics such as PVC and Epoxy have seen rises of 70 to 170 percent. This is because a decline in production – disrupted by the Covid-19 crisis – cannot keep up with demand, which is at record highs. Hence, things like paint are in short supply, while plastic packaging prices for food and other goods spiral upward. All of this is exacerbated when major companies, eager to secure their own supplies, start hoarding goods and putting in advanced orders, further clogging up supply chains and driving up prices.

Shipping and transportation

Even if companies manage to secure their products, getting them delivered is a different matter entirely. All freight ships going from China to Europe – the most important shipping route in the world – are booked months and weeks ahead with little to no spare capacity. The demand for shipping along these routes is so high that ports are being overwhelmed.

An unprecedented number of large container ships – almost 500 – are waiting to dock at ports in Asia, Europe and North America and some of them have to wait up to two weeks to unload. All of this is pushing up shipping costs, which stand at four to five times the price of a year ago. One month ago, the rush to secure Christmas deliveries pushed the price up to about ten times that of a year ago.

In the past year and a half, capacity in shipping has been hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, and a series of accidents such as the blocking of the Suez Canal by the container ship Ever Given. At the same time, demand has exploded as a result of a spending boom in the west. Seeing the bottlenecks spreading like ripples over water, big companies try to secure as many goods and as much shipping capacity as possible, making life harder for smaller companies.

Shipping companies are in turn downgrading their services for routes to and from Africa and Latin America, as well as the route from the West back to China, focusing on the most profitable routes from China to Europe and the US. Thus, the total amount of containers on the market is further reduced, exacerbating the disproportion between supply and demand, and adding to the inflationary forces at play.

Labour shortages

Even beyond shipping, the transport sector is struggling to keep up with the market. Along with unprecedented demand, there is a shortage of labour. In the EU and in Britain for instance, there is a shortage of 500,000 and 100,000 lorry drivers respectively.

Covid-19 led to a huge shift toward online shopping, meaning a rise in demand for truck drivers and other transport related jobs. However, coming on top of years of declining wages and worsening working conditions, many people are not very keen to take on these jobs. And in Britain, the impact of Brexit has led to a shortfall of the European workers who make up a big chunk of this workforce.

In fact, due to the enormous strains put on these workers during the pandemic, many have left the industry altogether, helped by the fact that furlough money and other state benefits are often higher than the meagre wages of truck drivers. Now some bosses are trying to lure workers with promises of higher wages, but due to the lack of licenced drivers, that will take some time to filter through. This situation was further aggravated by the lack of tests for Heavy Good Vehicle licences during the pandemic. In other fields, such as retail, and agriculture, similar processes have occurred amongst low-paid workers.

At the other end of the spectrum, millions of white-collar jobs also remain unoccupied due to a booming demand and a lack of qualified personnel. All of this means that while some sectors, such as hospitality, have been dealing with rising unemployment, other sectors are experiencing a shortage of labour, which is causing serious problems across the economy. In the US alone, 5 million jobs remain vacant, while the figure in Britain is 1 million. The labour shortage in turn has a knock on effect on supply lines and shipping.

Energy crisis

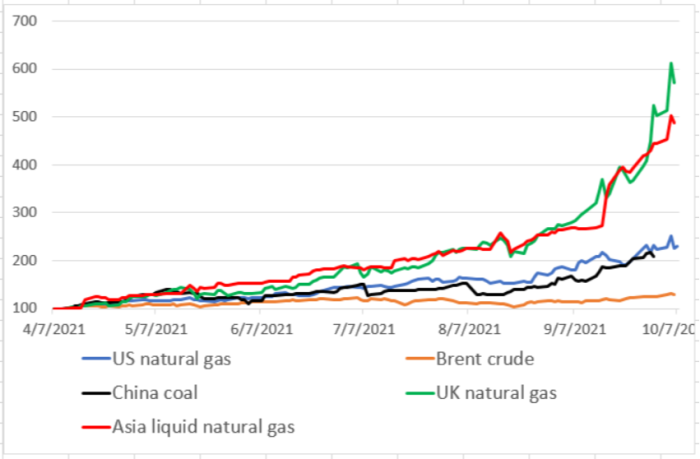

The rebound of the economy from the ebb during the height of the pandemic has also had a big impact on the energy sector. As factories, ships and shops are running on full blast, oil, gas and coal prices have been rising. Since January, the price of Brent crude oil has more than doubled to a three-year high at $83.67 per barrel. Coal prices have also soared, leading to power cuts and disruption in more than half of all production facilities in China.

The pattern by now should be familiar: coal supply has been limited or disrupted due to external factors such as Covid-19 related measures in mines, a trade war between China and Australia, as well as attempts by governments to decrease reliance on fossil fuels. In the meantime, demand has shot up, pushing prices up.

Once the process started, new factors came into play. The Chinese state declared that it would spare no resources to secure coal for production, leading to a scramble to secure coal both by producers and speculators alike.

The search for cheaper alternatives to coal powered electricity – particularly in Asia – then led to rising natural gas prices, just as Europe was witnessing very low gas reserves going into winter. Consequently, gas prices have exploded, with bulk prices reaching almost €116 per megawatt hour last week, compared with €16 in early January. The fact that large amounts of oil, coal and natural gas are stuck on containerships on the world’s oceans adds an additional problem feeding into the same general trend: rising prices and shortages.

Inflation

All of the above is gradually spilling over into prices, which are rising across the board. Inflation in Britain has gone from below 1% earlier this year to 3.2% in August, the highest in 10 years. In the US, the PCE measure of inflation, which excludes food and energy, rose by 3.62% compared to a year ago. That is the highest figure since 1991. In the EU, inflation has reached 3.4%, the highest level for 13 years. These are still relatively low figures historically, but the potential is there for matters to get worse. In Europe, energy inflation this year stands at 17 percent, with gas prices set to rise by up to 30 percent this winter. In other sectors, price hikes will take longer to filter through, but they are coming. This will have a profound impact on the class struggle.

After almost two years of mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic, the legitimacy of the establishment is at an all-time low. During that period, the working class held its head down and accepted what was coming. But now society is opening up, labour is in demand, and inflation is quickly eating into wages and living conditions. This is a finished recipe for class struggle.

Already, there are signs of a slight increase in strikes. In the US, tens of thousands of workers have either taken strike action or voted for strike, including the Washington state carpenters, health and education workers, workers at John Deere and Kellog’s, etc. In Britain, the ranks of Unite and GMB unions have overwhelmingly rejected a 1.75% pay rise for council staff in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and are now balloting workers for strike action. In Germany, where inflation has reached 4.1%, several sectors are putting in bold pay claims and threatening strike action, including the threat of a national strike of construction workers.

As the situation worsens, other layers will join in in order to defend their living standards. The ruling class is clearly worried about the potential for such developments. One Tory MP, David Morris, warned of a new “winter of discontent” like in the ‘70s, with mass wildcat strikes and social unrest. We should remember that the winter of discontent in Britain occurred precisely after an inflationary shock caused by the oil crisis, with oil prices shooting up and leading to generalised inflation across the board.

Accident or necessity?

Wherever you look, there is a crisis brewing and each crisis feeds into the other, building towards what could potentially become a perfect storm, with dramatic consequences. For the most part, the bourgeois commentators do not understand any of what is going on. Everywhere, they see nothing but a series of unfortunate events; a butterfly effect of colossal proportions, with accident upon accident leading to the shortages and bottlenecks that are rocking the world market. Why so many accidents happen at the same time and in such different spheres however, they cannot explain.

But there is a clear trend underlying all of this. The Covid-19 pandemic dislocated the whole of society. Habits changed, consumption changed and production changed. Spending on tourism and transport, for instance, declined massively, whereas products such as computers, home decoration and fridges were in higher demand. The move to online shopping was accelerated whereas physical services stagnated. This meant that the pressure was increased on certain parts of the world economy.

Meanwhile, production in general was severely restricted due to the pandemic. Factories, mines and ports were temporarily shut, or operated at limited capacity. In many parts of the world, they still do.

Faced with this situation, the ruling classes, intent on avoiding a deeper crisis and the potential social backlash of such a crisis, released a series of large economic stimulus packages. In the US alone, $9.5 trillion worth of stimulus was pumped into the economy, much of it straight into the hands of ordinary working class people, who for the most part spent it on ordinary consumer goods. Most other governments followed a similar line. But as we explained at the time, you cannot work your way out of a crisis by printing money.

Where production is restricted and money is poured into the system, the inevitable result is a situation where demand outstrips supply, creating enormous inflationary pressure. That is exactly what is happening. Demand for consumer goods, albeit an artificial demand created by the ruling class, has never been as high as it is today. In such a charged situation, with the pressure on the most sought-after products reaching its highest point, any accident can become a serious bottleneck, bringing the underlying contradictions to the surface.

This was a crisis that was waiting to happen. With the vast majority of companies now working according to ‘just-in-time’ production, any shock like this will immediately send ripples throughout the whole economy. For decades, the bourgeois have been squeezing profits out of minimising their stocks, and maximising their capital circulation: now that is turning into its opposite. Thus, hoarding has suddenly become the new trend. Rushing to secure their stocks well into the future, big companies such as Walmart, Apple and Target have put in huge advance orders and reserved shipping capacity, thereby adding to the general crisis.

Economic nationalism

All of this is compounded by the rise of economic nationalism. Last year, China imposed an import ban on Australian coal. This has had a significant impact on driving up coal prices worldwide. The US is now putting increasing pressure on the EU not to finish the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline going from Russia to Europe, even though it would alleviate some of the pressure on gas prices in Europe. Vladimir Putin, on the other hand, is using the present crisis to expedite legal approval of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, even though he could quickly alleviate Europe’s problems via alternative pipelines. Likewise, Brexit has dramatically worsened the impact of the present crisis on Britain – a crisis which is threatening to push Britain into a recession.

As general insecurity rises, more and more companies are thinking twice about relying on international trade. Many European companies are looking to move production to Turkey or Eastern Europe, which would be closer to home and less affected by sudden shocks, transport crises and trade wars. Seeing their overreliance on Asian chip manufacturers, China, the EU and the US are all building semiconductor production plants.

In Korea, the chip shortage does not seem to be affecting Korean automakers as much as American ones, which implies that Korean chip manufacturers are giving preferential treatment to domestic companies. In China, the state is pulling out all the stops to secure coal for its power plants. The longer the shortages continue, the more the question of hoarding and securing production will become a national matter, with the ruling classes of each country rushing to defend their own position. All over the world, the general crisis of the system is leading to increased tension between nations. This is now threatening the whole of the fragile web of world trade, which was the fundamental driving force of growth in the whole of the past period.

Blind market forces

As the crisis develops, the jubilant mood of the stock markets, hot off the stimulus bonanza, is slowly giving way to a more cautious attitude. On the basis of the shortages and bottlenecks in the market, the IMF has said that it will downgrade its forecast for world economic growth. The Financial Times ran an editorial warning central banks to “be alert to stagflation” (the dangerous combination of economic decline along with persistent inflation).

Such a perspective is not certain, but it clearly is a possibility. There is a colossal amount of toxic material in the world economy. From enormous public debts ($28 trillion in the case of the US alone) and private debts, to bubbles on the stock and housing markets, any big shock or default could set off a domino effect causing the whole of the economic system into a downward spiral.

But what is the solution from a capitalist point of view? From rising inflation, rising interest rates will necessarily follow. But raising interest rates would risk pushing the world economy into a depression. Thousands of ‘zombie’ companies, worth trillions of dollars in the west, are completely dependent on cheap credit to stay afloat. The same applies to hundreds of millions of households, in particular in the west, who can only stay in their houses on the basis of near-zero interest rates. Each rise in interest rates pushes these layers closer to bankruptcy.

But keeping the gate of cheap credit and economic stimuli open would worsen the situation we see today, leading to even higher inflation; furthermore, it would end in a recession regardless. On the basis of the present system, there is no solution. Humanity is left to the mercy of blind forces of the market, which pay no attention to the wellbeing of society as a whole.

But wasn’t the market supposed to regulate itself and create the best of all possible worlds? Quite the opposite. Capitalism is incapable of adjusting and reacting to major shocks. In a situation like today, the market forces are exacerbating matters, deepening the contradictions that are building up. This fact was recognised by Takeshi Hashimoto, president of the Mitsui OSK Lines container ship company, who told the Financial Times that:

“If left entirely to the market economy, individual companies and individuals all doing their utmost to find the best solution for themselves will result in more and more turmoil and an out-of-control situation…”

As always happens, when circumstances get serious, the capitalists are forced to admit the limits of their system. In fact, in Britain, the ruling class has had to introduce elements of planning, by temporarily suspending competition laws to allow major retailers to collaborate to alleviate the goods shortages. The same goes for the resupply of fuel to petrol stations, which is now organised on a collective basis between the major companies and even the army having to be drafted in to refuel stations.

Capitalism is an anarchic system. It is based on private property and competition for profit. However much the individual capitalist might want to solve the problems of society, his primary purpose is to follow his own private interests. Such a system is incapable of dealing with the problems facing humanity. It is precisely here that it becomes clearer than ever that it stands in direct opposition to the interests of ordinary working people; and that in order for society to thrive, capitalism must be overthrown.