Over 100,000 people died last year from drug overdoses in the US. It was the second year in a row that the death toll exceeded that figure, according to statistics from the CDC. These overdoses are disproportionately concentrated in poor regions, particularly Appalachia, which has been ravaged by an opioid addiction crisis for the past two and a half decades.

Recent lawsuits against the billionaire Sackler family—the owners of Purdue Pharma and producers of OxyContin—have brought to light the active role their company played in creating this crisis. At one of the court hearings that took place earlier this year, victims of the opioid epidemic who had lost their loved ones confronted the Sacklers to their face. CEO Richard Sackler and the other executives stared blankly as one mother played the recording of the 911 phone call she made the night she found her son dead from an overdose:

“I understand today’s your birthday, Richard, how will you be celebrating?” she said, noting that her son would have been turning 34 soon. “I guarantee it won’t be in the cemetery… You have truly benefited from the death of children. You are scum of the earth.”

With this comment, Sackler, who was turning 77 that day, was reminded of his own words in a leaked email, in which he had disparagingly referred to people with addictions as “the scum of the earth.” The family and their associates have indeed made billions of dollars from the deaths of hundreds of thousands of American workers. Their willful destruction of countless lives and families across the country for the sake of profit is one of the starkest examples of capitalism’s toll on humanity.

The myth of the “addiction proof” opioid

In 1995, Purdue Pharma applied for FDA approval of a “revolutionary” new drug—OxyContin, an opioid painkiller with an extended release coating which allegedly made it “addiction proof.” According to Purdue, the extended release formula meant that patients would experience a constant low dose of pain relief, instead of the sudden peaks and drop-offs traditionally associated with opioid medication and addiction.

FDA approval came and OxyContin was released the next year. From the very beginning, Purdue put profits above all else, blatantly lying about the addictive potential of OxyContin in the original FDA-approved package insert. It claimed that “patients receiving doses of 20–60 mg/day can usually have the therapy stopped abruptly without incident,” even though Purdue’s own pre-release clinical trials resulted in 28% of patients experiencing withdrawal symptoms after taking low doses of the drug.

The insert also stated, “delayed absorption, as provided by OxyContin tablets, is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug.” Neither Purdue nor the FDA had any evidence to back up this statement. In fact, within months of OxyContin’s release, the company became aware of widespread addiction to their morphine painkiller MS Contin, despite its extended release coating. Purdue had every reason to believe OxyContin would produce similar results, but they continued to distribute it anyway because they knew it would be an extremely profitable drug.

One of the most insidious deceptions during this period was Purdue’s claim that OxyContin only needed to be taken every 12 hours, allowing them to market the pill as a convenient twice-a-day medication. Their advertisements from this period promised that “effective relief takes just two.” In reality, OxyContin’s effects typically last for around eight hours, a discrepancy which is a perfect recipe for addiction. Once patients get to the eight-hour mark, they experience hours of excruciating opioid withdrawal which is only relieved by their next dose, creating the withdrawal-euphoria cycle that fuels addiction. These short withdrawals can also cause patients to seek out higher and higher doses, increasing the chance of overdose.

All of this was known to Purdue at the time. Another of their own pre-release clinical trials showed that about 50% of patients needed the drug more frequently than twice a day, and the company almost immediately started getting reports from doctors, patients, and sales reps that more frequent dosage was needed. Still, they continued to market the drug as having a twelve-hour lifespan.

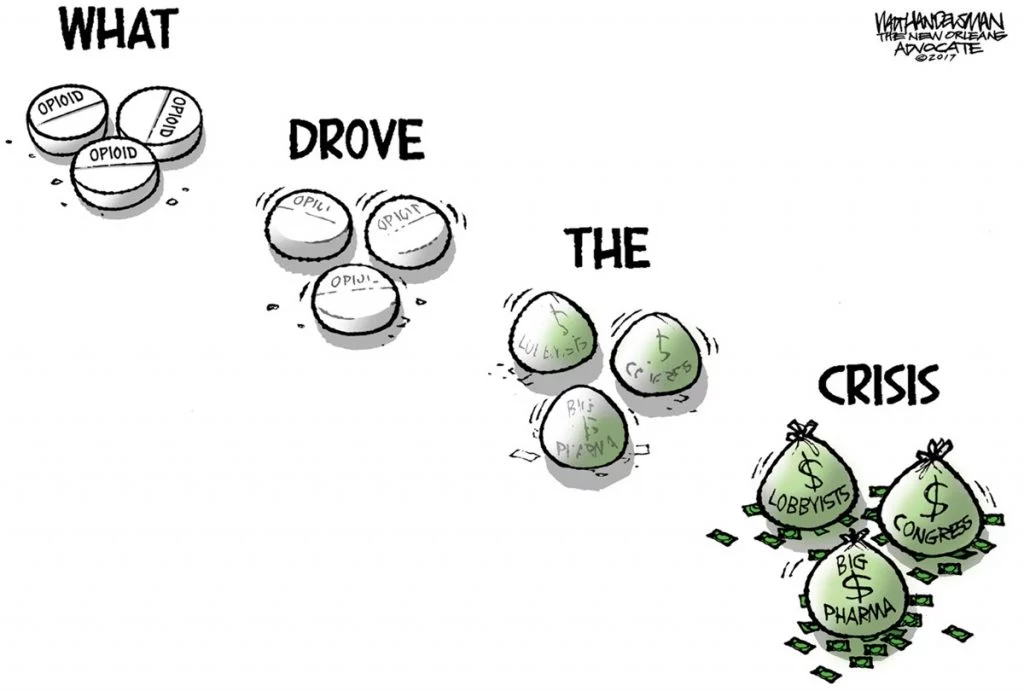

Despite all these discrepancies and unproven claims, FDA approval came as a result of corruption and direct ties between Purdue and the government agencies tasked with regulating production and distribution of pharmaceuticals. Nine months before the drug was officially approved, internal Purdue communications showed that the FDA official overseeing the application, Curtis Wright, had already guaranteed approval to the company. Just over a year later, Wright started working for Purdue with a starting salary of $400,000 a year. Between 2006 and 2015, opioid manufacturers as a whole spent over $700 million lobbying federal and state governments, and Richard Sackler once boasted that Purdue could “get virtually every senator or congressman we want to talk to on the phone in the next 72 hours.”

An aggressive marketing scheme

After receiving the FDA’s rubber stamp, Purdue trained a team of sales reps to convince doctors of OxyContin’s safety and convenience. The company targeted doctors that they labeled “opioid naive”: physicians who shied away from morphine because of its reputation as highly addictive, but were unfamiliar with OxyContin’s active ingredient, the semi-synthetic opioid oxycodone. These tended to be doctors in poor areas of the country, particularly Appalachia. These areas also have high rates of chronic pain due to the prevalence of manual labor, chronic illness, and lack of access to quality healthcare. Doctors in these regions were desperate to help their patients with convenient, long-term pain treatment that didn’t rely on morphine. OxyContin appeared to be the miracle drug they had been waiting for.

Sales reps aggressively marketed to these “opioid naive” doctors, but conveniently left out the fact that oxycodone is in fact twice as powerful as morphine, and that the pills could be crushed, chewed, or dissolved to override the extended release coating. Instead, they used the FDA-approved language in the package insert to reassure doctors that OxyContin’s formula made it safe and that their patients wouldn’t become addicted.

Purdue amassed huge amounts of sales data during this time which clearly showed the existence of widespread addiction and black market distribution. Certain areas were buying volumes of pills completely out of proportion to the size of their populations, often with more prescriptions than people. The company also received many reports from sales reps about addictions and deaths across the country.

Instead of recognizing and attempting to curb the unfolding crisis, Purdue harnessed this data to generate even more profit by further honing their distribution and marketing strategy. They identified and targeted areas with high prescription rates, sending additional reps and incentivized them with huge bonuses based on the number of pills sold. This targeting caused the epidemic to spread like wildfire through Appalachia. In Kentucky, the drug overdose death rate rose from 4.9 per 100,000 in 1999, to 15.3 in 2005, to 29.9 in 2015.

Pill mills also began to crop up: practices which prescribed huge quantities of opioids to people who then resold these pills illegally and gave the prescribing doctors a portion of their profits. Purdue’s sales data identified many such practices, and the company was even notified of some of them by local police, but they continued to sell pills to them anyway.

Lobbyists of the “pain care movement”

Calculated marketing wasn’t Purdue’s only weapon. The company also used its enormous bank accounts to influence the medical field and public opinion. Between 1996 and 2001, Purdue sponsored over 7,000 “pain management seminars.” Doctors from across the country were sent to these all-expenses-paid conferences in resort locations to hear from pain experts who were paid to speak on the benefits of opioids. The company advertised heavily in medical journals, and funded and wrote studies that got published in several of them.

The medical narrative developed by Purdue in these conferences and articles was the idea of “pseudo-addiction.” This “theory” claims that when patients request more frequent and higher doses of painkillers, they are not truly addicted, but simply have increased underlying pain that doctors have the responsibility to treat with more painkillers. This concept has since been entirely discredited by the medical community.

Purdue also teamed up with doctors and others in the industry to create and fund what appeared to be independent organizations that advocated on behalf of the “pain care movement” to promote prescription painkillers. One of the more prominent coalitions, the Pain Care Forum, was headed by a Purdue lobbyist and executive. The American Pain Foundation published a book, sponsored by Purdue, aimed at promoting opioids as a pain management solution for veterans. Sales reps brought these resources to their meetings with doctors, using the supposed “independence” of these “advocacy groups” to legitimize their claims of OxyContin’s safety.

Purdue and the Sacklers also had ties to the very institutions training new generations of doctors on how to treat chronic pain. At Tufts University, long-time Purdue president Richard Sackler sat on the School of Medicine advisory board for 18 years. Since 1980, the Sacklers have donated more than $15 million to the school. In 1999, Purdue agreed to a recurring annual donation of $330,000 with the specific purpose of funding a new master’s program: Pain Research, Education, and Policy. The head of the program, Dr. Daniel Carr, appeared in a Purdue advertisement, and another professor in the program, Dr. David Haddox, worked directly for Purdue as a pain specialist and was a main developer of the idea of “pseudo-addiction.” He taught this concept to a generation of Tufts medical students specializing in pain relief, even using Purdue branded materials in his coursework.

The company’s influence in the medical field also found its way into public opinion through the media. For example, a 2004 New York Times opinion piece shifted the blame for addiction onto patients, stating that “when you scratch the surface of someone who is addicted to painkillers, you usually find a seasoned drug abuser.” The author cites a study written by Purdue scientists published in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology to back up this claim. The author herself ran a conservative think tank which received $15,000 a year from Purdue, and she sent the piece to the company for approval before publishing.

Under capitalism, research and educational institutions rely on funding from wealthy donors and private companies. As such, these supposedly “neutral” institutions are frequently influenced by the profit motive, both consciously and unconsciously. Purdue was able to use its influence in the medical industry to promote the idea of “pseudo-addiction” and distort the understanding of pain management to the company’s advantage, turning many doctors into unwilling participants in this crisis.

The deadly results

In 2010, when Purdue’s patent on OxyContin was about to expire and they would soon have to compete with generic versions, the company had a sudden change of heart. Purdue admitted to the FDA that OxyContin was addictive and dangerous, and asked the agency not to approve any applications for generic versions because of this risk to public health. They simultaneously released OxyContin OP, a new version of the drug with an extended release coating that couldn’t be crushed or dissolved. The FDA approved OxyContin OP and agreed not to approve any generic versions of the original OxyContin, ensuring that Purdue would continue to have a monopoly on oxycodone painkillers.

However, by 2010 the pharmaceutical industry had caused millions of Americans to become addicted to opioids. Rather than curbing the opioid epidemic, the withdrawal of the original OxyContin from the market only made matters worse. When this source of opioids disappeared, people began using other illegal opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl. In 2016, about 80% of new heroin users’ addictions had started with prescription painkillers. These unregulated drugs are easier to overdose on than prescription painkillers because of their inconsistent strength and ingredients. All of this has led to a rise in opioid deaths over the past decade. To date, over 600,000 people in the US have died of opioid overdoses.

While the release of OxyContin marked a turning point in the prescription painkiller industry, and Purdue introduced many insidious marketing techniques and medical ideas, this ruthless pursuit of profit at the expense of human life is not unique to Purdue. The industry’s entire supply chain—from the growers cultivating opium poppy, to the pharmacies distributing pills to patients—knowingly profited off of this crisis.

Johnson & Johnson grows opium poppy and supplies opioid manufacturers with many of the active compounds used in their drugs. They used many of the same tactics as Purdue over the past few decades to increase opioid use across the country: marketing these drugs as safe and non-addictive, using sales data to target doctors already prescribing high amounts of opioids (including pill mills), funding “independent” pain advocacy groups, and lobbying government officials to make decisions favorable to the industry. Drug distributors continued shipping opioids to areas with disproportionally high orders, and Walgreens, Walmart, and CVS watched and did nothing as enormous quantities of prescriptions and pills passed through their pharmacies.

The incentive for production under capitalism is to generate profit for owners and shareholders. In order to do so, businesses must take whatever measures are necessary to outcompete each other and expand their customer base, with no regard for how these decisions affect the lives of ordinary people. The history of Purdue and OxyContin is therefore not an isolated incident or the mere result of a particularly greedy group of capitalists. This deadly crisis is the direct result of capitalism, a system based on private ownership of the means of production and driven by the profit motive.

No solution under capitalism: nationalize Big Pharma!

Since becoming more prominent in the public eye, many proposed solutions to the opioid crisis are being discussed. Some cities have launched programs to make addiction safer—such as methadone clinics and safe injection sites, and increasing the availability of the overdose prevention drug naloxone. While these solutions offer temporary relief from the symptoms of opioid addiction and reduce the risk of overdose, they do nothing to permanently end addiction or prevent the rise of new addictions.

Most attention has been focused on legal proceedings against the Sackler family and other big players in the pharmaceutical industry, such as Johnson & Johnson. Lawsuits against the Sacklers have been filed by all 50 states and many American Indian tribes, encompassing thousands of individual complaints from those affected by the crisis. The family, with a net worth of $11 billion, has thoroughly exploited all possible legal loopholes to avoid being held responsible. Most recently, they agreed to pay out $6 billion to several states in a civil lawsuit. In exchange, the family could not be held liable for any remaining or future civil lawsuits, leaving them free to live their lives with their remaining billions.

The capitalist courts also can’t fix the underlying problem, which is rooted in the very nature of capitalism. The profit motive drives every aspect of this crisis: from the production, distribution, and prescription of the painkillers; to the backbreaking working conditions giving people chronic pain; to the lack of access to treatment and support for those who become addicted. The only real solution to this crisis is to nationalize the pharmaceutical and all other medical industries under democratic workers’ control, integrated into an economy planned around human need, not profitability.

If painkillers were developed and distributed solely for their immediate medical purpose, there would be no need to entice people through false advertising. Research and education should be publicly funded and controlled, freed from the influence of capitalists, and pursued in the interest of humanity. This would allow doctors to make decisions based on actual medical need, not ad campaigns or research funded by companies standing to gain billions.

Improved working conditions, a shorter work week of 20 hours or less, voluntary retirement at age 55, and free access to quality healthcare would reduce the number of people experiencing chronic pain in the first place. In addition to better healthcare, more time to spend on health in general would open up the option of pain management programs that don’t rely on painkillers, such as physical therapy. For cases in which people truly need painkillers, health professionals could educate them on the potential risks and how to healthily withdraw, be in frequent contact with their patients, and provide resources to address any addictions that did arise.

Additionally, risk factors for opioid addiction include poverty, unemployment, criminal history, mental illness, and “stressful circumstances.” In a society where everyone has access to healthcare, housing, employment, nutrition, education, and time to spend with friends and family and pursue their interests, these environmental pressures would quickly disappear.

The entire logic of capitalism always puts profit over human need. From the Covid-19 pandemic to climate change, we’ve seen countless examples of this in recent years. A socialist transformation of society is the only viable solution to end the opioid epidemic and other horrors caused by this system.

Much of the information in this article was sourced from Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain and Sam Quinones’s Dreamland.