Many people believe that revolution is something alien to Canada. But in 1983, British Columbia was on the verge of revolution. The movement known as Operation Solidarity brought the province to the doorstep of a general strike and had the capitalists shaking in their boots. This was one of the most incredible uprisings of the working class in Canadian history.

An age of capitalist crisis

The backdrop to the tumultuous events of 1983 was the deep crisis that followed the postwar boom. Inflation was rampant and prices doubled from 1973-1981. In 1981, the Canadian economy was hit with the worst recession since the Great Depression. One in five manufacturing jobs disappeared and unemployment rose to 13.1 per cent.

The largely resource-based economy of British Columbia was hit particularly hard as low commodity prices for metals, timber, and coal led to massive plant shutdowns. Forestry multinationals abandoned the province in search of cheaper labour elsewhere. The result was that in 1982, the GDP of the province fell by 6.1 per cent. Unemployment shot up as hundreds of thousands found themselves without a job. Government finances dried up as tax revenue and resource royalties fell drastically.

All around the world, capitalist governments faced a similar situation. Capitalism could no longer afford the postwar reforms and a growing segment of capitalist politicians promoted slashing public services and attacking unions in order to restore profitability. Margaret Thatcher in the U.K., Ronald Reagan in the U.S., and then Brian Mulroney in Canada were all part of this movement. In British Columbia, the figurehead of this movement was a man named Bill Bennett and his party was the Social Credit party (Socreds).

The Fraser Institute, a libertarian think tank funded by millionaires, led the ideological offensive in B.C. For years they had lobbied governments to cut social services and deregulate the economy as a purported way to attract investment back to the province. This was music to Bennett’s ears and he was more than eager to implement this program.

Black Thursday

On July 7, 1983, a day that became known as “Black Thursday,” Bennett released a budgetary package containing 26 bills. This budget proposed reducing the size of the provincial public service by 15 per cent—from 46,806 to 39,965 in 1983, and again to 35,410 by 1984-85.

The bills also targeted the unions in order to mollify resistance to their agenda. Bill 2 stripped the trade unions of their right to negotiate anything other than wages. Bill 11 limited public-sector wage increases. Bill 3 strengthened the government’s ability to fire any of its 220,000 public employees without cause.

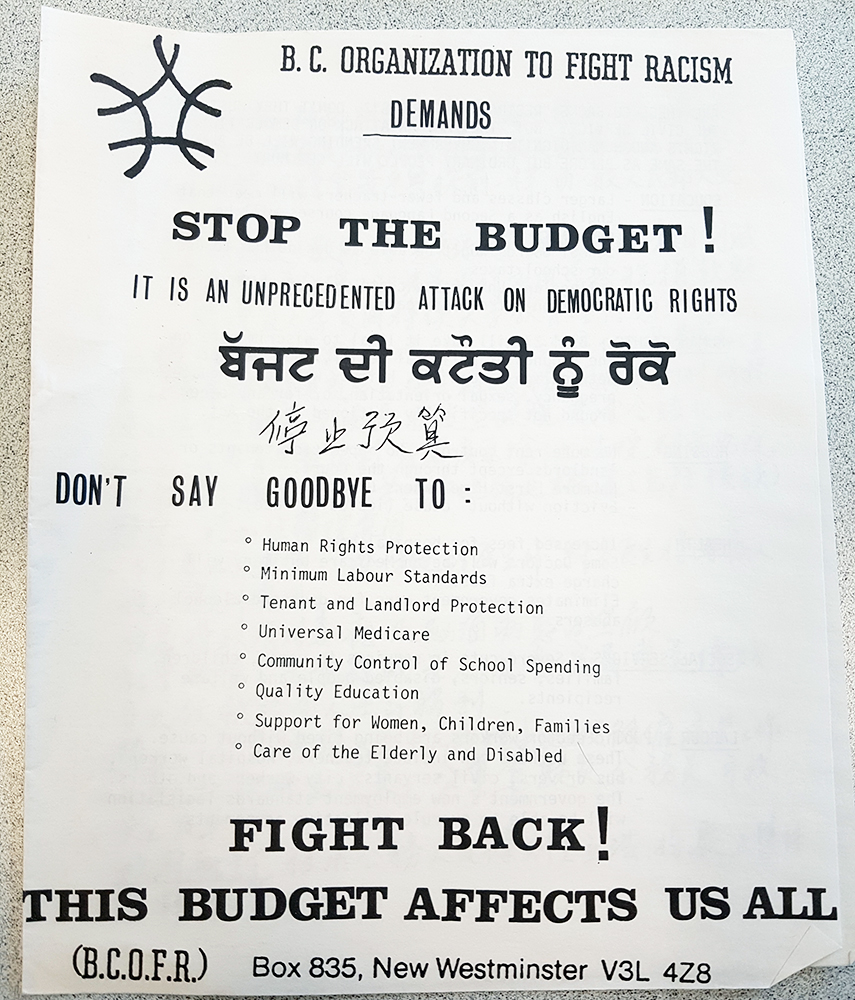

But these bills were so broad in scope they went well beyond the trade unions, attacking nearly every program which made life bearable. John Fryer, president of the National Union of Provincial Government Employees (NUPGE), summed up what the budget represented: “It’s not just the trade unionists, it’s the women, it’s the poor, it’s the elderly, it’s the sick, its minorities – nobody that is in a disadvantaged position in our society has been missed by this government’s attack.”

Bill 5 eliminated the Rentalsman office and scrapped rent controls. Bill 27 repealed the Human Rights Code, abolished the Human Rights Commission, restricted the definition of discrimination, and lowered the amount of compensation one would receive if they were found to have had their human rights violated. On budget day, the Human Rights Branch and the Human Rights Commission were closed.

Bill 24 allowed doctors to charge patients directly for services. Access to legal aid was curtailed. A weekly $50 Community Involvement Program for disabled people was suddenly terminated. Domestic violence shelters had their budgets slashed.

Showing that the government meant business, the day following the budget’s announcement, 1,600 provincial employees were given layoff notices.

But these attacks were not the product of a couple of crazy politicians. As Stan Persky, the chief editor of the Solidarity Times, explained, Bennett was “carrying out the program of very powerful organizations in British Columbia.” Persky continued:

There’s no mystery about who these organizations are. They’re the B.C. Employers Council, they’re the B.C. Chamber of Commerce, they’re the Federation of Independent Businessmen B.C. Branch, the Vancouver Stock Exchange, the Board of Trade, and the list goes on and on, including landlord’s associations, the Association of Automobile Dealers, every two-bit contractor who doesn’t want a union worker on the job. That’s an organized force in society…

In essence, what the working class of B.C. was up against was a coordinated attack by the entire bourgeoisie.

How loyally this program followed the dictates of the Fraser Institute shocked even Michael Walker, head of the institute, who stated: “Nobody was more surprised than I to discover that almost all of the main issues I raised were addressed in the Restraint Program.”

Phase 1: Working-class backlash

This budget threw gasoline on the fire. Hundreds of thousands of normally apolitical people started to organize. Throughout the province, groups of all types started to form.

The trade unions sprung into action. The day after the budget was tabled, the Lower Mainland Budget Coalition (LMBC), representing 50 unions committed to fighting against the budget, was formed. A week later, the B.C. Federation of Labour (BCFED) launched “Operation Solidarity” to mobilize the trade unions.

This was a coalition the likes of which was unheard of in the history of the province. All in all, the unions represented 400,000 workers. At the head of it was the recently crowned BCFED president Art Kube. Other key leaders were Cliff Andstein, chief negotiator for the B.C. General Employees Union (BCGEU), and Jack Munro, president of the Canadian chapter of the International Woodworkers of America (IWWA). As some of the key labour leaders in the province, these figures were the natural leaders of such a movement and would play a pivotal role.

But as the attacks were so broad, the movement was not limited to the traditional left and the trade unions. Various layers of society not usually involved in anti-governmental politics suddenly became politically active. Groups like Women Against the Budget and Chinese Canadians for the Restoration of Human Rights played a prominent role. Even members of the clergy were drawn into the movement, denouncing the cruelty of the government. On Aug. 3, the Solidarity Coalition was formed to unite all of these disparate organizations. All in all, delegates from around 200 organizations representing close to 1 million British Columbians came together.

Workers all over began to take matters into their own hands. For example, 600 employees at the Tranquille Centre for the Handicapped in Kelowna occupied the centre on July 19. Describing the events, the B.C. Labour Heritage Centre writes: “A hand-painted union flag was raised, locks were changed, managers evicted, and workers took control of the facility. All services were maintained, including a fire department and maintenance. The workers elected a council, with representatives from each shift who made decisions democratically.”

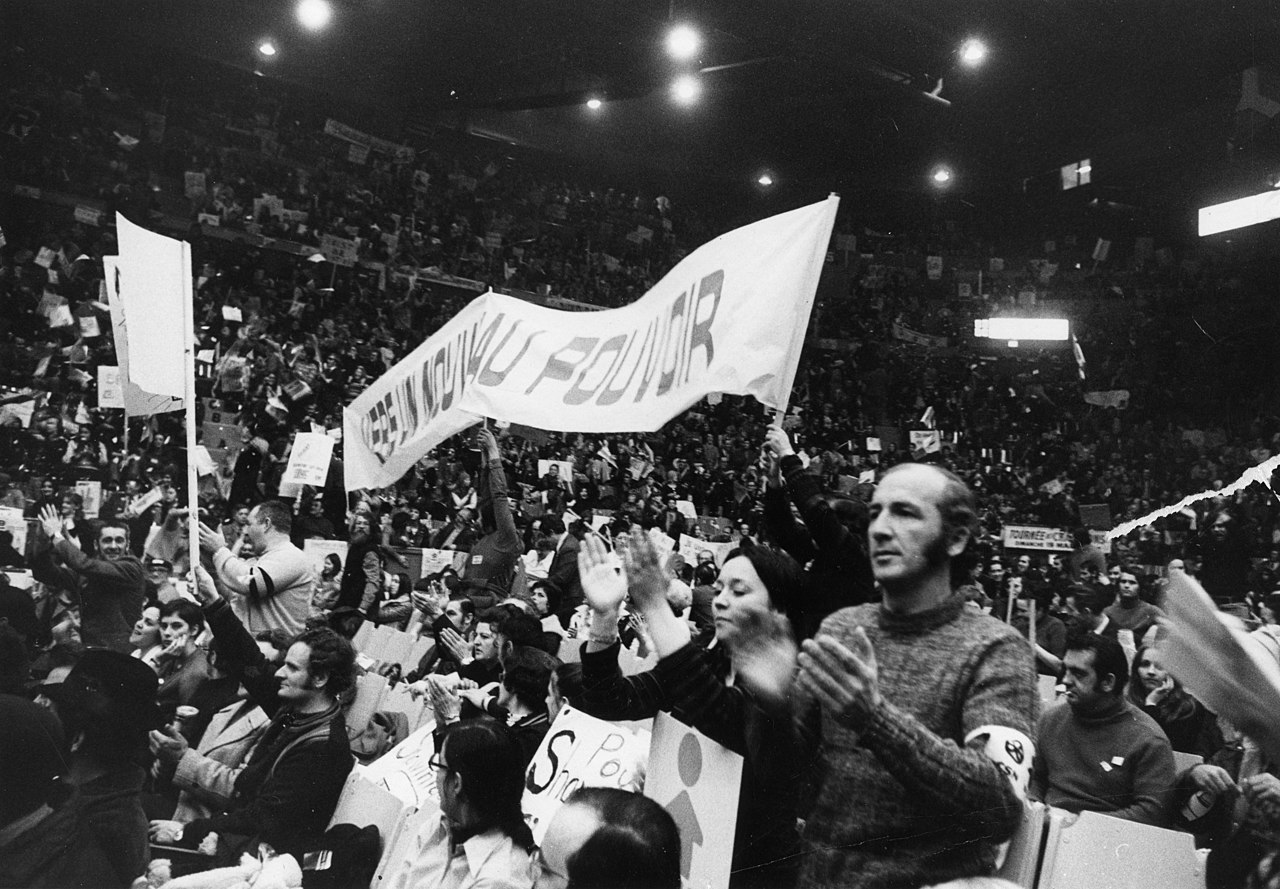

The province was constantly rocked by protests. On July 19, 6,000 people gathered at Memorial Arena in Victoria. On July 23, more than 30,000 rallied at BC Place in Vancouver. On July 27, 25,000 people protested on the lawn of the legislature in Victoria with tens of thousands demonstrating in towns all over the province. Protests drew out hundreds and thousands at government offices and town centres in communities like Nelson, Prince George, Kamloops, Kelowna, Williams Lake, Quesnel, Fort St. John, and Dawson Creek. Even in the tiny hamlet of Usk, in northwestern B.C., 20 people protested by blocking access to the ferry.

B.C. was in a state of turmoil. Protests were popping up everywhere and showed little sign of relenting.

On August 10, 50,000 people packed into the Empire Stadium in Vancouver. Public-sector workers walked off the job in a wildcat strike and in solidarity bus drivers did the same, encircling the stadium with their buses. The firefighters marched into the stadium with their marching band to cheers from the crowd.

Militant speeches were made by labour leaders and representatives from all of the various groups, denouncing the heinous program of the government. Speaker after speaker, representing groups of all different types, were united in their struggle against Bennett. The mood of the masses was confident and defiant as they felt the wind in their sails.

Phase 2: De-escalation

The undeniable momentum and the energy exhibited by the masses shocked many people who had never seen anything like this before. However, while rank-and-file workers were elated at the collective power that they now felt, not everyone was happy.

Trade union leaders were shocked, but not in a good way. Many of these leaders had built their careers negotiating deals at the bargaining table. But the workers were not looking to negotiate with the government—they wanted change now.

Incidentally, the Socreds also did not care for negotiating. Bennett did not seem to care in the slightest what the opinion of the working class was and sought to simply ram through this program. The capitalists needed to attack the unions and slash social services, and the workers rose to defend themselves. There was no middle ground.

The series of mass rallies culminating in the Empire Stadium rally was evidence that the trade union leaders were at the head of a genuine mass movement that had a life of its own. But they were unfamiliar with this type of movement and entirely unprepared to lead it.

Increasingly concerned that things were getting out of hand, the trade union leaders shifted gears to tactics they were familiar with. They launched a petition to demonstrate to the government how unpopular their budget was. In addition they embarked on a “consciousness-raising drive” of educational workshops to explain why the budget was bad.

But this shift was confusing to most workers. The anger against the budget was already widespread and no explanation was needed. The workers understood that they were under attack and wanted to fight back. The momentum was carrying things forward seemingly all on its own. In this situation, the new phase represented a huge de-escalation.

The workers were doing something that B.C. hadn’t seen in a very long time and needed different tactics and ideas to lead them forward. Frustrated with this de-escalation, a layer of activists tried to break through this inertia imposed by the leadership.

The most notable action was a demonstration organized outside Human Resources Minister Grace McCarthy’s home on Aug. 27. The government and media used this to demonize Operation Solidarity, claiming the demonstration “violated the sanctity of the home”. This was the height of irony as they had abolished the Rentalman office and rent controls. How do the workers who get laid off and evicted or foreclosed on feel about the sanctity of the home? Government ministers simply wanted to be able to enjoy an undisturbed, comfortable life at the end of their hard day at work ruining the lives of the vulnerable.

The leaders of Operation Solidarity distanced themselves from anything appearing too radical. On a panel held on BCTV on Sept. 7, Kube, Munro, and Andstein distanced themselves from the protesters and claimed that they “were not a part of Operation Solidarity.”

Phase 3: The movement for the general strike

As the leaders were trying to prove how reasonable they were, many rank-and-file workers were drawing revolutionary conclusions. On that same BCTV panel, one worker called in and had the following exchange with the host, capturing the growing mood:

Caller: “I am a member of the international boilermakers here and I am an unemployed member right now and I think this sort of legislation is just ridiculous. I spent four or five months last year out of work in Alberta working in a few non-union places and it was the most disgusting I have ever seen in my life. The way they are going about this legislation now, it’s not going to help things out—not at all.”

Host: “So you’re with my panel this morning?”

Caller: “Yes.”

Host: “You are solid with Solidarity?”

Caller: “Yes. I’d even go for a general strike and even if it takes more than that.”

Host: “You can’t have more than a general strike.”

Caller: “Well, you could…”

The workers of B.C. could see that the old avenues were shut in their faces and were drawing the conclusion that things needed to escalate. But Art Kube and the other leaders found themselves reluctantly at the head of a movement that was moving in a direction they did not wish to go. The labour leaders increasingly resembled a captain of a ship, being tossed around by forces beyond their control.

The best example of this occurred when the Socreds announced that they would hold their convention on Oct. 15 in downtown Vancouver. The labour leaders were still harbouring illusions that if they just showed how reasonable they were, Bill Bennett would let them back to the bargaining table.

The leaders initially thought that protesting the Socred convention was a bad idea and argued that it would “distract from the petition” and “unleash the wrath of the workers”. But workers understood that this was the next logical step. It made no sense to do anything else. As the mood was overwhelmingly in favour of holding a rally, the labour leaders acquiesced, although not without reservations. Kube captured the feelings of the bureaucracy perfectly when he said: “Feelings are starting to run so high among the rank-and-file that [I am] personally hoping that the planned Oct.15 Solidarity march doesn’t get too large.”

Again, the leaders were being swept along by a great historical force. The working class was moving and it showed no signs of slowing down.

On Oct. 15, 70,000 people marched on the Socred convention. Socred MLAs tried to argue with the protestors only to be shouted down by a chorus of angry workers. To the delegates inside, their speeches had the backing track of tens of thousands chanting: “Socreds out!”

Still, the Socreds refused to take the movement seriously. Numerous Socred MLAs were quoted in the news referring to the protest as “funny” and the workers as “whiners, losers, and communists.”

This day led to a decisive change in the mood of the working class of B.C. They had tried everything, even a massive protest at the governing party’s convention, and still not gotten what they wanted. In the minds of the working class, the next logical step for the movement was becoming clear: a general strike.

Evelyn Farrelly, a hospital worker, gave a speech at the rally making the case for a general strike, stating, “It’s the only thing we have left.” The working class understood what needed to happen and the words “general strike” spread like wildfire into the halls of every workplace in the province. Postal worker Saria Andrew described the mood this way: “In my community and my union, almost everyone was preparing for an extended general strike and a community takeover.”

A revolutionary mood was developing within the working class of B.C. If the powers that be were not going to meet their demands, they were just going to have to take power from them.

A general strike is a concrete step towards revolution. It poses the question of power: Who really runs society? Who really makes the economy function? It poses a direct challenge to the capitalist state by revealing that the working class as a class has the power to run society without the ruling class at all.

On Oct. 18 and 19, the regional Gulf Island Solidarity Coalition and the Lower Mainland Solidarity Coalition as well as the Vancouver and New Westminster labour councils endorsed the call for a general strike.

On Oct. 22-23 a delegated solidarity conference discussed resolutions from Prince George, Prince Rupert, and Port Alberni delegates, calling for “a general strike until the entire legislative package is withdrawn.” According to Renate Shearer, fired human rights commissioner and coalition co-chair: “No question, people came to that meeting to plan for the general strike.”

Coming out of these discussions, the following plan of escalating strikes was developed:

Nov. 1: BCGEU workers

Nov. 8: 50,000 teachers and support staff

Nov. 10: Employees of Crown corporations

Nov. 14: Municipal workers and bus drivers

Nov. 18: Hospital and health employees

At the same time, private-sector unions representing 200,000 workers pledged themselves to take action.

On Nov. 1, the BCGEU began and their pickets were rock solid. Everything now depended on the teachers who were set to strike on Nov. 8.

The government was banking on the teachers strike falling flat. Teachers at this time were fairly petty bourgeois compared to the wider working class and had next to no tradition of striking. Indicative of this, ever since the 1950s, the BC Teachers’ Federation had voted to keep itself separate from organized labour. To top it all off, inside the teachers union there was an organization called Teachers Against Communist Tactics (TACT), which was trying with all of its might to sabotage strike plans. If the teachers supported the strike, this would be bringing one of the most conservative layers of the working class of the province on the road to revolution. To dissuade the teachers from striking, the government threatened to take away the teaching licenses of any teacher who went on a so-called “illegal strike.”

To the shock and dismay of the government, the teachers’ picket lines were solid and 90 per cent of all schools were shut down.

Tom Wayman, a teacher at Kwantlen College, captured the mood: “Our group met … every single day and debated whether to stay out or not. There were always people that stood up and said, ‘This is illegal, we shouldn’t do this, this is anarchy’… And every day there would be a resounding vote to continue.” Capturing the significance of this moment, he continued, “Everything was trembling on the edge of just a major transformation.”

Caught between the two classes in conflict sat the leadership of Operation Solidarity. Men who had for decades spent their time at the bargaining table were now being ground down between two great forces.

Kube, who had been at the head of Operation Solidarity since the beginning, went on live TV on Nov. 8 and broke down crying, stating: “I’ve always tried to play the role of peacemaker… and now it’s come to this!” These were the words of a man trapped between two armies engaged in class warfare—a man accustomed to class collaboration and legal negotiation, being carried forward onto the field of battle, kicking and screaming.

As the workers were developing in a revolutionary direction, the bourgeoisie started to comprehend what they were actually up against.

They had been banking on the teachers folding. They had been banking on organizations like TACT, succeeding in undermining the movement towards the general strike. But with 50,000 teachers on strike, things were barreling towards a general strike.

Even an RCMP memo at the time commented, “Following the first day of strike by the BC teachers, escalation of labour unrest seems inevitable.”

The next section of workers set to strike were the Crown corporation workers on Nov. 10. In particular, the ferry workers played a vital role in the B.C. economy and with these workers set to walk off the job, the Socreds started to panic. This was not “funny” anymore. Shutting down the ferries threatened to paralyze the economy, costing millions in profits.

This demonstrated the power of the working class. Not a wheel turns, not a lightbulb shines, not a ferry moves without the kind permission of the working class. And the workers had had enough.

The sellout

At this point, the question of leadership was absolutely decisive. Leading a mass movement like Operation Solidarity is not unlike leading an army into battle. The army of the working class was on the advance, against an enemy which had presented itself as sturdy, strong and unwavering. Now that the facade was starting to fall, the government began making overtures to the unions, opening doors they had slammed in their faces months ago.

An army faced with a wavering enemy on the battlefield would press their advantage to carry the day. Good leaders would explain to their soldiers that this demonstrated that the enemy was weak and they should press forward. But we have to remind ourselves who was at the head of this army of workers.

Unfortunately it was people like Art Kube, who at the moment of truth was crying, begging for class peace. Following this incident, Kube was given a leave of absence and was replaced by Mike Kramer, a career bureaucrat who played zero role in the mobilizations. The stage was set for one of the biggest sellouts in Canadian labour history.

On Nov. 10, on the eve of the Crown corporation workers going on strike, the leaders postponed the strike. But had the workers won? Had the Socreds withdrawn the restraint program? No, nothing so fantastic had occurred. Sharing a common fear of the masses, the government and the union leaders began secret negotiations to find a way to put the cat back in the bag.

On Nov. 13, Jack Munro of the IWA flew to Bill Bennett’s house in Kelowna. We can only imagine what transpired behind those closed doors. But when the two emerged a few hours later, they announced that an agreement had been reached. This famous deal became known as the “Kelowna Accord.” The flippant way these two men ended the most significant mass movement in the history of British Columbia was shown by the fact that there was nothing in writing. It was a simple verbal agreement and a handshake.

The unions called off the strikes and in return, the government promised to give way on the bills directly affecting the unions. Bill 2 was withdrawn and unions would be permitted to negotiate exemptions from Bill 3.

But all of the other bills would remain in place. The union leaders claimed that the government made a concession by allowing advisory committees for the other bills. But in the words of Bennett, they were given “nothing more than what was always offered; an opportunity to consult.”

Here the narrow business-union outlook of the trade union leaders was on full display. Instead of fighting for the interests of the class as a whole, they accepted a couple of minor concessions affecting exclusively their members and sold everyone else out.

In doing so, an opportunity of a lifetime was passed up. The blanketed nature of Bennett’s attacks created the perfect opportunity to unite the entire working class. This was a golden opportunity to demonstrate that the trade unions were not only fighting for their members, but the interests of the working class as a whole. Ironically, their business-union mentality and the sellout of Solidarity ended up weakening the unions themselves in the long run by proving in action that they did not care about anyone else.

The trade union leaders were not accustomed to a generalized struggle but were stuck in the legal structure of collective bargaining. As Kube stated: “I always took the position that you can’t negotiate these issues. That’s what got us into trouble [with the Solidarity Coalition.]” The fact that Kube, Munro, and co. were leading a movement called “Operation Solidarity” was therefore the height of irony.

But it’s not as though the unions got a stellar deal either. While BCGEU negotiator Cliff Andstein described this as a “no-concessions agreement,” the BCGEU was given wage increases of zero per cent for the first year, three per cent for the second year, and one per cent for the final year of the contract. Considering inflation was in double digits, this was an incredibly bad deal which ensured the further impoverishment of public-sector workers. Government negotiator Norman Spector said that they had “achieved a settlement that would allow the government to proceed with its announced target of reducing its workforce by 25 per cent.”

The government was free to lay off the 1,600 workers—and in fact, this was not something the leaders ever really disagreed with. In the words of Jack Munro: “I don’t think that anyone has said that they are opposed to or do not understand that there has to be some restraint.” Or we could take the words of the president of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association who, at the Empire Stadium rally, said: “They say they have a mandate, but if I can use my most colourful language, a mandate for circumcision is not a mandate for castration.” This shows the problem with the reformist outlook of the leaders. Because they accepted capitalism, they were forced to accept what capitalism could offer, which was counter-reforms.

This was a sellout of epic proportions, and to put the cherry on top, the labour leaders did not allow a vote on either the “Kelowna Accord” or the strike being called off.

At the BCGEU headquarters, the labour bureaucracy uncorked champagne bottles and celebrated the end of a stressful four and a half months. But the reality struck the rest of the working class hard. Patsy George, a fired public sector worker, stated: “[W]e were all in tears. It was a horrible betrayal.”

John Shields, a BCGEU member who relayed the terms of the accord to various sections of Solidarity, summed it up in this way: “It was whatever black day of the week it was. It was a day of mourning for me, certainly, and for the other public sector unions who had felt they had been betrayed.”

In the place of the hundreds of thousands of workers protesting, striking, picketing and demanding change, there were candlelight vigils. It was as if someone had died—and in a sense, something had died. The revolution had been aborted.

The crisis of leadership

It is easy to decry the leadership, the specific characters involved in this fiasco. Art Kube was a coward. Jack Munro was a traitor. There is no debating that. In fact, Munro, in his autobiography Union Jack, boasted about how he sold out the movement in the very first chapter, titled “Derailing the Solidarity Express.”

But a real Marxist analysis understands these figures not in a vacuum, but as a personification of a historical process. Ultimately, this is more important to understand than their individual traits, isolated from the historical process. This helps us to understand how the workers ended up with such bad leaders.

At first glance, it may seem incomprehensible that the leadership was so out of touch with the rank and file, but in actuality, this situation followed a logic all too common with trade unions under capitalism. The organizations of the working class (in particular their leadership) are not immune from the pressures of capitalist society. This was especially the case in a country like Canada during the postwar period.

During this period, a “social contract” between capital and organized labour was established through a system of collective bargaining. This gave legal status to the unions which allowed a larger layer of the working class to be organised.

However, as a consequence, the unions grew closer and closer to state power. As Leon Trotsky explained in Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay: “There is one common feature in the development, or more correctly the degeneration, of modern trade union organizations in the entire world: it is their drawing closely to and growing together with the state power.”

To the trade union leaders, it appeared as though they were struggling for influence over the state, which they saw as a neutral body that could be wrested from the control of corporate interests. But the state is not a neutral body and, under capitalism, it exists to protect the interests of the capitalist system. While the trade union leaders thought that they were gradually winning control of the state, all that was happening was that they were fusing the unions with state power, disarming them in the face of future attacks.

This process had an acute effect on the leadership of the labour movement. The tops of the unions had degenerated and instead of defending the interests of the workers, were more concerned with maintaining stability for the capitalist system. Trotsky explained in The Class, the Party and the Leadership: “Having once arisen, the leadership invariably arises above its class and thereby becomes predisposed to the pressure and influence of other classes.”

In an interview after the events of 1983, Kube, then president of the BCFED, in rather unprecedented honesty for someone in his position explained how the leadership had become divorced from the rank-and-file:

I find it very strange that although I was raised by a single parent mother in poverty and worked [from the time I was 13], it wasn’t until the development of the Solidarity movement that I realized how far from my own background I had come. Then I realized that the leadership of the trade union movement enjoys middle-class incomes, lives in middle class houses in middle class neighbourhoods. And then we started to think this way.

Therefore, the leadership had been conditioned by their experience of the preceding decades, where reforms were won through the parliament and collective bargaining. They were unaccustomed to a struggle of this magnitude and in fact feared the masses. This is why, while the workers were moving in a revolutionary direction, instead of leading them, the leaders tried to de-escalate the movement and limit its scope.

The need for Marxist leadership

What Operation Solidarity demonstrates above all else is the need for revolutionary leadership. The leaders of the movement in 1983 were leading a movement they did not know how to lead. This was admitted by Kube who explained: “The thing happened overnight and it sort of felt like building a motor car on the run. You just didn’t have the tools, the skills to really take advantage, full advantage of a situation.”

Moments like this don’t happen every day. During normal times, the workers are held down in a million and one ways by capitalism. But 1983 in British Columbia was one of those rare moments where workers rise up—and when they do, they need a farsighted leadership that is prepared to lead the struggle to the end.

However, this was precisely what was lacking. And history has proven that this is not something that can simply spontaneously arise. As Trotsky explained, “even in cases where the old leadership has revealed its internal corruption, the class cannot improvise immediately a new leadership, especially if it has not inherited from the previous period strong revolutionary cadres.”

Above all else, the main lesson from the tragic events of 1983 is precisely that the main task of revolutionaries is to build a revolutionary party in preparation for revolutionary events.

The largest Marxist group in B.C. at the time was the Communist Party. The CP had a long history in the province and B.C. was considered a stronghold of the party. They had some sway in municipal politics and were influential in the Vancouver and District Labour Council. The party also had significant membership in the meat cutters, longshoremen, carpenters, joiners, and fishermens’ unions. For example, George Hewison, who chaired the Lower Mainland Budget Coalition, was the secretary treasurer of the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union and a leading member of the Communist Party.

But the Communist Party of the 1980s was a completely different animal to the party of the early days. Decades of Stalinist degeneration had completely transformed the party. The party had adapted to capitalism and while it was “communist” in words, in deeds they capitulated under pressure and watered down their ideas.

This manifested itself with their general strategy of not criticizing the leaders of the movement, no matter how bad their leadership was. This was all done in the name of the “unity” of the movement. Hewison explained that the party had “refined the knowledge of how to operate in the labour movement to a fair science over 63 years and more.” What this meant was that the Communist Party was there “to play a constructive role…keep unity…aiming it at the Socreds, not the [labour] bureaucrats”. He continued, “You can’t have unity with those people and denounce them at the same time.” When asked, “How much thought do you give to the price you pay for doing that?” Hewison replied, “You don’t. You don’t worry about the price.” But the price for this strategy was fatal.

While the RCMP thought that Operation Solidarity was a communist plot, this couldn’t be further from the truth. University of Victoria adjunct professor Reg Whitaker explained, “CPers who did enter trade unions never had the opportunity to turn revolutionary rhetoric into practice: they were too busy just being good unionists securing better wages for their members. Even a few unions that ended up being run by CP officials were not really distinguishable from those closer to the CCF/NDP.”

This led Michael Walker of the Fraser institute to say: “Commie, schnommie—what matters is the ideas people run with, not with what they call themselves.”

The fact was that the Communist Party was no threat to the labour bureaucracy and actually played a useful role for them as a left cover for their actions. As Kube explained: “The Communists were no real power in Solidarity, really the opposite. In these situations I would use them.”

The Communist Party presented a false dichotomy—either you have unity and therefore don’t criticize the bureaucrats, or you “denounce” them and can’t have unity. This implies that criticism of the leaders would be bad for the “unity” of the movement. This is false to the core.

The policy of genuine communists is to strive for united action of the class, and this means working in practice side by side with union leaders that we don’t agree with. However, we must reserve the right to explain that the people with whom we unite are making mistakes. While this may undermine the authority of reformist union leaders, we have to ask ourselves, what is most important? That the best ideas eventually win, or that we preserve a “unity” that is leading to defeat?

Our policy is to positively explain what is the way forward, support the union leaders insofar as they take any step forward, and criticize the mistakes of the leadership at every step.

Lenin, when talking about the role of the communists in 1917 in relation to the leaders, said exactly this: that they needed “to present a patient, systematic, and persistent explanation of the errors of their tactics, an explanation especially adapted to the practical needs of the masses.” This approach should have been taken from day one in B.C. by the Communist Party. They should have been warning about the lacklustre approach of the trade union leaders, especially when they entered into demobilization mode with the petition.

As Trotsky explained when discussing the betrayal of the 1926 British general strike: “Temporary agreements may be made with the reformists whenever they take a step forward. But to maintain a bloc with them when, frightened by the development of a movement, they commit treason, is equivalent to criminal toleration of traitors and a veiling of betrayal.”

This is exactly how things ended for the Communist Party. When the sellout was announced, the Communist Party paper in their Nov. 16 issue called the sellout a “limited victory.” This amounted to covering up one of the greatest betrayals in Canadian labour history.

Communists today cannot repeat this mistake. We must organize ourselves as a separate tendency and put forward the ideas and methods needed to win. While we should not descend to shrill denunciations which teach no one anything, we cannot simply content ourselves with building the movement without any comment or critique on how the movement is being led.

In 1983, it was entirely possible that in these conditions, with the dastardly actions of the bureaucracy so evident, a small group of Marxists pursuing the correct policy could have grown very quickly, becoming a rallying point for the disaffected. As Trotsky explained, “during a revolution, i.e., when events move swiftly, a weak party can quickly grow into a mighty one provided it lucidly understands the course of the revolution and possesses staunch cadres that do not become intoxicated with phrases and are not terrorized by persecution.”

The Communist Party in B.C. may not have been able to change the ultimate course of events of the fall of 1983. However, with a genuine Leninist policy, a Marxist organization of that size could have come out being massively strengthened—having helped a wide layer of workers to learn from the events that had just transpired. Strengthening and growing the revolutionary wing of the movement by truthfully explaining the nature of the defeats along the way would have preserved the possibility of victory down the road. This could have allowed them to come out as a significant force, prepared to lead future struggles with the Mulroney government around the corner.

Unfortunately, the party did not come out of these events strengthened; precisely the opposite. As Kube explained: “in that situation, the left, and I mean more left than left, took a beating too, because today look at the left. Just about nonexistent. You know. That’s sad. I say sad because, you know, if you look at the labour movement and you look at their organizations, it is just about all lost. […] right now you go into a Fed convention, I don’t think that there are more than about three or four people who really represent the CP.”

This was the sorry result of Operation Solidarity. Not only was the movement defeated, but due to the nature of the defeat and the behaviour of the Communist Party, the labour movement and the left were massively weakened.

The nature of Operation Solidarity

But the betrayal of Operation Solidarity can never overshadow the incredible events that took place in the summer and fall of 1983. Operation Solidarity was a beacon for workers across the country. For 130 days, all eyes were on the province. Diane Wood, a public sector worker fired without cause under Bill 3, put it well: “Other unions were watching, other federations of labour were watching. If they could pull this off in B.C., it would move across the country very quickly and we would see a change like we had never seen before.”

But another class was also watching. Provincial and federal politicians and their capitalist backers were waiting to see how this would pan out. In the words of Frank Miller, the Liberal treasurer of Ontario: “I am watching what is happening with extreme trepidation. If Bill Bennett succeeds I think that every government will do the same thing in their own way.”

Just like Reagan’s fight against the air traffic controllers in the U.S. or Thatcher’s battle with the coal miners in the U.K., Canadian capitalists wanted to make an example of what was regarded as one of the strongest union strongholds in Canada. Crushing organized labour in B.C. would mean an all-out assault on the entire working class in Canada. And just like the defeat of the air traffic controllers and the coal miners, the defeat of Operation Solidarity was just the beginning of a period of decline for the unions in Canada.

But was this all inevitable?

It was clear that Bennett would not have backed down without escalated labour action. However, we are told by labour leaders, capitalist historians, and politicians of all stripes that a general strike would have been an unmitigated disaster.

Even many so-called Marxian scholars contend that, for this or that reason, Operation Solidarity could never develop into a revolution—a general strike, maybe, but never a revolution.

For example, Bryan Palmer, a Marxist academic who wrote the best Marxist account of the events, describes the movement as “a purely defensive struggle in a non-revolutionary situation.”

It seems like even when the working class is at the precipice of revolution, at the 11th hour ready to force their way onto the scene of history, there will still be people denying reality.

But in the words of the great German revolutionary Rosa Luxembourg: “Before a revolution happens, it is perceived as impossible; after it happens, it is seen as having been inevitable.”

It’s easy to look back at a defeat and declare that revolution was not on the agenda. But the fact of the matter is that B.C. was on the verge of a revolution. The working class was on the move and was entirely capable of overthrowing the government and taking power into their hands. This would have been a boon to the movement across Canada and could have completely transformed the situation in the labour movement.

The outcome of events is not determined in advance. While Marxism teaches that there are general laws of historical development, this does not eliminate the need for human action. As Marx explained, “History does nothing, it ‘possesses no immense wealth’, it ‘wages no battles’. It is man, real, living man who does all that, who possesses and fights; ‘history’ is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.”

But some so-called Marxists have even tried to smuggle in a fatalist argument in Marxist clothing. They argue that because there was no revolutionary leadership, the workers could not win at all.

For example, Leo Panitch and Donald Swartz, two Marxist academics, argue: “Few would seriously suggest that unions could win such a confrontation alone without a party which provided a political alternative to the existing government.”

Jack Scott, a Marxist author who participated in the events, argued against the general strike, saying: “Bennett would have carried the people. ‘Who is going to rule the country? Us or the unions?’ Let’s not kid ourselves about what would have happened.”

Even George Hewison, a key Communist Party leader at the time, justifies this argument explaining: “Well, that was the problem, you see. I mean, yeah, we could bring down the government, but we didn’t have a government waiting.”

But this argument falls flat with a cursory look at the history of the class struggle internationally and in Canada. Just 11 years prior to Operation Solidarity, the Québécois workers in 1972 embarked on an insurrectionary general strike without a revolutionary party of their own. While they were ultimately unable to overthrow capitalism without a revolutionary party, they did succeed in making some significant gains. And today, the Quebec labour movement has the highest unionization rate in the country as the workers maintained a fighting tradition. The workers in Quebec, although power had slipped through their fingers, were not utterly demoralized. Following this strike, the revolutionary left in Quebec was in the ascent. This was similar to the way things developed after the defeat of the Winnipeg general strike of 1919, in which many drew the conclusion that they needed to build a Communist Party on the lines of the Bolsheviks of 1917.

Ultimately, without a revolutionary leadership, workers in B.C. would not have been able to overthrow capitalism. This is true. But to therefore draw the conclusion that they should not have done whatever it took to fight back against the attacks of the government, and that they would inevitably lose, is just fatalism.

While it is impossible to know exactly how things would have played out if the general strike had taken place, what we do know is that what transpired was the absolute worst way to go down to defeat. Speaking of a similar situation with the betrayal of the 1926 British general strike, Trotsky explained: “No revolutionist who weighs his words would contend that a victory would have been guaranteed by proceeding along this line. But a victory was possible only along this road. A defeat on this road was a defeat on a road which could later lead to victory.”

A defeat without a fight is the most demoralizing kind of defeat. But when workers go down in defeat while putting up a fight, they learn great lessons and build traditions that carry forward into the future. For example, while workers were defeated in the Winnipeg general strike of 1919, this event is still celebrated. Additionally, the result of 1919 was that many activists went on to form the Communist Party and the trade union movement was ascendant. Similarly, in 1905 in Russia, the general strike was ultimately defeated by the forces of the tsar. However, this movement served, in Lenin’s words, as “the dress rehearsal for [the revolution] of 1917”.

Of course, orderly retreats are entirely necessary when faced with an unfavourable situation. A healthy, farsighted Marxist leadership knows not simply how to advance, but also how to retreat and prepare for a more favourable moment. However, this was not an unfavourable situation at all—precisely the opposite! The moment of the betrayal was when the movement was at its height, going from strength to strength, and the government was retreating.

Countless testimonials from workers who participated in the events of 1983 attest to the simple fact that the working class of B.C. had entered the political arena. A qualitative shift was taking place: a revolution was being born.

Prepare for a new 1983

With the leaders that B.C. workers had, it is actually astounding that the movement in 1983 got as far as it did. To this, we owe gratitude to the hundreds of thousands of proletarians who remain unknown to history. But as this example demonstrates, while the masses may be able to pressure their leaders and temporarily push them forward, they are unable to spontaneously throw up a new leadership—one capable of leading the struggle to its logical conclusion. This central lesson stands out starkly.

After the events of 1983, Kube stated, “I think that it’s doubtful that the labour movement could mobilize to the same extent as we did then.” But Kube’s pessimism only reflects his lack of faith in the working class. Today, the crisis of the capitalist system is creating revolutions in country after country, with no need from weak leaders like Kube. From Sri Lanka to Kenya to Bangladesh to Peru, the masses are rising up. And we can already see the outlines of a revolution developing in Canada. All of the factors that led to the uprising in 1983 in B.C. are present today and the capitalists are hopeless to improve the situation.

The most important task for revolutionaries today is to build in preparation for a new 1983. Countless movements like Operation Solidarity have come and gone with sellouts and many moaning on the sidelines. But if we understand that capitalism is a system that has crisis hardwired into it, and we understand, as Rosa Luxemburg said, that our choice is to fight for socialism or descend into barbarism, we must build a strong Marxist party like Lenin did with the Bolsheviks in order to provide leadership to the masses in struggle.

This is why we launched the Revolutionary Communist Party in May this year. Our first task is to learn the lessons of the past. Only in this way will we be able to lead the workers to victory in the coming storm of the class struggle.