A recent poll by the Toronto Star found that nearly 60 per cent of Canadian workers agreed with the statement “I’d be happier if I didn’t have to work at all”.

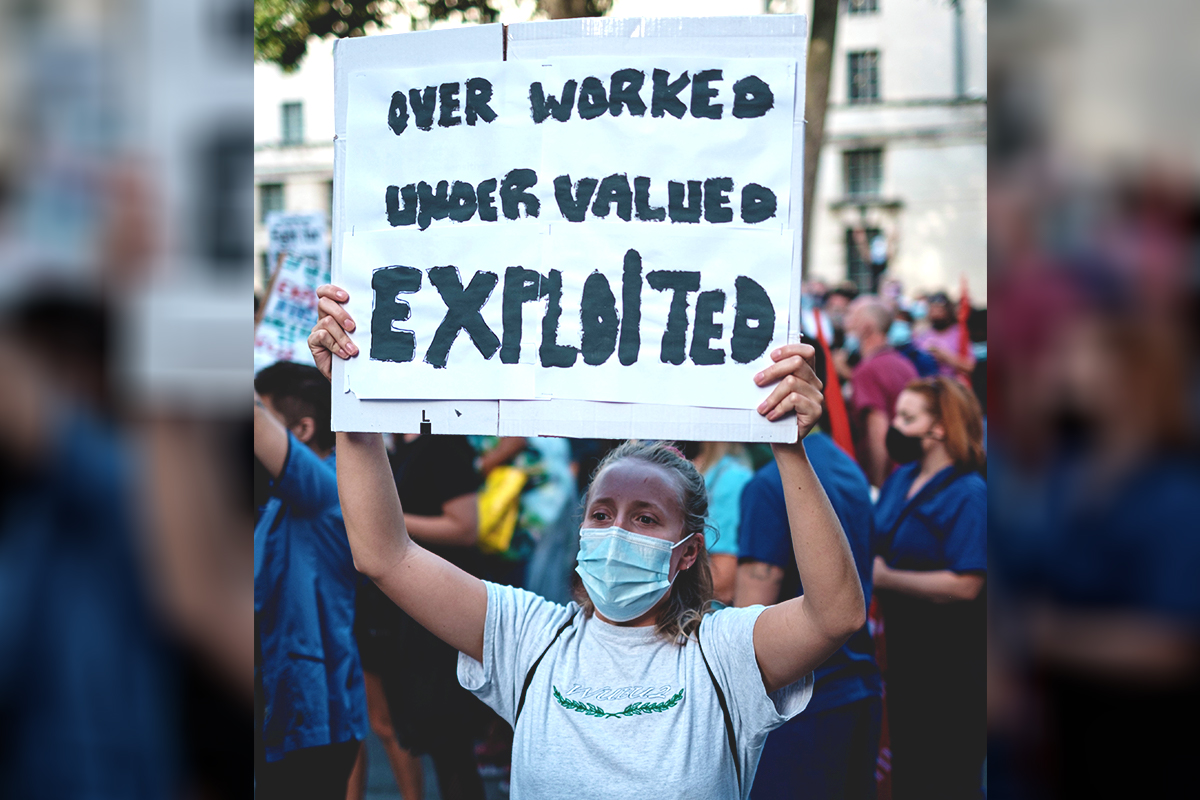

In fact, over the past few years, we’ve seen a growing movement against work—or at least against the current conditions of work under capitalism.

Antiwork

This past fall, a TikTok of a young woman tearfully breaking down over the drudgery of her first full-time job went viral.

The young woman described being forced to spend about three extra hours commuting every day, for the same pay. This, in addition to unpaid time spent answering work emails and other off-hours work, makes the working day extend far beyond the legal limit of eight hours. Despite remote work being possible for many jobs, bosses keep trying to force workers to come back to the office, adding more and more hours to the working day.

Many on the right mocked her, saying it was typical of this new generation who just don’t want to work. But who would want to work longer and longer hours for less and less pay?

In the last few years, many workers have asked themselves the same question.

@brielleybelly123 im also getting sick leave me alone im emotional ok i feel 12 and im scared of not having time to live

This trend has become known online as the “anti-work movement”. These people aren’t against the idea of work as such, they just don’t want to waste their lives working for capitalist profit. The top post on r/antiwork has the headline “Quit my job last night, it was nice to be home to make the kids breakfast and take them to school today! Off to hunt for a new opportunity, wish me luck :)”. Clearly, this worker wants to have a job; they’re trying to get a new one in the title of the post. At the same time, they want to have a life outside work as well.

One worker put it this way; “No one actually wants to work. We live on the most beautiful planet in the solar system, with waterfalls, aurora borealis, and the stars in the sky. Why would anyone actually want to work for five days a week for pieces of paper”.

Another worker is quoted as saying “I love my job, but if I didn’t have to do it, I wouldn’t. Or at the very least, I’d reduce how much I work.” Even for people who are working jobs they enjoy, long hours and long commutes can take away any enjoyment.

Far from a sign that workers are getting lazier, the rise of anti-work sentiment shows that workers are tired of putting up with terrible conditions for long hours, wasting their lives at a job that still leaves them too poor to survive.

Workers are entirely right to be frustrated and angry with the exploitation they face.

Working more for less

In the past there was some appearance of work being worthwhile. If we were good employees, we could advance in our jobs, make more money, have a higher quality of life, and eventually comfortably retire. That isn’t the case anymore. It is now obvious to workers that their labour is not going towards improving their own lives, but just contributing to the profits of the capitalists (again, as demonstrated by trending TikTok videos).

This shift in mindset is notable enough for Business Insider to report on, quoting Panera Bread CEO Ron Saich, saying, “No employee ever wakes up and says, ‘I’m so excited. I made another penny a share today for Panera’s shareholders. Nobody cares. You don’t care whether your CEO comes or goes.” We would simply add, “no duh”.

In recent years we’ve seen rampant inflation, increasingly unstable job security, and a global pandemic that exposed the protections workers have won, such as sick days, as a complete sham. One worker states that their job “doesn’t pay enough to buy anything for fun nowadays. Most of my money goes to rent and food … over-the-top prices for the same things three years ago!”.

As we said at the time, workers have been made to pay for a crisis of the boss’ making. Inflation, followed by rising interest rates, has made it so that two thirds of Canadians 18-34 worry about affording rent in the next two months. At the same time, corporate profit is higher than it’s ever been.

It’s no wonder workers don’t see the benefit in working long hours to make their bosses rich while they starve.

In addition to this, many workers are having to take on a second job. Many employers don’t offer full time hours (in order to avoid paying benefits), meaning workers have to stitch together multiple jobs in order to afford to live, often working more than 40 hours and not receiving the benefits they’d normally be entitled to.

This has been reflected in the rise of gig work. More than a quarter of Canadian workers have been forced to take on these jobs. Due to their status as independent contractors, which companies such as Uber lobbied the government for, these jobs are subject to essentially zero regulation. This means that workers aren’t even guaranteed the pitiful minimum wage other jobs are. This, along with the inherently unstable amount of work, means that workers have no way of knowing how much money they’ll make.

For workers who complain, they are threatened with their job being automated. There’s been a lot of talk in the bourgeois press about how AI is going to revolutionise work by automating millions of jobs. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon has even predicted that this could lead to a 3.5 day work week. This seems wonderful in theory, but under capitalism this would be catastrophic. There would be mass unemployment, with millions of people having their jobs automated out of existence, and with no corresponding growth in the labour market.

Even if, as Dimon seems to be suggesting, this is achieved by maintaining the number of jobs in total, but reducing the number of hours everyone works, this also causes massive problems. A 30 per cent reduction in the working week is only useful if it isn’t matched with a 30 per cent reduction in pay. The latter would simply push workers into the same precarity of the gig economy described above.

The charm of work

Automation does not have to be a nightmare for workers. On the contrary, automation would free humanity from the drudgery of manual data entry, bookkeeping, and other mindless tasks. But under capitalism, it just means further degradation of work itself.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels state that “the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and, consequently, all charm for the workman”. This is clearly the case with many jobs today.

In the Toronto Star poll, a miner states that “It’s great to do nothing”, while a ballet dancer says “I feel like I’d have something missing in my life” without their job. The Star presents this as just two different perspectives on working life, with no further analysis. Some people like work, and some don’t.

This ignores the major differences between mining and ballet dancing. The former is hard physical labour, deep underground, that’s often very dangerous. The latter is artistry conveyed through the human form.

Many more workers are quoted as saying that their work provides meaning in their lives, that they take pride in their work, and that their work provides much needed opportunities for human interaction.

We see the contradiction of labour under capitalism. Labour is how we interact with the world around us, and yet under capitalism the human capacity for labour is just a tool to deepen the pockets of the bourgeois.

The low pay, the long hours, the lack of security. These things are not qualities of labour universally, separate from the particular system in which the labour is conducted. These are all features of the particular form that labour takes under capitalism.

As Marx wrote in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844,

“What, then, constitutes the alienation of labour?

“First, the fact that labour is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home. His labour is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labour. It is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labour is shunned like the plague.

“External labour, labour in which man alienates himself, is a labour of self-sacrifice, of mortification. Lastly, the external character of labour for the worker appears in the fact that it is not his own, but someone else’s, that it does not belong to him, that in it he belongs, not to himself, but to another. Just as in religion the spontaneous activity of the human imagination, of the human brain and the human heart, operates on the individual independently of him—that is, operates as an alien, divine or diabolical activity—so is the worker’s activity not his spontaneous activity. It belongs to another; it is the loss of his self.”

What we see today is exactly this alienation. The promise of communism is that instead of labouring to enrich others, workers will labour to build a society that they play a democratic role in shaping. Instead of checking their individuality at the door, workers will run their workplaces, and their ideas and creativity can find expression through their work. Combined with reduced hours and the provision of “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”, work will no longer be a burden, but a source of fulfillment.

Under a communist system, work wouldn’t be an endless slog through meaningless paperwork, or a stressful minimum-wage service job. Trotsky asked “How many Aristotles are herding swine, and how many swineherds wear a crown on their heads?”. It is only through communist revolution that we can build a society that fully harnesses the potential of humanity.