This article is a translation of an article originally published on our French language website.

Bill 96, “An Act Respecting French, the Common and Official Language of Quebec,” was tabled by the CAQ last May, and has been under debate in parliament and in the news for months. It is essentially an update of Bill 101. While there is widespread opposition to this bill in the English-speaking community, all political parties and trade unions either agree with it, or think it does not go far enough.

The left-wing party Québec solidaire (QS) regards Bill 96 as “a good step forward” in supporting the French language. Quebec’s major union federations have endorsed it, with the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ) claiming “the bill is a breath of fresh air”. The Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN) adds that “a majority of the proposals made are in line with [its] demands,” and, for its part, the Centrale des syndicats du Québec (CSQ) regards the bill as meeting its expectations.

Clearly when all the labour organizations and QS are more or less behind a right-wing reactionary government, something is wrong. Where does this strange, near-unanimity come from, and what should the socialist position be on this issue?

What is this all about?

If Bill 96 comes into force, Quebec will amend its part of the Canadian constitution to add the following statements: “the Quebecois form a nation” and “French is the only official language of Quebec. It is also the common language of the Quebec nation.”

Beyond the symbolic statements, Bill 96 will modify the enrolment quotas for English-language CEGEPs. Their full-time enrolment will not be allowed to exceed 17.5 per cent of the total CEGEP enrolment in Quebec, and the annual increase in places will be limited to 8.7 per cent of the total increase. In other words, if 10,000 new students are added at the beginning of the school year, 870 of them will be able to join the English-language network. Simon Jolin-Barrette, Minister responsible for the French language, explains: “We have specifically provided for college institutions to give priority to those who are entitled to it, i.e. English-speaking students who have completed their primary and secondary education in English”. This could result in more English-speaking immigrants being denied the opportunity to continue learning in their language.

Bill 96 also includes measures regarding the language in which public services will be provided. Notably, it states that “administrative bodies shall implement measures that will ensure communications exclusively in French with immigrant persons at the end of a six-month period.” It seems that now the six-month period will simply be a transitional clause for special situations. Otherwise, as Jolin-Barrette said, “In the case of of newcomers, the fundamental principle of this law is that from the second an immigrant lands in Quebec, everything that follows will happen exclusively in French.” This means that immigrants, who already have to go through a bureaucratic obstacle course worthy of the Twelve Labours of Hercules, will have to do so in a language they do not necessarily understand.

In an interview with Mathieu Bock-Côté last June, Professor Guillaume Rousseau, who has a positive view of Bill 96, explained that with this bill, “the state and public agencies will have to put an end to their practice of offering public services in English to almost everyone who requests them. Henceforth, public services will be provided in French, and access to public services in English will be limited to exceptional cases, not for all anglophones, anglicized allophones, and immigrants, for example, but only for members of the historic English-speaking community – as defined by the criteria for access to English-language schools – and immigrants who have been in the country for six months or less” (our emphasis).

It is truly shameful to see the unions and the left supporting a bill that aims to make life more difficult for non-French speaking immigrants. Québec solidaire’s parliamentary representatives have taken the cowardly position of simply abstaining on the motion stating that immigrants will be served only in French. Why? Does QS oppose this ridiculous rule, yes or no?

We recently saw what the consequences of the bill would be, and how it will be used by the CAQ. The government recently canceled the expansion project at Dawson College, an English-language college, on the pretext of wanting to allocate funds to French-language CEGEPs, even though the Ministry of Higher Education recognizes the shortage of space at the college. This is the twisted logic of the CAQ: cutting education under the guise of defending French. If the CAQ were truly interested in education, it would adequately fund all schools, without exception, rather than cutting funding to English schools to supposedly bail out French ones.

French in “free-fall”?

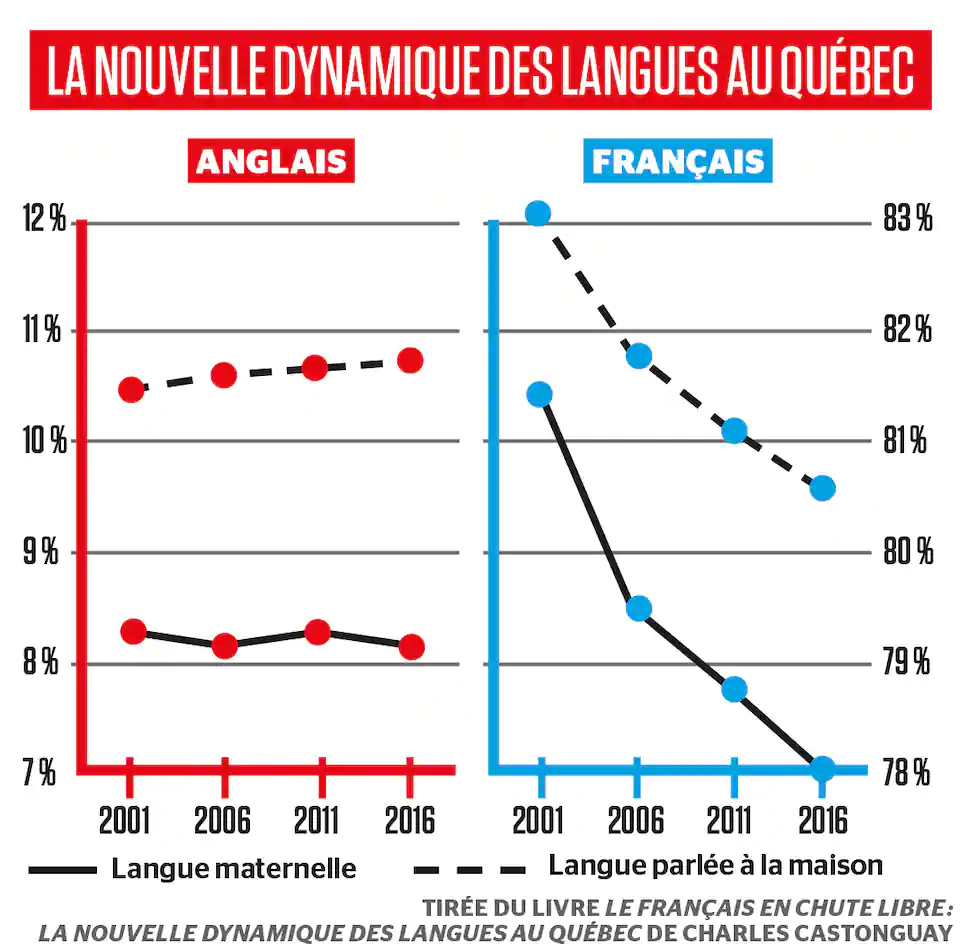

The government justified the urgency of ratifying Bill 96 on the basis of a so-called “free-fall of French.” François Legault, during the last election campaign in 2018, stated: “There is a risk, Quebec and French will always be vulnerable. It is the responsibility of the Premier of Quebec to protect the nation, to protect French in Quebec.” The mainstream media, including the Journal de Montréal, disseminated this alarmist message. Mathieu Bock-Côté, for example, said, “For this is the issue: not only is anglicization on the march, but it is accelerating.”

By playing this card, the CAQ is striking a nerve. The history of oppression of the Quebecois is still very vivid in the memory of those who lived through the 1960s and 1970s in particular. It was our class, the working class, that suffered. The Quebec working class was mercilessly exploited by Anglo-imperialism. In addition to economic exploitation, there was national oppression and humiliation: Quebec workers were too often forced to speak English in the workplace. Relics of the past, such as the case of Air Canada CEO Michael Rousseau, who recently boasted that he never had to speak French in Montreal and didn’t want to learn it, sometimes stir up hatred of oppression among Quebecers, showing that Anglo-chauvinism is still alive and well among the ruling class in Canada.

The hatred of this linguistic oppression has been passed on to subsequent generations and still exists in the Quebec population. Bill 101 is widely seen as having played a progressive role in this struggle against oppression.

But since the 1970s, most of the worst manifestations of the francophones’ oppression have faded. There is now a well-established “Quebec Inc.” that exploits us in French. This does not stop the identitarian nationalists from using the progressive sentiment of Quebecois people to fight against oppression to suit their own ends. Their mantra of the imminent decline of French is part of this trend. But whatever the identitarian nationalists may say, the facts tell a different story.

What are the facts? Ninety-four percent of Quebecers are able to conduct a conversation in French. The Office québécois de la langue française estimates that this number should remain fairly stable, at least until 2036. Statistics Canada admitted in 2017 that it had overestimated some of the figures on the decline of French and the growth of English.

The identitarian nationalists base their rhetoric on two indicators: the decline of French as the only language spoken at home, and its decline as a mother tongue. It is easy to see who they blame: immigrants. But what does it matter whether a household speaks Arabic, Urdu, French or Creole at home? As QS representative Ruba Ghazal explains:

“It is in French that I have grown up in Quebec, that I have become an adult, that I have studied up to a Master’s degree, and that I work. But at home, it has always been in Arabic, my mother tongue. I am not the exception, there are many Quebecers who speak another language at home while living outside in French. Why do some politicians, columnists and activists think that I am a problem for the protection of French in Quebec? Why do they consider people like me a bad statistic for the future of our common language?”

The identitarian nationalists completely ignore the fact that while French is declining as a mother tongue and as the only language spoken at home, the same trend is observable in Canada for English. Statistics Canada states that these trends will have “a limited effect on the relative demographic weight of official language groups in the country, both in Quebec and in the rest of Canada.”

In fact, the proportion of the population speaking French at home has increased from 87 per cent in 2011 to 87.1 per cent in 2016, although the proportion speaking only French has decreased slightly from 72.8 per cent in 2011 to 71.2 per cent in 2016. The same is true for English. English spoken at home increased slightly from 18.3 per cent in 2011 to 19.2 per cent in 2016, but the proportion speaking only English at home decreased from 6.2 per cent in 2011 to 6 per cent in 2016. Both languages decreased slightly as a home language: 79.7 per cent in 2011 to 79.1 per cent in 2016 for French, and 9.0 per cent in 2011 to 8.9 per cent in 2016 for English.

Additionally, 33 per cent of immigrants who arrived before 1981 reported speaking French most often at home in 2016. This figure rose to 41.5 per cent for immigrants who arrived between 2011 and 2016, while English drastically decreased for the same groups, from 30 per cent to 9.5 per cent.

The figures clearly show that we are far from a “free-fall” of French, and even less from an invasion of English speakers. Rather, these figures are explained, on the one hand, by the fact that more and more Quebecers are bilingual, and on the other hand, by the immigration of other language groups such as Arabic and Spanish speakers. The so-called “free-fall” of the French language seems to be a collective hysteria of the right-wing identity nationalists.

Unfortunately, this discourse is generally accepted by the left. Québec solidaire’s website states, “At a time when the decline of French is of great concern to the Quebec population, the person responsible for language for Québec solidaire, Ruba Ghazal, is asking Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette to take the bull by the horns and put in place a specific plan to redress the situation of French in Montreal.” By accepting the rhetoric of the CAQ and the identitarian nationalists, we are again letting them dictate the debate. They can then present themselves as defenders of francophone workers, and divide us on linguistic lines.

National unity

For the past four years, the CAQ has maintained its position at the top by claiming to be defending the nation, in the manner of Maurice Duplessis. Whether with Bill 21, the infamous religious symbols ban, or now with Bill 96, the objective is to create a national unity behind the party, to unite Quebec workers and their bosses against an external enemy, be it the immigrant, the Muslim or the Anglophone. Identitarian nationalism is and will be the CAQ’s weapon of choice to make us forget their horrible management of the pandemic.

In the midst of a pandemic, the government considers the protection of the French language to be its “top priority.” Making the protection of the French language its “top priority” while people are dying and the economy is on the brink of collapse: the audacity!

Famous Quebecois trade unionist Michel Chartrand once spoke these wise words:

“The nationalists will forgive the worst turpitudes of the PQ (Parti Quebecois). They are ready to forget that there is a huge difference between nationalism and true national liberation. That is why I have always been against those ‘nationalists’ who want to save the language while letting those who speak it die.”

Today, the same could be said of the CAQ. The virus may kill us, but at least it will kill us in French!

For a class based solution

As with any question, the starting point for Marxists is this: what helps strengthen the unity of the working class in its struggle against the bosses, their friends in government, and all forms of oppression, is progressive, and what divides or weakens it in this same struggle is reactionary.

How can absurd measures that will prevent non-French speaking immigrants from accessing public services in a language they understand strengthen the workers’ struggle and the fight against oppression? To the contrary, it can only alienate immigrants and help divide workers. In this context, Anglo-chauvinists can also hypocritically denounce these measures, and themselves pit Anglophone workers against Francophones.

The CAQ’s Bill 96 will simply give Legault more ammunition to present himself as the great defender of the Quebec nation, without even really promoting French language learning. In this context, the left and the labour movement should oppose Bill 96. It is truly incredible that making life difficult for English-speaking immigrants and preventing the expansion of a CEGEP, under the pretext that it is English, has not yet elicited a reaction from the Francophone left. The CAQ is once again playing Quebecers for fools on the backs of minorities.

The CAQ’s identitarian nationalists are able to cancel Dawson’s expansion without causing too much of a stir among francophone unions, using the argument that francophone CEGEPs are underfunded. But this raises a real problem. Schools in general are underfunded. The education system is adrift. The solution cannot be to underfund English-language schools!

Similarly, Ruba Ghazal of QS points to real problems for workers, such as the fact that “many French-speaking immigrants cannot find jobs because of their unilingualism” and that our level of English is tested when hired, even if it is not essential to the job. Conversely, it is difficult for a unilingual English-speaking immigrant to find a good job in Quebec, even in Montreal.

So what is the socialist solution to language in Quebec?

Rather than shoving French down the throats of immigrants with bureaucratic measures, which will only disgust them, we need to encourage and help people to learn and speak French by devoting all the necessary resources. In addition to investing massively in Quebec’s culture, we must fund French courses sufficiently, by granting decent allowances to immigrants taking French courses.

It is completely hypocritical for the nationalists in government to cry disaster over the status of French when they are not even prepared to spend money on it. French courses are a joke today. How can we expect immigrants to take French courses when full-time courses cost a ridiculous $200 per week, almost enough to pay the rent! Not to mention the long processing times, which cause many immigrants to simply give up and go back to work in English. Ironically, it was the “great nationalist” Lucien Bouchard who cut the funding for French courses for immigrants by closing the orientation and training centers for immigrants when he was Premier.

We also need massive funding for all schools: primary, secondary, CEGEPs, universities. We need a completely public and free education system. Since French is the language of the vast majority of the population, most schools will of course offer their courses in French. There is more than enough wealth for quality education in all languages.

We must put an end to all discrimination in hiring based on language. If a language, be it French or any other language, is needed for a job, courses must be offered to all workers who need them, paid for by the employer.

But all these measures are in direct contradiction with the capitalist system. From the point of view of the CAQ and the bosses, this is not the time for massive school funding and increased funding for culture and language learning. This is a time for belt-tightening. For the CAQ, school funding is a zero-sum game: either Dawson is funded or the francophone CEGEPs, but not both. Similarly, employers certainly don’t want to have to pay for language courses for their employees. We say: let’s nationalize the big companies under the control of the workers, let’s free up the immense resources that exist but are monopolized by a minority of rich people. With these resources, let’s fund all our schools, and offer courses in French and in all the languages needed by a given community.

Only a class program can cut through the CAQ’s attempt to rally the “nation” behind it. Only such a program can end the linguistic divisions and promote the unity of the entire working class in Quebec. In addition, such measures will do much more to promote French learning than the CAQ’s ridiculous, bureaucratic methods.

That being said, what is dying right now is not French. It is the victims of COVID-19, it is the essential workers, it is the poorest. The bosses sacrifice the lives of workers for the sake of profit during the pandemic. The government has left our education and health care systems on the brink of collapse. What we need most right now is not “national unity” with our French-speaking bosses, but unity of the workers and the oppressed against the bosses, who have enriched themselves at the expense of our lives during the pandemic, and against their representatives in the CAQ government.