The following article is featured in our new booklet, “Communism or Mutual Aid?” You can buy the booklet here.

In recent weeks, we have spoken to and received write-ins from thousands of workers and youth who urgently want to build the revolutionary party. There are no illusions among this layer that capitalism can be reformed into a functioning, just system. They are crystal clear on the need to overthrow capitalism with revolution, and they are burning with desire to act toward this goal. Time and time again, we hear the same sentiment: “I want to do something.”

With this sentiment, we couldn’t agree more. Capitalism is on the brink and the time to act is now. Even in a wealthy nation like Canada, only the ultra-rich are really doing ok. Minimum wage is not enough to cover the average rent in most cities, the prices of basic necessities like groceries have risen dramatically, and the oppression of marginalized groups has not abated. The list of crises goes on, but in short, capitalism is making millions of working class people feel that the walls are closing in. In this context, it’s only inevitable—and extremely positive—that so many new communists want to take action immediately.

With this desire to act has come an increased interest in mutual aid, which we have received many questions about in recent months. This is no surprise. Mutual aid promises concrete, “material” change in the here-and-now, which resonates with the urgent desire to act felt by so many communists today.

The most basic idea of mutual aid is that workers can help each other meet their needs by collectively sharing services, money, or other resources. There are varying interpretations of what mutual aid can achieve politically, but Dean Spade, author of the popular book Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis, outlines three functions of mutual aid which are accepted by many left activists. He argues that mutual aid can “build shared understanding about why people do not have what they need,” “mobilize people, expand solidarity, and build movements,” and states that “mutual aid projects are participatory, solving problems through collective action rather than waiting for saviours.”

It’s easy to see why so many are interested in helping others through mutual aid. There are millions of poor and working people who have been left to slip through the cracks by capitalism—forced to sleep on frozen sidewalks, trapped by poverty in abusive housing situations, unable to afford necessary medications, and so on. For many new communists, it only seems right that we should try to help those whom capitalism has crushed the hardest. This is a positive instinct, and the fact that it is felt by so many thoroughly disproves the anticommunist myth that human nature is inherently selfish. Rather, thousands of workers and youth urgently want to help those in need, and in many cases it is precisely this desire which draws them to revolutionary conclusions.

We fully agree with those communists who are interested in mutual aid that we must act urgently to end all the suffering caused by capitalism. For us, this is inarguable. But the question is: how?

We must take action, yes—but not haphazardly. Everything we do must be carefully evaluated with the end goal of communist revolution in mind. Only revolution can rip up the roots of poverty, exploitation, and oppression, so it is crucial that every tactic or strategy we take up serves that end goal. This means that we cannot accept the commonly-repeated refrains about mutual aid at face value. Improving the conditions of the working class, encouraging solidarity, and building movements are all very important goals—but is mutual aid really the way to achieve them?

Scooping water out of a sinking ship

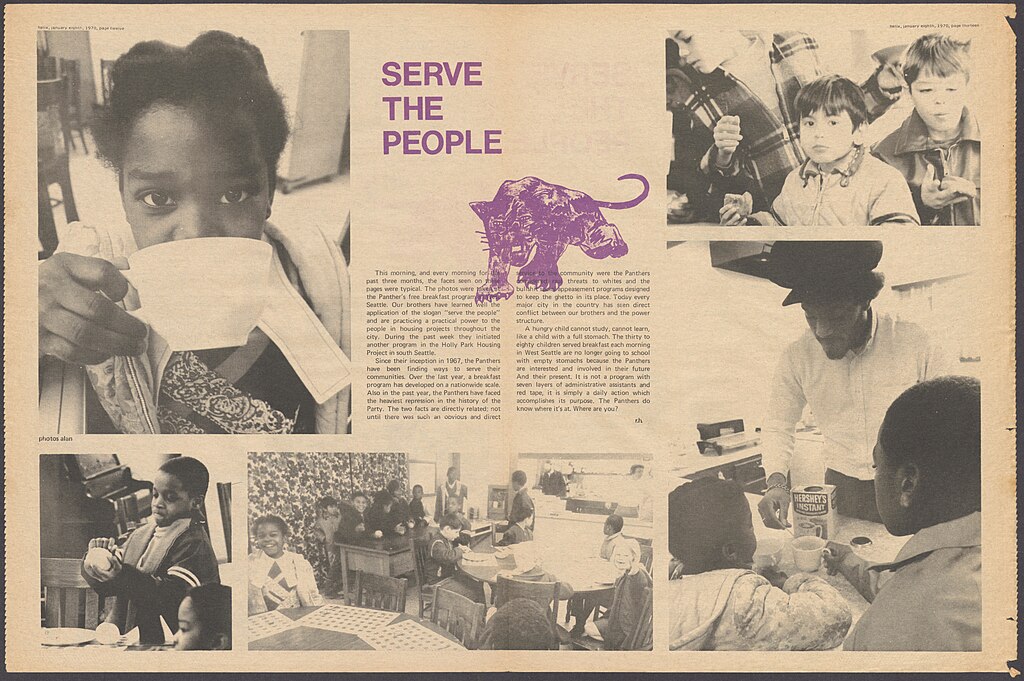

Many communists, recognizing the bleak conditions faced by workers, see mutual aid as a necessary way to improve workers’ conditions until the overthrow of capitalism. This idea of mutual aid as a way to secure short-term survival can be traced back to the Black Panther Party (BPP), whose work in the 60s is commonly cited as proof of the potential of mutual aid.

The BPP is best known for its “Breakfast for Children” program, which at its peak served 45 branches across the U.S. It was run in conjunction with various other “survival programs,” which organized everything from community land trusts to the provision of free shoes.

In 1969, the year the Breakfast for Children program was launched, reports showing the extent of hunger and malnutrition across the country sent shockwaves across the U.S. It was a moment of embarrassment for bourgeois politicians as headline after headline declared that over a million children were going hungry in the richest country in the world. It’s clear that there was a need for immediate relief. But to what extent did the survival programs provide that relief? Did they play a decisive role in helping the working class improve its conditions?

That first year, the Panthers’ breakfast programs fed 20,000 children in 23 cities. This forced the national School Lunch Program administrator to publicly admit that the Panthers fed more children than did the State of California. Over time, it’s estimated that 50,000 children were fed by the Panthers’ breakfast program.

Despite this, the BPP did not argue that these survival programs were revolutionary in and of themselves, but defended them as a necessary way to ensure “survival pending revolution.” Huey P. Newton, one of the original founders of the BPP, compared them to the “survival kit of a sailor stranded on a raft”:

“All these programs satisfy the deep needs of the community but they are not solutions to our problems. That is why we call them survival programs, meaning survival pending revolution. We say that the survival program of the Black Panther Party is like the survival kit of a sailor stranded on a raft. It helps him to sustain himself until he can get completely out of that situation. So the survival programs are not answers or solutions, but they will help us to organize the community around a true analysis and understanding of their situation.”

Moreover, while these numbers are impressive, the reality is that they fell far short of solving the problem. The results were a drop in the bucket compared to what the welfare programs soon implemented by the state would do, and to the scope of child hunger in general. In 1970, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Food Service’s breakfast program fed 500,000 children—10 times the number of children fed by the Panthers at their height. Then, in 1973, Congress passed a dramatic increase in funding for the national School Lunch program, and two years later authorized its expansion to all public schools.

But even the programs offered by the state were not nearly enough to eradicate child hunger, and were ultimately scrapped under the vicious austerity of the 80s.

While the efforts of the Panthers were remembered fondly by those they helped, their programs made no decisive impact on the conditions of the working class in general. For all the Panthers’ honest efforts, the programs were less like a “survival kit” and more like a bucket with which to scoop out water on a sinking ship.

This is not to denigrate the efforts of the Panthers, nor to valorize the attempts of the capitalist state to alleviate the crises caused by their own system (which were short-lived anyways). Rather, the point is that no matter how hard we may try, workers simply cannot scrape together enough resources to truly improve their conditions under capitalism. The very reason for the survival programs’ existence was that the workers’ didn’t have enough.

Sharing the crumbs of our own exploitation

This is reflected by the fact that the Panthers often resorted to coercing small businesses to provide food donations, which led to controversy and divisions within local communities. Eventually they changed tactics and tried forging ties with local businesses to get more donations, and at a later point relied on donations from wealthy benefactors like celebrities. Both tactics pose serious dangers, either by unnecessarily alienating individuals who might otherwise be sympathetic, or making the party financially beholden to wealthy donors. The underlying issue is that the wealth necessary to genuinely improve workers’ conditions is not to be found among the workers themselves nor the petty bourgeois around them, but in the hands of the ruling class.

While Marxists support any reform which improves workers’ conditions, no matter how small, this means supporting the workers’ fight to win reforms at the bosses’ expense, not our own. Workers can win far more important and life-changing improvements by fighting for reforms than they can by engaging in mutual aid. Trying to meet workers’ needs with workers’ resources is like trying to make a pie feed more people by slicing it up differently. You cannot make the pie bigger, no matter how you cut it. At best, you could ensure that everyone gets an equally insufficient piece.

At this point, proponents of mutual aid may argue that while mutual aid may not be enough, it’s better than nothing—isn’t it worth it to make a difference, however small? It’s true that some workers will inevitably have a little extra money to spare or food to give, and it is only natural that they would want to give it to those in need. There is nothing wrong with this. As Trotsky once said, “The Marxists, of course, oppose not aid to the starving, but the illusion that a sea of need could be emptied with a teaspoon of philanthropy.” If we as communists were to take up mutual aid as a primary tactic, we would inevitably promote this illusion.

If we were to consistently mobilize donations and volunteers, encourage workers to help organize the provision of services, and so on, we would be telling the workers that their poverty is not the result of the ruthless exploitation of the ruling class, but their own inability to share the scraps well enough. Why should communists focus their efforts on encouraging workers to give up what little they have, when the capitalists who impoverished them in the first place are sitting on billions of dollars of hoarded wealth? The capitalists spend enough time nickel and diming the working class to death on the basis of the myth that there just isn’t enough wealth to go around. We cannot for a second help the capitalists in promoting this obscene lie. Our job is to ruthlessly expose the myth of scarcity, and teach workers that it is possible and necessary to seize the hoarded wealth and resources of the ruling class in order to meet society’s most pressing needs.

The desire to ‘give history a shove’

However, many proponents of mutual aid would agree that a revolutionary movement is needed, but would argue that mutual aid can be used to spark such a movement into action. This is one of Spade’s key claims: that mutual aid “mobilizes people, expands solidarity, and builds movements.” As proof, he argues that mutual aid has been “essential to every social movement.” But the mere fact that actions which can be called ‘mutual aid’ have taken place in many movements does not prove that they are what mobilized, expanded or built those movements. We cannot simply note that these actions played some role in past struggles, and conclude that they were essential to them. They played a role, yes—but what role exactly?

The labour battles which took place during the Great Depression provide a good starting point to answer this question. If mutual aid is “essential” anywhere, it would be essential here. Due to dire economic conditions, aid from the broader working class was often necessary for workers to stay on the picket lines. Workers were already struggling to feed their families, pay rent, and so on, even without the added difficulty of a strike. Further, unions were generally not flush with money to provide strike pay, given that the right to unionize barely existed and was in fact a key demand in many of the strikes of this period. In this context, securing resources like food, money, and medical care during strikes was highly important, and workers found many creative ways to do so. The organization of women’s auxiliaries, for example, became common practice across North America as women’s practical skills and political solidarity proved highly important in strengthening picket lines.

But even despite the exceptionally important role that the provision of aid played in these struggles, it was far from “essential.” What was essential were the militant, class-struggle ideas and tactics which led to these solidarity efforts.

The Teamsters’ Rebellion of 1934 provides an instructive example. The coal workers of Local 574 transformed their union from a weak, conservative “business union” into a force to be reckoned with, and even transformed Minneapolis’ reputation from that of a “scab’s paradise” to “a place of hope for those who toil.” In the process of their struggle, the coal workers drew in the town’s entire working class, who came to the aid of the Teamsters in remarkably varied and creative ways.

Teenagers on motorcycles acted as couriers, nurses and doctors provided medical care to picketers who’d been injured by cops, and the wives of strikers played a critical role in the women’s auxiliary cooking food, carrying out administrative tasks, and mobilizing even more women to get involved. Working class people across the town bought up the daily strike paper so eagerly that it became self-funding with no set price. One family even removed the banisters from their own home to use them as weapons against the cops trying to repress the strike. Unemployed workers, who made up a whopping one-third of the population, came to the aid of the strikers as well. The Teamsters encouraged them to join the picket lines and included them in the strike committees, which were the democratic decision-making bodies formed during the strike. In return for their solidarity, the Teamsters fought with the unemployed for public relief projects.

But none of this would have had even a chance of happening were it not for the Teamsters’ leadership, who convinced the workers that it was possible and worthwhile to try fighting the bosses in the first place. And this was no easy task. The conservative, bureaucratic clique which dominated Local 574 had bred indifference and mistrust toward the union. As a result, while a general mood of radicalization had begun taking hold among the workers, many of them did not believe that the union could help them achieve anything and were not looking to it as an avenue of struggle. So how did the Rebellion take place?

Farrell Dobbs, a worker who became a communist during the course of the struggle, stated that the key to the Teamsters’ success was “the presence locally of revolutionary socialist cadres who proved highly capable of fusing with the mass of rebellious workers and adding vital know-how in the struggle against the capitalist ruling class.” The most important of these revolutionaries were Carl Skoglund and Raymond Dunne. They organized mass meetings of workers and explained to them why they should join the union and fight for better wages, conditions, and proper union recognition. They faced numerous setbacks, including the betrayal of the workers by the bureaucrats, repression by the state, and conniving by the bosses. Time and time again, it was the revolutionary leaders’ ability to win the workers over to the correct course of action that proved decisive. The groundwork of the struggle was laid with innumerable mass meetings, speeches, articles, and individual conversations—in other words, ideas.

This is the key to the spirit of militancy and solidarity which characterized the Teamster Rebellion, and led to such an impressive mobilization of solidarity—the workers’ communist leadership gave them demands worth fighting for and showed them how to win, and the broader working class of Minneapolis saw their struggle reflected in that of the Teamsters. This explains the impressive mobilization of resources and aid during this period—the working class understood this mobilization as an investment in the struggle for demands that benefitted the entire class, including themselves.

A similar story is repeated across the strike battles of the 30s, and across history. Working class solidarity is often expressed in acts that could be called “mutual aid”—but the key is that it is expressed in these acts, not created by them. Historically, the provision of aid is not a decisive factor in mobilizing for the class struggle, but rather serves as an auxiliary to it. It can play a useful role in keeping the ranks of the struggle in fighting shape, but the success of the struggle depends ultimately on the leadership and its ideological preparedness. Providing aid to an army that is disorganized, demoralized and confused will not transform it into a fighting force.

It is understandable that young revolutionaries may look to past movements for elements that can be recreated in the here and now—like the mobilization of aid—to try to spark workers into action. But we will never recreate a successful movement by recreating its effects. In fact, we cannot “create” a movement at all. We can and must build a leadership that will give the workers the best chance of winning, as the communists of Local 574 did. But at the end of the day, it is capitalism itself that creates movements. Workers do not take to the streets or picket lines en masse due to the initiative of a few individuals. Mass movements are born out of the objective necessity of fighting against shrinking wages, worsening conditions, oppression, austerity, and so on.

The Narodniks, some of the earliest socialist revolutionaries in Russia, learned this lesson the hard way. After failing to rouse the peasantry into revolutionary action with words alone, they attempted to conduct “propaganda of the deed.” This meant executing attention-grabbing stunts like bombings and even the assassination of state officials, including the Tsar. The Narodniks wanted to “give history a shove,” assuming that the masses just needed the right spark to be convinced of revolution. Instead, the masses watched the Narodniks with confusion and suspicion. But a few years after the Narodniks had been disbanded and dispersed, the masses rose up in the revolution of 1905. They did so not because any group found just the right action to prompt them, but because the conditions of capitalism became unbearable and transformed consciousness on a mass scale.

Today, many mutual aid activists also want to “give history a shove,” and imagine that mutual aid projects can do just that, by giving workers something concrete and immediately beneficial to get involved in. Indeed, activist projects like these can and do draw in some individual workers. But they will never create a mass movement where it otherwise would not exist. Instead of engaging in the impossible task of “building” a movement out of nothing, we should focus on building a leadership that can guide the working class to victory in mass movements, and ultimately, revolution.

A penny for your loyalty

However, this is not to say that communists should simply sit back and wait for revolution. It is absolutely crucial that we actively participate in the class struggle in the here and now, and strive to earn the trust and authority of the working class. While the experience of class struggle is what ultimately brings workers to revolutionary conclusions, that experience alone is not enough to teach workers how to actually seize power and begin building a new society. For this, there must be a leadership armed with the lessons of past struggles and a scientific understanding of capitalism—which is to say, Marxism. Further, this leadership can only lead the workers to power if they have actively worked to earn the authority of the working class. Otherwise, they will remain isolated on the sidelines of the class struggle, no matter how good their ideas may be.

Many activists believe that mutual aid is the way to do this, arguing that workers will only listen to revolutionary ideas if they come with some kind of material help. The Black Panthers believed essentially this. As one Panther put it, “We didn’t preach to the people; we worked with them.” This implies that if communists focus primarily on explaining political ideas to workers, they will see us as “preaching” to them and reject our politics. But if we give them something, as the same Panther implies, they will be more amenable to our ideas.

This same idea is explained by BPP member Flores Alexander Forbes, referring to those served by the survival programs: “While we might not need their direct assistance in waging armed revolution, we were hedging our bets that if we did, they would respond more favorably to a group of people looking out for their children’s welfare.”

Forbes’ argument assumes that the working class chooses its leadership based on who has helped them the most. In a sense, this is true. But in the context of class warfare, the most important “help” comes from correct ideas that show the way forward for the struggle and guide the workers toward achieving their aims. It is not enough to be known for helping workers in their everyday life, because revolution is not an everyday matter. We must be known for our revolutionary ideas, and for our ability to apply them in the class struggle.

What communists need to earn is not simply popularity or goodwill, but political authority—and this can only be won with political ideas. Many proponents of mutual aid today argue that because the idea of communism is not popular among the majority of workers, we must win them over by meeting their needs. But this amounts to little more than bribery and shows a lack of faith in the working class. If we assume that the workers cannot learn except by being given resources or services, we risk watering down our ideas, and in turn, abandoning the one thing which really gives us the right to lead the working class. It’s true that most workers today are not revolutionary—but this will change! And when it does, nothing will matter more than our ideas.

Nine months before leading the working class to power, the Bolsheviks were just coming out of a period of intense repression in which open work among the masses was not possible. But with their bold and consistent revolutionary ideas, they had earned such a degree of political authority among the workers that they were able to leap into action at the soonest possible moment, and take power shortly after. In the period before World War I, the Bolsheviks had won the support of four fifths of the organized working class. With their papers, leaflets, slogans, and agitation, they had embedded their ideas in the hearts and minds of hundreds of thousands of workers. The result was that Bolshevism lived on in the consciousness of the working class even when the party could conduct only the most limited work in the movement, and it is for this reason that they were able to take power so shortly after coming out of underground work.

Evidently, the workers did not feel “preached to” by the Bolsheviks, or if they did, they did not mind the preaching. On the other hand, had the Bolsheviks withheld their ideas and hid them behind acts of service, they would have failed to prove themselves as capable revolutionaries and would not have earned the right to lead the workers.

If all the revolutionaries are doing mutual aid, who’s building the revolutionary party?

At this point, even if one agrees that mutual aid cannot significantly improve the conditions of the working class, build a movement, or earn political authority, the question might be asked: what’s the harm in doing it anyways?

In some cases, when the need for aid crops up as an organic phenomenon in the class struggle, it can be appropriate for revolutionaries to support it. But as with any other tactic, it must never be prioritized over the building of the revolutionary party and the defense of revolutionary ideas. This is the decisive factor in overthrowing capitalism, which means that communists must think of each activity and tactic as a calculated investment in that final goal.

If communists prioritize mutual aid in principle simply because it is a “good thing to do,” they will inevitably deprioritize the building of the revolutionary party. There are only so many hours in a day, and each activity we choose to take on means choosing another not to take on. Communists have a responsibility to decide which tasks are essential to the overthrow of capitalism and which are not. This is an especially crucial consideration when it comes to mutual aid, because trying to make immediate changes in the workers’ conditions takes an enormous amount of time, energy and effort. An anecdote from a Panther in the Philadelphia section illustrates this well:

“The offices were like buzzing bee hives of Black resistance. It was always busy, as people piled in starting at its 7:30 A.M. opening time and continuing ’till after nightfall. People came with every problem imaginable, and because our sworn duty was to serve the people, we took our commitment seriously. When people had been badly treated by the cops or if parents were demanding a traffic light in North Philly streets where their children played, they came to our offices. In short, whatever our people’s problems were, they became our problems.”

(Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, p. 180)

This description of nonstop practical activity begs the question: while the Panthers were responding to the endless problems of workers, who was building the revolutionary party that could actually attack the root of those problems? At what point would the workers’ immediate conditions be improved enough that attention could be focused on taking power, and when that time came, where would the party be? Ironically, by focusing so strongly on serving the people, the Panthers ultimately ended up depriving them of what they needed most: a strong revolutionary party grounded in Marxist theory.

In 1892, when a famine was gripping the workers and peasants of Russia, liberal politicians and state officials engaged in various activities providing aid to those in need. Leon Trotsky, who led the October Revolution alongside Lenin, warned his comrades against throwing their time into these activities:

“If a revolutionary occupies a place in the legal committees and refectories that rightfully belongs to a member of the zemstvos [local government institutions] or to a state official, who will occupy the place of the revolutionary in the underground action?”

Here, Trotsky is pointing out that if the revolutionaries did not join the legal committees or serve food to the hungry (“refectories” refer to communal dining halls), the bourgeois politicians would do it instead, and the same result would be achieved. But if the revolutionaries neglected to build the party, nobody else would do it. Therefore, each time a communist invests their efforts into an activity that takes them away from the task of building the party, they are weakening the working class’s chance of overthrowing capitalism.

The working class is an oppressed class. It is inevitable that there will constantly be more issues to attend to and wounds to bandage—as exemplified by the Panthers’ around the clock activity—because we live under capitalism. To try to bandage each and every injury sustained by the working class, literal and figurative, is simply impossible. If this were not the case, we wouldn’t need a revolution—but it is, and we do. This is why we must raise our sights, and remain focused on building a communist party that can lead that revolution to victory.

‘The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves’

Many communists, even if they agree with all of the above arguments, may find themselves still compelled by a feeling of moral obligation to help the working class right now. This is only natural, given the acuteness of the capitalist crisis and the suffering we witness in our everyday lives. But being a communist means dedicating yourself to a cause far greater than your personal moral feelings. We are not just people who like helping workers because it feels good. In fact, our job is not to help workers at all—at least not in the narrow sense of providing goods and services. Communists must strive to lead the working class, not just help it. This difference is not semantic. It is the difference between viewing the working class as passive recipients of aid, or as the active protagonists of history.

Marx explained long ago that “the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves.” What this means is that we cannot step in and meet workers’ needs for them, nor can we liberate them ourselves. Only the workers themselves, firmly united under a revolutionary programme, are strong enough in numbers and social weight to overthrow the old system and begin building a new one. Therefore, we must take every opportunity to raise the confidence of the working class in its ability to do so. This means helping them to break from leaders who encourage them to make peace with the ruling class, and showing how their interests can be fulfilled only by relying on their own forces. It also means helping them to see the necessity of overthrowing capitalism entirely, rather than relying on compromises and half-measures. The confidence and class-independence gained through this process is critical for ensuring that the working class becomes prepared to take power when the opportunity arises.

But if we focus all of our efforts on “helping” workers in the narrow sense, we teach them that their problems can be solved by receiving aid or aiding one another, rather than actively entering into struggle with the ruling class. And despite the claims of many mutual aid proponents, simply providing workers with aid does not teach them to question the limits of capitalism. Spade argues that mutual aid “exposes” the inadequacy of capitalism by demonstrating that the system has failed to meet our needs. But do those unmet needs not prove themselves, in the very clear language of unpaid bills, rising rent and hungry bellies? Workers know very well that their needs are not being met. In fact, the crisis of capitalism is so obvious that even the most conservative workers understand that something is fundamentally wrong with the status quo. Workers do not need to be taught that things are bad. What they need to learn is the root cause of the crisis facing them and how to abolish it, and this is where the communists come in. Our job is to shout from the rooftops that the capitalists have driven us into the present crisis, that they have no ability to get us out of it, and that the working class can and must build a new society without these parasites.

But if someone were to tell the billionaires that instead of calling for the overthrow of the system, the communists were focused on small acts of service and “helping” the workers, they would laugh with relief. Simply following behind the ruling class and quietly cleaning up its trail of devastation poses no threat to the status quo. It does not expose the role of the capitalists in creating that devastation in the first place, nor does it give the working class a chance to feel its strength or learn how to fight the enemy. It leaves the enemy untouched, and the working class on the sidelines.

But this does not mean communists take no interest in improving the conditions of the working class under capitalism. In fact, communists must strive to be the most steadfast defenders and leaders of any struggle for reforms, no matter how small. We are not opposed to aiding the workers in improving their conditions; we are only opposed to encouraging them to view their struggles as an apolitical matter which can be solved by what essentially amounts to charity. We believe that the workers should take what they need from the capitalists who took it from them in the first place. For every issue which mutual aid may be used to patch up, there is a militant, class-based demand which could attack the issue at its root, make the ruling class pay, and improve the conditions of the working class in a far more important way.

The Bolsheviks provide a positive example of how to use such demands. In 1906, the Russian working class found itself in dire conditions. The tsarist government was getting its revenge against the workers for the revolution of 1905 by violently repressing communists and the oppressed, while the bosses waged economic terrorism with constant sackings and lockouts. In this context, the struggle of unemployed workers took on important significance, and the Bolsheviks intervened in this struggle with great success—not by passively providing aid to the unemployed, but by actively bringing them into the struggle.

Their first step was to form an Unemployed Council, which was then linked with the soviets—the democratically elected councils of workers formed during the 1905 revolution. Connecting the soviets to the Unemployed Council was crucial for giving the unemployed workers a fighting chance at securing better conditions. As an isolated layer without the ability to strike, the unemployed would have had little power. They needed the aid of the workers in the factories. When Lenin first heard of the new Unemployed Councils, this was his main concern:

“Through this organization alone, you cannot influence the bourgeoisie; you will not be strong enough, and the unemployed workers themselves may not be able to develop this work on a broad proletarian class basis. Therefore, you must immediately extend the Unemployed Council to include representatives of those employed in all the factories and mills of St. Petersburg. You must now begin to agitate in the factories and mills for this purpose, and immediately arrange for the election of these representatives.”

The Bolsheviks followed this advice, organizing the workers in the factories to enter into the Unemployed Council and offer their support in the struggle. But the relationship between the workers in the factories and the unemployed was not a one-way street, in which the workers gave charity to the unemployed out of mere sympathy. Indeed, the workers did organize voluntary collections at each meeting, and the St. Petersburg Soviet even adopted a resolution to donate one per cent of wages to the unemployed. But these donations did not have a decisive effect. They were only an auxiliary to the goal of advancing the conditions of the unemployed in unison with the struggle of the working class as a whole.

This is reflected in the petition created by the Unemployed Council, to be presented to the local government. Speakers were sent to all the main factories to talk to workers at shift changes and on lunch breaks to mobilize support, which the workers enthusiastically gave. The petition read:

“Owing to unemployment, numberless workers’ families are now without bread. The workers do not want charities, or dole. We demand work. The masters refuse to give us work. They say they have no contracts. But the City has contracts and can provide work for the unemployed. We think that the way the City disposes of the public funds is scandalous. Public funds should be used for public needs and our need today is—work. Therefore, we demand that the City Duma immediately organize public work for all the needy. We demand not charity, but our rights, and we will not be satisfied with charity. The public work that we demand must be started immediately. All the unemployed of St. Petersburg must be allowed to do this work; every unemployed worker must receive an adequate wage. We have been delegated to insist on the fulfilment of our demands. The masses who have sent this will not be content with less. If you do not accede to our demands we will report your refusal to the unemployed and then you will not have us to deal with, but those who sent us, the masses of unemployed.”

These are sharp demands which clearly advance the struggle of the working class as a whole, not only the unemployed. Nobody could confuse these demands with requests for charity—as is made explicit in the petition itself—and they correctly force the ruling class to foot the bill for the crises they’ve caused, not the workers.

The town councillors were frightened enough by the united anger of the workers and unemployed to concede every last demand. While they went on to revoke many of these concessions later, the improvements which remained helped the working class get by in a dark period of reaction. Certainly, the struggle achieved far more than only relying on donations would have. The unemployed also returned the solidarity shown to them by mobilizing financial donations for the striking St. Petersburg workers shortly after.

Most importantly, the Bolsheviks were able to use this struggle as an avenue for advancing revolutionary ideas. By guiding the working class to improve its conditions on the basis of its own strength, they helped the workers gain confidence and class independence, breaking them away from the bourgeois liberals. This is the kind of work that laid the basis for the Bolsheviks’ victory in 1917.

Not help, but liberation—build the revolutionary party!

There will always be pressure to “do something” in the here-and-now, whether in the form of mutual aid or anything else. To feel this pressure is only natural—who could help but desire action? Millions of workers around the world face nightmarish conditions day in and day out, and the crisis is only getting worse. Capitalism is becoming more and more incompatible with human life itself.

But this is precisely why we are communists, and why we must build a revolutionary party that can overthrow the system that causes such universal suffering. It would be a grave mistake to put our heads down and focus on small, ‘practical’ activity at precisely the moment when the workers and youth are beginning to raise their sights and see the necessity of fighting for a better future. Our responsibility is to urgently and steadfastly aid them in this process, by extending their fighting confidence and connecting their class instincts to the revolutionary perspective.

This is a very different task—and a far more important one—than merely ‘helping’ the workers. Our task is to help them only insofar as we help them understand how to liberate themselves, on the basis of their own strength. Understanding how to do this requires us to question our initial instincts and feelings, and take up a thorough study of revolutionary theory and history. This may feel counterintuitive, compared to the urge to leap into action in the first way we can think of. But it is how one truly becomes a communist—someone who can raise their sights above the here-and-now and toward the future revolution, and help the working class do the same. As the Russian revolutionary Plekhanov put it:

The careful, scientific study of social phenomena demands much composure and, if you will, even a cold dispassion. Nevertheless, it can only create a firm basis for passionate action of the selfless political fighter, only it can save him from despair, only it can develop such revolutionaries as will not lose heart as the result of individual failures or become confused by the temporary successes of enemies. In short, only it, only it alone creates unbreakable and invincible activists, revolutionaries in logic and in feeling.