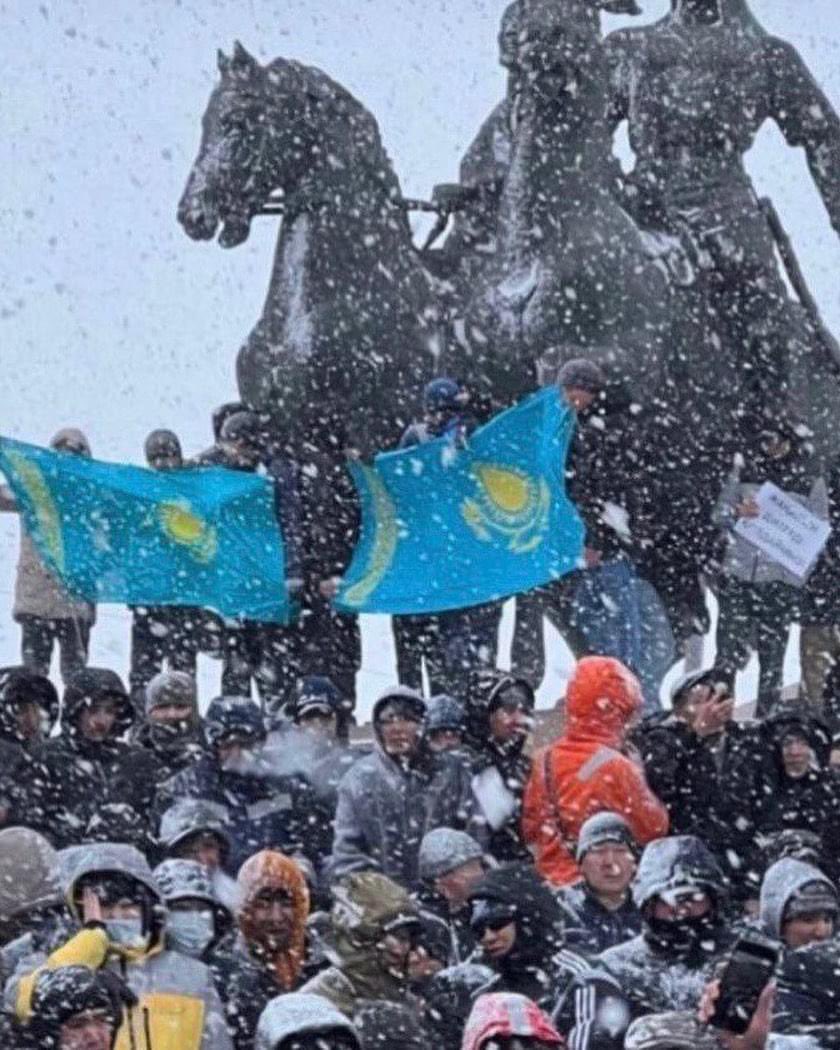

Yesterday, Kazakhstani army and security forces backed by Russian special forces moved in to forcibly put down what has become the biggest mass movement in Kazakhstan since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

On Thursday 6 January, street fighting took place in several large cities of Kazakhstan after the authorities declared a state of emergency and moved the army in to re-establish its grip on power. In a message designed to shock and provoke, a police spokesperson told state news that “dozens of attackers were liquidated”. There have been reports of hundreds of wounded and thousands arrested. Appearing on TV today (Friday), a pompous president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said he personally gave the order to security forces and army to “open fire with lethal force” against what he called “bandits and terrorists”.

It is clear that the state apparatus is moving swiftly and violently in order to take back control, which appeared to be slipping out of its hand in the past few days. All airports, roads, squares and other key points of communication and transport, which had previously been taken over by protesters, are now firmly back in the hands of the state.

In the absence of any clear leadership and organisation, such overwhelming force appears, at least for now, to have beaten back the protests, which had engulfed all the major cities of the country for the past week. The movement took on a semi-insurrectionary character after it overran airports and government buildings in major cities, and there were indications of fraternisation amongst police and protesters. Without a clear plan of where to go from there, however, initiative swung towards the counter-revolution, which managed to reorganise and strike back with a combination of concessions and brute force.

Faced with the powerful movement, the state was initially forced to give a series of wide-ranging concessions, such as the reduction of gas prices in the Mangystau region and the introduction of state regulation of petrol, diesel, natural gas and staple food products as well as the dismissal of the entire government. This had raised the confidence of the movement and spurred it forward while the state forces were slowly disintegrating. Tokayev appeared to be reacting to events, leading to widespread demoralisation and disorientation within the ranks of the state apparatus in particular.

On Thursday however, Tokayev – who had until then operated as a de facto caretaker president, with former President Nursultan Nazarbayev retaining real power in the background – stepped forward and took the reins. He dismissed the government and pushed aside Nazarbayev, announced a state of emergency, and called on the assistance of Russian troops (under the cover of the Collective Security Treaty Organization). This bold and confident move appears to have galvanised the forces of the state and buoyed them for the offensive we have witnessed in the past 24 hours.

Meanwhile, with many of the initial demands of the movement having been granted and no new and clear objectives being put forward, some layers began vacillating. This trend was strengthened by the looting and senseless violence, which was undoubtedly promoted and orchestrated for the most part by the state. Under these conditions, and faced with the prospect of fighting state repression without any clear organisation or programme, a layer would have retreated, leaving the most radical elements potentially isolated on the streets.

But while the streets have been cleared in some places, such as Almaty and the capital Nursultan, in other places such as Zhanaozen and Aktau, protests continue and have renewed today. It cannot be ruled out that once the movement has overcome its shock, it will be radicalised and take new steps forward. Whatever happens, this is by no means the end of the Kazakhstani revolution. On the contrary, this is only the beginning.

Instability ahead

What we are witnessing is a turning point in the history of Kazakhstan. The country, which for years had been highlighted by the bourgeois as a model of stability, is now entering a new stage of instability, crisis and class struggle. The strategy of the regime will be to beat back the movement through a combination of violent repression and economic concessions.

Kazakhstan has some of the largest reserves of chromite, wolfram, lead, zinc, manganese, silver and uranium in the world. It also has significant reserves of bauxite, copper, gold, iron ore, coal, natural gas and petroleum. On the basis of these reserves it has also built a significant sovereign wealth fund that it can dip into in order to give certain social and economic concessions.

However, this will not be enough to buy sustained stability. These resources are dependent on a world economy that is in a dire state. In 2014, when oil and mineral prices began declining as a result of slowing economic growth in China and the West, Kazakhstan’s GDP growth fell from 4.2 to 1.2 percent. Once the pandemic hit, the situation worsened, as prices increased and access to welfare declined for the poorest. In the next period, the world economy will face new downturns, which will put additional pressures on Kazakhstan’s economy, meaning that the ruling class is bound to attack living standards in order to maintain its own position.

For two decades the Kazakh regime, led in a Bonapartist manner by Nursultan Nazarbayev, could maintain relative stability on the basis of an economy that was growing quickly and a relative growth of living standards – at least for some parts of the population. That era, however, is finished. If it was not clear last week, then certainly after last night, the regime has been thoroughly discredited and will increasingly be forced to rely on brute force to maintain itself, a fact that in turn will push even more layers into opposition. Thus, the “order” that Tokayev has so proudly proclaimed in Nur-Sultan and Almaty, will form the basis for a new period of instability and class struggle.

A colour revolution?

Some people on the left have been quick to call the past week’s movement in Kazakhstan a ‘colour revolution’, orchestrated by the west as a part of a plot to isolate Russia. According to this line of opinion, what we are witnessing is similar to the reactionary Maidan movement in Ukraine, which was essentially a movement controlled by far-right and fascist elements egged on by Washington. That, however, is a superficial comparison that ignores the facts on the ground in Kazakhstan.

If anything, the movement we have witnessed in the past few days has been remarkable for the limited presence that we’ve seen of liberal and petit-bourgeois elements. Unlike the protest movements between 2018 and 2020, last week’s protests had a real revolutionary character and were begun by workers, who played a key part, as well as by poor unemployed and lower-middle-class elements.

The starting point and initial epicentre of the movement was in the western region of Mangistau, the heartland of large oil companies and home to a large and powerful industrial working class with fighting traditions. The region is home to Zhanaozen, a town in which tens of thousands of oil workers went on strike in 2011, and essentially occupied the city for seven months before they were brutally repressed by the armed forces. It is clear that this experience played an important role in the movement today, which to a large degree was based on the traditions of struggle in that region.

This impressive development of the movement over the space of a few days was explained very well in a statement by the Socialist Movement of Kazakhstan, which we will quote at length:

“There is a real popular uprising in Kazakhstan now. From the very beginning the protests were of a social and class nature; the doubling of the cost of liquefied gas on the stock exchange was only the straw that broke the camel’s back. After all, the events began in the same way in Zhanaozen, on the initiative of oil workers, which became a kind of political headquarters of the entire protest movement.

“The dynamics of this movement are indicative. Since it began as a social protest, then it began to expand, the labour organisations used their rallies to raise their own demands for a 100 percent increase in wages, cancellation of unreasonable production targets, improvement of working conditions and freedom of trade union activity. As a result, on 3 January, the entire Mangystau region was engulfed in a general strike, which spread to the neighbouring Atyrau region.

“It is noteworthy that already on 4 January, the oil workers of the Tengizchevroil company, 75 percent of which is controlled by American multinationals, went on strike. It was here that 40,000 workers were laid off in December last year and a new series of layoffs was planned. These workers were subsequently supported during the day by oil workers of Aktobe and West Kazakhstan and Kyzylorda regions.

“Moreover, in the evening of the same day, strikes began of miners from the ArcelorMittal Temirtau company in the Karaganda region, and copper smelters and miners from the Kazakhmys corporation, which can already be regarded as a general strike across the entire national mining industry of the country. And there were also demands for higher wages, a lower retirement age, the right to run their own trade unions and conduct strikes.

“At the same time, indefinite rallies had already begin on Tuesday in Atyrau, Uralsk, Aktobe, Kyzyl-Orda, Taraz, Taldykorgan, Turkestan, Shymkent, Ekibastuz, in the cities of Almaty region and in Almaty itself, where the closure of streets resulted in an open clash of demonstrators with the police on the night of 4-5 January, as a result of which the akimat [provincial government] of the city was temporarily seized. This gave and excuse for Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to declare a state of emergency.

“It should be noted that these speeches in Almaty were attended mainly by unemployed youth and internal migrants living in the suburbs of the metropolis and working in temporary or low-paid jobs. Attempts to calm them down with promises to reduce the price of gas to 50 tenge, separately for the Mangystau region and Almaty, have not satisfied anyone.

“The decision of Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to dismiss the government, and then remove Nursultan Nazarbayev from the post of chairman of the Security Council, also did not stop the protests. Mass protest rallies already began on 5 January in regional centres of Northern and Eastern Kazakhstan where none had previously broken out – in Petropavlovsk, Pavlodar, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Semipalatinsk. At the same time, attempts were made to storm the buildings of regional akimats in Aktobe, Taldykorgan, Shymkent and Almaty.

“In Zhanaozen itself, workers formulated new demands at their indefinite rally, including the resignation of the current president and all Nazarbayev officials, the restoration of the 1993 Constitution and related freedoms to form parties, the right to create trade unions, the release of political prisoners, and the cessation of repression. A Council of Elders was immediately created, which became an informal authority.

“Thus, the demands and slogans that are now used in different cities and regions were broadcast to the entire movement, and the struggle received political content. Attempts are also being made on the ground to create committees and councils to coordinate the struggle.”

What we see very clearly from the above is the enormous role of the industrial working class of Mangystau, which essentially led the movement and imbued it with its own proletarian political programme and methods of organisation and struggle. Meanwhile, the vague democratic and nationlist demands of the western-backed liberal opposition remained peripheral at best.

In a very interesting interview published on Zanovo-media, Aynur Kurmanov – one of the leaders of Socialist Movement of Kazakhstan in exile – answers the claim that this was a conspiracy orchestrated by western powers:

“This is not a Maidan, although many political analysts are trying to present it in this way. Where did such amazing self-organisation come from? It is based on the experience and traditions of the workers. Strikes have been shaking the Mangistau region since 2008, and the strike movement began back in the 2000s. Even without any input from the Communist Party or other leftist group, there were constant demands to nationalise the oil companies. The workers simply saw with their own eyes what privatisation and foreign capitalist takeover were leading to. In the course of these earlier demonstrations, they gained enormous experience in terms of methods of struggle and solidarity. Living in the wilderness made people stick together. It was against this background that the working class and the rest of the population came together. The protests of the workers in Zhanaozen and Aktau then set the tone for other regions of the country. Yurts and tents, which protesters began to put up in the main squares of the cities, were not at all taken from the ‘Euromaidan’ experience: they stood in the Mangistau Region during the local strikes last year. The population itself brought water and food for the protesters.”

Not only are the workers of the Mangystau region not in cahoots with US imperialism, they have a rich tradition of fighting western-based multinationals! This is not to say that there are no bourgeois ‘liberal’ and nationalist organisations that are trying to capitalise on the movement, but one thing is certain: they did not start it and they are not in control of it.

Kazakhstan, Russia and the West

It would be incorrect to present Kazakhstan as a country dominated by Russia. The Kazakhstani regime of Nazarbayev spent 30 years playing a game of balancing between Russia, the US, China, and even Turkey, playing each power against each other in order to get the best deal for itself. In fact, it is not Russia, but the US, owing to the investments of Chevron and ExxonMobil, that ranks first among the foreign investors in Kazakhstan. Chevron itself is the largest investor in Kazakhstan.

Meanwhile, the majority of the vast overseas wealth of the Kazakhstani establishment is stored in the West and in the Gulf countries. Nursultan Nazerbayev’s main domestic policy was not anti-western, but anti-Russian Kazakh nationalism, which has led to a dangerous chasm between the Kazakh and Russian speakers of the country.

There is no supposed plot for US imperialism to enter Kazakhstan – it is already there and is profiting well from its presence! So too is the ruling class of Kazakhstan. This relationship was clear from the meek statement of the US State Department spokesperson, Ned Price, who said that the US “… hope[s] that the government of Kazakhstan will soon be able to address problems which are fundamentally economic and political in nature”. Price went on to emphasise that the U.S. is a “partner” of the Central Asian nation!

US Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, who spoke with Kazakhstan’s Foreign Minister Mukhtar Tileuberdi, “reiterated the United States’ full support for Kazakhstan’s constitutional institutions and media freedom and advocated for a peaceful, rights-respecting resolution to the crisis.” These are not the words of a belligerent imperialist power trying to muscle its way into Kazakhstan, but of an imperialist power that is nervous about the future stability of that country, and the ability of the Kazakhstani regime to guarantee the security of its interests. If anything, it reveals the impotence of the West to intervene, even if it wished to do so.

Meanwhile, Russia is keeping a nervous eye on developments in Kazakhstan. Similar to the recent mass movement in Belarus, the Kazakhstani movement poses a threat to the stability of Russia, where the masses suffer under similar conditions. Thus, the intervention of Russian forces has an important domestic purpose. This does not mean, however, that Putin will not demand a certain ‘payment’ for saving the Kazakhstani regime, just as he demanded obedience from the Belarussian regime. Nevertheless, the US will be powerless to do anything about this. Rather, it is likely to become increasingly dependent on Russia to protect its interests in the country.

What way forward?

What we are witnessing is not a colour revolution, a CIA conspiracy, nor a clash between different sectors of the Kazakhstani ruling class. It is a genuine revolutionary movement of the workers, the youth, the poor and dispossessed.

It is based on the programme and organisational methods of struggle developed by the most advanced layers of the industrial working class. These methods (strikes, mass rallies, etc.), and a programme of economic, social and democratic demands were highly effective, as demonstrated by the speed with which the movement advanced, threatening to bring down the whole edifice of the state within four days.

Nevertheless, the question of leadership and organisation remains the main weakness of the movement. Without a national organisation of the working class, the movement was incapable of extending the strikes to the level of a national, revolutionary general strike; or of responding to the swift manoeuvres of the regime. It also failed to organise a systematic campaign to decisively win over the Russian speakers, who make up just under 20 percent of the population.

In the next period, particularly if we witness a general withdrawal of the broader layers of the masses from the streets, bourgeois liberal elements will undoubtedly try to hijack what remains of the movement. Given the lack of any solid national workers’ party and leadership to counter their manoeuvres, they may even succeed. However, the struggle between these different tendencies in the movement is not determined in advance. Characterising the present movement as a reactionary one now amounts to capitulating in such a struggle at its outset. Instead, what is necessary is for the most advanced revolutionary elements to draw the lessons from these events, and to begin the struggle to build a revolutionary leadership, based on the most advanced elements of the working class and the youth.

Here, we have to disagree with Aynur Kurmanov, whom we quoted above, who seems to suggest that, even if liberal bourgeois opposition forces come to power, this could somehow still benefit the working class. In the above interview, he says:

“The existing left-wing groups in Kazakhstan are more like circles and cannot seriously influence the course of events. Oligarchic and outside forces will try to appropriate or at least use this movement for their own purposes. If they win, the redistribution of property and open confrontation between various groups of the bourgeoisie, a ‘war of all against all,’ will begin. But, in any case, the workers will be able to win certain freedoms and get new opportunities, including for the creation of their own parties and independent trade unions, which will facilitate the struggle for their rights in the future.” (our emphasis)

We must warn against any illusions in this respect. The working class and revolutionary movement cannot in any way be seen to promote the coming to power of bourgeois liberal forces. The role of the liberal ‘democratic’ opposition is to dilute the class nature of the movement and the class contradictions in society in general. As the experience of the National League for Democracy in Burma, the Maidan movement in Ukraine and the experiences of countless revolutions show, the role of the liberal opposition is to save the system. They are the enemies of the masses, and as revolutionaries we must fight against giving any concessions to these forces. Any collaboration or even willingness to collaborate with such reactionaries will discredit and undermine the movement. The coming to power of a different gang of capitalist oligarchs would not solve any of the problems facing the working masses. Regardless of their pretence to be ‘democratic’ and ‘liberal’, there’s no guarantee whatsoever that in coming to power these gentlemen (many of whom were part of the Nazarbayev regime not so long ago) would not implement the same measures and use the same methods of banning left-wing political parties and trade unions, jailing left-wing and worker activists, and responding to mass mobilisations with repression.

The mass of workers and poor can only rely on their own strength to finish the Kazakhstani revolution. In a matter of days, on the basis of radical, proletarian methods and demands, they have achieved more than any liberal NGO could have dreamt of achieving in the past decade. They have won a string of victories and pushed out the sitting government and the old dictator. Only on the basis of deepening this struggle can they prepare to finish the job and bring down the whole rotten regime.