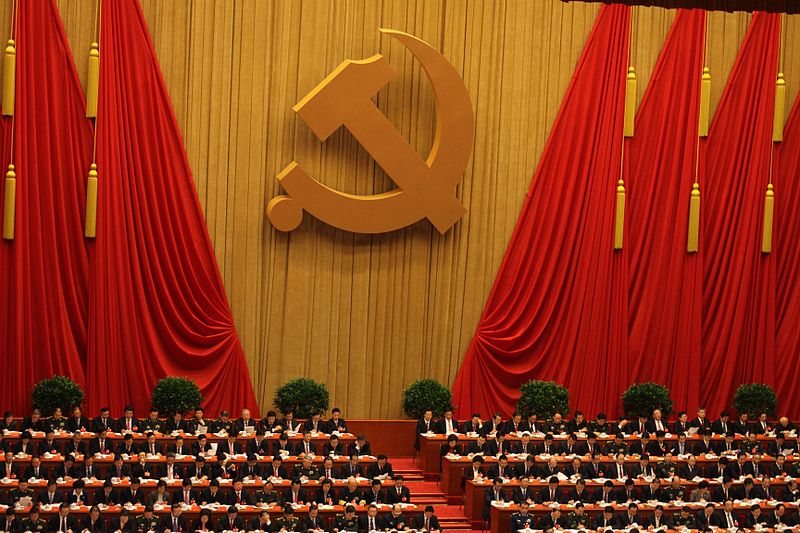

In July 2021, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrated the 90th anniversary of its founding with a blitz of propaganda boasting about how the party’s rule had led to a prosperous, confident and happy China. Yet a year later, the discontent among the Chinese masses towards the regime has reached unprecedented levels, while those at the top of the byzantine party-state bureaucracy are showing clear differences about how to proceed. What does this reveal, and what is its significance for Marxist revolutionaries?

Large and urgent call

The present crisis in the Chinese bureaucracy is betrayed by uncharacteristic conduct among the officialdom. The most unusual development has to be the ‘National Teleconference on Stabilising the Economy’, headed by Premier Li Keqiang. This enormous teleconference included officials from the top of the central government down to county-level bureaucrats. The nature of the conference was characterised by state media Global Times as “unprecedented” and has colloquially been referred to as the “One Hundred Thousand Cadre Conference” (十万人大会).

Moreover, Premier Li Keqiang used an uncharacteristically candid tone for a CCP bureaucrat to report on the economic prospects facing the world’s second-largest economy:

“We’ve weathered the sudden shock in 2020. Now some comrades are saying that the present situation in some ways and on some level is possibly worse than 2020. It may be true for certain aspects of certain sectors. But overall we have two-and-a-half years of experience. We must have confidence. In face of a sudden bout of hardship, we even achieved the only positive economic growth in the world.“Now we must again overcome the challenge ahead by realising positive growth and reducing unemployment in the second quarter. I won’t speak on fiscal policies to you all here. The Central government will figure something out for fiscal policy. You secure yourselves in the regions. Once we’ve achieved these two items, we could then work to complete this year’s tasks in social development. One of the foundations of [achieving this success] is the decisive deployment of timely measures. Every one of you should [therefore] be able to see the necessity of holding this conference today.”

The conference itself did not unveil anything brand new. Rather, its aim was to urge the regional governments to swiftly implement the 33-item stabilisation policy that the central government had issued in May. The policy dictated both central and local governments to implement Keynesian measures such as tax rebates, deficit spending, debt issuance, and other measures to stimulate consumption and investment.

As Guosheng Securities analyst Xiong Yuan observed in Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao, the conference was about pushing “for implementation and enhancement of oversight” on regional authorities, not only because of the difficult situation, but also because “in the past months, there were many policies issued that were not enforced on the ground.”

While there have always been gaps between the Centre’s dictates and their implementation in the regions, the recent harsh lockdown measures against the outbreak of the COVID-19 Omicron variant have severely widened this gulf. Shanghai was the most illustrative example. There, the clash between local authority measures and the dictates of the Central government resulted in hasty and ever-changing measures, economic chaos, and widespread discontent. Now, against the economic fallout from the lockdowns, the top officials in Beijing have issued orders right to the faces of officials down to the county level to fall in line, to avoid risking similar inconsistencies that might further destabilise the situation.

But the root of the economic turmoil is not inconsistent enforcement of policies by the state at any level. Rather, it is rooted in the organic crisis of Chinese and world capitalism. No amount of ‘commandism’, which is rising to new heights under Xi Jinping, will be able to sort out the deeply unequal and unbalanced development between the regions – and, of course, the growing inequality between classes.

Deeply indebted provinces, such as Qinghai, Heilongjiang, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia – which have spending-to-income differentials exceeding 300 percent as of 2020, and which have seen efforts to reduce their debts – are going to be caught between a rock and a hard place in the face of the Centre’s demand for Keynesian measures. Wealthier jurisdictions such as Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, will in turn be economically burdened by the effort of the Centre to support the poorer regions, while shoring up problems of their own.

These problems express an already existing reality of Chinese capitalism. The destruction of the planned economy has left many provinces impoverished, while wealth and resources concentrate in a few places where the capitalist class focuses its investments for profit and exploitation. This imbalance, compounded by the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdowns, could produce serious social instability for the entire CCP regime. The only thing the CCP regime, which bases itself on a market economy, can do is to demand their subordinates engage in Keynesian deficit spending measures. But the end result can only be to push many provinces closer to a kind of fiscal catastrophe like that faced by the city of Hegang, Heilongjiang earlier this year, where the local government had to implement a hiring freeze, and even clawed back bonus payments to government clerks.

Yet the conflict isn’t between the Centre and the regions alone. At the very top of the party, differences have begun emerging for the world to see.

Xi and Li: a tale of two interests

Since the 19th Party Congress of the CCP in 2017, Xi Jinping has cemented himself as the undisputed supreme leader of the country, with a degree of power only rivalled historically by Mao. Over the years, he has progressively eliminated his rivals and upended many of the collective leadership arrangements that Deng Xiaoping had put in place, including eliminating presidential terms, in a thinly veiled bid to make himself ruler for life. The 20th Party Congress this year would be a formal confirmation of Xi’s reign should he succeed in being ‘elected’ as General Secretary, and later President, for an unprecedented third term. Throughout this time, Xi not only has not faced a credible challenger, but he seems to have secured the entire bureaucracy’s complete obedience to his every diktat – that is, until now.

As Shanghai’s chaotic lockdown started to yield serious economic consequences, various parts of the bureaucracy began quietly questioning the efficacy of China’s stringent ‘Zero COVID’ policy. It is true that the regime’s strict earlier measures had prevented the massive outbreaks and deaths seen elsewhere in the world. But as the rest of the world began adopting the “living with COVID” stance, allowing the virus to roam freely within the global population, ‘Zero COVID” measures that decreed rapid lockdowns and daily PCR tests for millions of people became not only futile, but unsustainable for the world’s second-largest economy.

Yet relenting on ‘Zero COVID’ would also be a blow to the regime’s prestige among the Chinese masses. It would damage the CCP’s previous claim that China’s success in containing the virus was solely down to the “superiority” of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”, and above all to Xi Jinping’s leadership. Xi declared this to be unacceptable in the Politburo Standing Committee meeting of 5 May. Through the People’s Daily report on the meeting, Xi declared:

“The pandemic measures established by the Party Centre must be thoroughly, fully, all-sidedly understood. All insufficiencies in understanding, preparation and implementation [of the measures] must be stubbornly overcome. All attitudes of disregard, indifference to, and self-righteous thoughts [against the line] must be overcome. With a consistent and clear mind and insistence on the general line for ‘dynamic Zero COVID’, [we must] implacably struggle against all distortions, skepticisms and rejection towards our country’s pandemic measures.” (Our emphasis)

With these lines, Xi Jinping made clear that the pandemic measures must be maintained at all costs, including the heavy economic cost.

But this declaration was then contradicted by Li Keqiang’s convocation of the ‘One Hundred Thousand Cadre’ meeting, which emphasised the need to maintain economic growth, which implies the need to relent on ‘Zero COVID’ measures.

In outline, this divergence is between two props on which the CCP has maintained its capitalist dictatorship up to this point: on the one hand, it must deliver continuous economic growth for the masses; and on the other, it must maintain trust in a highly centralised party-state. In previous times, these two things went hand-in-hand. But with the sudden emergence of the virus, the two legs started walking in different directions.

That Xi falls on the side of maintaining the state’s prestige at all costs is only natural. He is the public face of the entire party-state bureaucracy, and therefore is on the receiving end of any ire that the masses may feel if a relaxing of measures results in an outbreak (and the kind of consequences seen in the West). This is plausible, as China’s vaccines have proven to be inferior to those of the West, especially against the Omicron variant. Such an outcome could seriously threaten Xi Jinping’s path to an unprecedented third term of supreme leadership.

The discord between these two considerations has resulted in inconsistent policies to date. At times, lockdowns seem to be quickly enforced but are later relaxed, while the masses continue to get mixed messages in terms of when the lockdowns will end. There are no clear signals or roadmaps as to how the government would finally face up to the reality that COVID-19 is now a fact of life in most of the world. This lack of direction – in contrast to the resoluteness with which both Xi and Li attempt to project in their respective interests – is now fanning the flames of discontent from below.

Inflammable material

Even before the instability set off by the new round of outbreaks, China was already a country filled with uncertainty and discontent. For one, the potential economic bombshell over Evergrande’s crisis remains unsolved, while the housing market seems to be inching closer to the edge, with another developer, Sunac, being wracked by a debt crisis.

Various social incidents such as the imprisoned mother of eight in Xuzhou, or most recently the outrage over violence against women in Tangshan and the police’s downplaying of the incident, have also sparked immediate widespread outrage among the public, mostly on the internet. Many cases of outrage over grotesque injustices are becoming more frequent in recent times. All these underpin a growing sentiment amongst the masses: that there is something deeply wrong with the current society.

Under these conditions, the added pressure and uncertainty over the lockdown measures are a whole bundle of straws loaded onto the camel’s back. In some cases, this has actually resulted in physical demonstrations, like the small scale riots around Shanghai, or when the students of Peking University and Tianjin University amassed spontaneously to protest the brutal lockdowns. The Tianjin University students were even heard chanting “Down with bureaucratism!”

All of the above are but expressions of the deep necessity for change in China. More precisely, the need to do away with capitalism through a genuine socialist revolution. The CCP regime’s pipedream of “market socialism” is turning into a nightmare for the masses. No amount of economic stimulus or bureaucratic measures can do away with the organic contradictions of the capitalist system. Sooner or later, the masses will take their grievances from their keyboards to the streets, and they will need the ideas of genuine revolutionary Marxism to win against their ruling class oppressors.