A recurring lesson in history is that no ruling class ever gives up its wealth, power and privileges without a fight. Those who threaten the existing order face the most savage repression. The state, which represents the interests of the ruling class, will use every means at its disposal to destroy those who challenge this power—from infiltrating and sowing division among mass movements to imprisoning and killing their leaders.

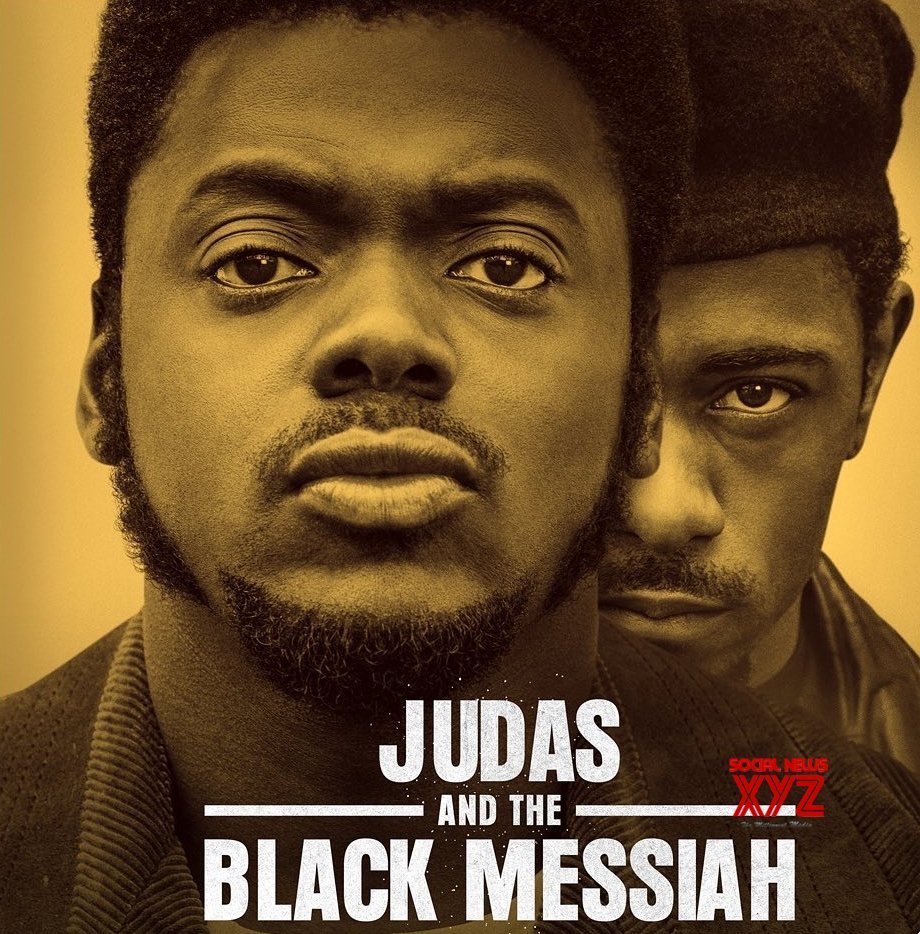

A new film directed by Shaka King, Judas and the Black Messiah, dramatizes one such episode from U.S. history: the attempt of the FBI to destroy the Black Panther Party (BPP) and one of its greatest leaders, Fred Hampton. The film chronicles the betrayal of Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), deputy chairman of the BPP Illinois chapter, by William O’Neal (LaKeith Stanfield), a petty criminal and FBI informant who infiltrated the party.

Note: This review contains details of Fred Hampton’s life and the history of the Black Panthers that may constitute “spoilers”.

The release of a film that portrays Hampton and the BPP in a more favourable light is certainly welcome. Depictions of the Panthers in popular media have tended to echo the vicious smears put forward by the FBI and its arch-reactionary director J. Edgar Hoover, who attacked the Panthers as dangerous “extremists” sowing “terror” and “preaching [a] gospel of hate and violence”. In Judas and the Black Messiah, Hampton—portrayed superbly by Daniel Kaluuya—is a charismatic popular leader who unites activists across racial lines and connects the struggle against racism with the fight against capitalism.

The fights against racism and capitalism are indeed part of the same struggle. As Malcolm X, a major inspiration for the founders of the BPP, observed, “You can’t have capitalism without racism.” While the BPP held an eclectic and sometimes contradictory range of ideologies, it clearly understood the connection between capitalism and racism and that only revolutionary socialism could end these evils. The potential threat this posed to the ruling class made the Black Panthers Public Enemy No. 1 in the eyes of the U.S. state security apparatus.

Though set in late 1960s Chicago, the themes of Judas and the Black Messiah could not be more timely. Its release comes several months after the Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd, which exploded into the largest mass movement in United States history and fuelled international protests against racism and police brutality. That momentous uprising also coincided with the global economic collapse following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ongoing crisis has thrown into sharp relief the inability of capitalism to provide for the basic needs of working people such as jobs, health care, education and housing—demands that were central to the program of the Black Panthers.

The International Marxist Tendency (IMT) has previously written on the history of the Black Panther Party and provided a detailed analysis of its program, which is beyond the scope of this review. We highly recommend these articles to readers who wish to learn more about the Panthers—their achievements, their often serious errors and limitations, and the lessons revolutionaries can draw from these experiences today. But how are the Panthers portrayed in King’s film?

Need for historical context

In Judas and the Black Messiah, we see the BPP organizing community medical clinics and their Free Breakfast for Children program. We see Hampton serving as an instructor at political education classes for party members. We see him giving fiery speeches to supporters and forging alliances with Chicago gangs and groups such as the Young Patriots, a leftist organization of white Southerners, and the Young Lords, a radical Puerto Rican and Latino activist organization. This building of an alliance of radical activists across racial lines—including a pertinent exchange about the Confederate flag—is a refreshing antidote to the “stay-in-your-lane” identity politics so prevalent today.

On a more personal level, the film also depicts a touching romance between Hampton and fellow party member Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback), a poet who was eight months pregnant with Hampton’s son at the time he was assassinated on Dec. 3, 1969. Throughout the film, King highlights the important role of women in the Black Panthers. Women represented 60 per cent of the party’s membership in 1969, according to an internal BPP survey.

However, while including verbatim many of Hampton’s speeches, Judas and the Black Messiah arguably gives short shrift to the Panthers’ politics—ideas deeply threatening to the capitalist power structure both then and now. It also conveys little of the wider historical context behind the rise of the BPP.

The meteoric rise of the Panthers was part of a wider wave of revolutionary movements that swept the world in the 1960s. The BPP itself was founded in the wake of the U.S. civil rights movement—in part as a reaction to its ebb—by young Black radicals who saw persistent racial and economic disparities as directly linked to class oppression under capitalism. The party’s peak years coincided with radical student movements and campus occupations, opposition to the war in Vietnam, struggles for women’s rights and gay rights, and revolutions in countries from France to Czechoslovakia to Pakistan.

Portrayal of state repression

Revolutionary movements tend to meet with counter-revolutionary backlash, and the BPP was no exception. Judas and the Black Messiah shows the campaign of harassment, psychological warfare and state repression waged against the Panthers as part of the FBI’s COINTELPRO campaign targeting “subversive” groups and individuals. The film highlights the pernicious role of O’Neal, who is arrested early on for stealing a car. To avoid a lengthy prison sentence, O’Neal agrees to an offer by FBI agent Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons) to join the Panthers in Chicago as an informant.

FBI agents in the film produce fake flyers to smear the party’s reputation and to sabotage alliances with other community groups. Chicago police murder party members. O’Neal shows Hampton a trunk full of explosives while wearing a wiretap and tries to encourage him to bomb city hall. Hampton is arrested and imprisoned for months on trumped-up charges of allegedly stealing $71 worth of ice cream.

Finally, there is the assassination of Hampton himself by FBI and Chicago police in a predawn raid on his apartment. The film recreates in chilling detail the real-life state murder of Hampton, one of the most notorious acts of counter-revolutionary violence in U.S. history. Drugged with a sedative by O’Neal, Hampton is shot to death while sleeping beside his pregnant girlfriend. The depiction of police breaking into an apartment and killing a Black person asleep in their own bed may remind some viewers of Breonna Taylor, the Kentucky woman murdered under similar circumstances in March 2020. Taylor’s death further fueled last year’s mass protests against racism and killer police. The parallels between Hampton’s assassination and Taylor’s murder underscore the persistence of racist state violence under capitalism.

Hoover (Martin Sheen) is correctly portrayed in the film as a loathsome individual: a rabid racist and fanatical anti-communist who considers the Panthers “the single greatest threat to our national security.” In explaining the need to confront the Panthers, he cites Mitchell’s eight-month old daughter and asks him, “What will you do when she brings home a Negro?” Such a possibility, Hoover says, represents the threat to “our way of life” that the Panthers supposedly pose. While this kind of vile racism was undoubtedly a key part of the FBI’s opposition to the Panthers, their campaign to destroy the party was prompted in the last analysis by the state’s role as a defender of class society, in this case capitalism.

For his part, Mitchell is portrayed as something of a “liberal” in the FBI. The agent gives lip service to progressive values while doing everything in his power to destroy any threats to the capitalist state, which relies on racism as one of its most effective means to keep the working class divided. “I’m all for civil rights,” Mitchell claims to O’Neal. “But you can’t cheat your way to equality, and you certainly can’t shoot your way to it.” His words convey the hypocrisy of state institutions that claim to abhor violence while murdering anyone who opposes them. Mitchell also paints a laughable false equivalence between the Black Panthers and the Ku Klux Klan, similar to how defenders of the status quo today draw a false equivalence between anti-racist protesters and far-right racists.

It is the film’s focus on O’Neal that exemplifies some of its biggest weaknesses. As refreshing as it is to see a Hollywood film portraying the Black Panthers in a positive light, we must acknowledge that this film is predominantly told from the viewpoint of an FBI informant. It is no coincidence that it is the “Judas” O’Neal, not the “Black Messiah” Hampton, who occupies first place in the film’s title.

One may argue that the dual focus on O’Neal and Hampton is a valid artistic choice, yet there is reason to suspect that this choice was in part a way of softening the film’s sympathetic presentation of the BPP. Judas and the Black Messiah is, after all, something of a rarity as a major Hollywood film that portrays a revolutionary socialist and member of the Black Panther Party as a central protagonist (one of its few predecessors, the semi-fictionalized 1995 Mario Van Peebles film Panther, also revolved around an informant within the party). Compare this to the countless films, books and TV shows that have depicted FBI agents as the protagonists. Even Mississippi Burning, a 1988 film based on the murder of three civil rights activists by the Ku Klux Klan, featured two white FBI agents as the heroes.

King’s film also depicts O’Neal in a more favourable light than his real-life counterpart. Stanfield portrays O’Neal as conflicted in his duplicity and somewhat sympathetic to the Panthers’ rhetoric; despite serving as an informant until 1983, he considers himself a part of the movement right up to his death by suicide in 1990. In reality, O’Neal did not consider his acts a “betrayal” at all and bluntly stated, “I had no allegiance to the Panthers.”

Capitalism behind the scenes

The production of Judas and the Black Messiah in many ways illustrates how the capitalists who provide the funding for film production and distribution are able to influence the content of art that reaches a mass audience.

In a Hollywood Reporter article on the making of the film, King described his difficulties in getting the picture made—despite its historic and relevant subject matter, acclaimed cast, and industry clout of producer Ryan Coogler, who had directed the superhero blockbuster Black Panther. Even having half the budget covered by Coogler and Charles D. King (no relation)—who together with Shaka King are founding members of Blackout for Human Rights, an organization of artists seeking to raise awareness of police brutality—was not enough to convince studios to greenlight the film:

Shaka King expected a bidding war for Judas, considering its pedigree. It never came. “I was surprised, yes. The movie sold itself, in my opinion. You could pitch it as, ‘from the director of Black Panther comes the story of an actual Black Panther,’ ” he says. “You’ve got LaKeith and Daniel, who are two of the best actors of their generation and bona fide movie stars. You’ve got Charles D. King putting up half the budget. So it’s not like the studio has to fully finance it.”

In pitching their story, screenwriters Keith and Kenny Lucas said they “wanted to make The Departed inside the world of COINTELPRO,” the director recalls. Fellow screenwriter Will Berson said that Shaka King described the project to him as “a biopic of Fred Hampton inside a classic 1970s thriller.” The latter two, The Hollywood Reporter details, “wrote a script based on the Lucas brothers’ provocative idea of focusing on both O’Neal and Hampton.” It was evidently this pitch that met with the approval of Warner Bros., which agreed to distribute the picture. One imagines that a capitalist film studio might have been more reluctant to finance a film that placed a greater focus on the revolutionary politics of the BPP and the mass movements of students and workers convulsing the world at the time.

Despite its limitations, Judas and the Black Messiah is a riveting and well-made film with stellar performances. For the uninitiated, it is a fine introduction to Fred Hampton and the BPP that will hopefully encourage viewers to learn more about the history of the party and the ideas of revolutionary Marxism.

In one of the movie’s key scenes, Hoover plays footage of the Black Panthers to explain to an army of FBI agents why he considers the party to be the greatest threat to “national security.” The clip ends with Kaluuya as Hampton reciting one of the chairman’s most famous speeches: “We don’t think you fight fire with fire best; we think you fight fire with water best. We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we’re going to fight it with socialism.”

Hampton’s words remain just as vital today—and just as threatening to the ruling class. If you’d like to put them into practice and help build the forces of Marxism, we encourage you to get involved with Fightback and the IMT.