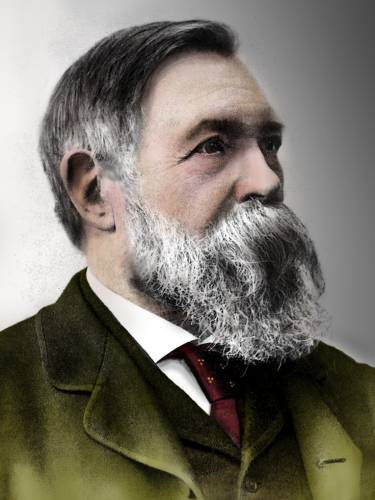

28 November marks the 200th birthday of Friedrich Engels. Rob Sewell commemorates this bicentenary by looking at the vital contribution that Engels made to developing the ideas of Marxism, for which we owe him an enormous debt of gratitude.

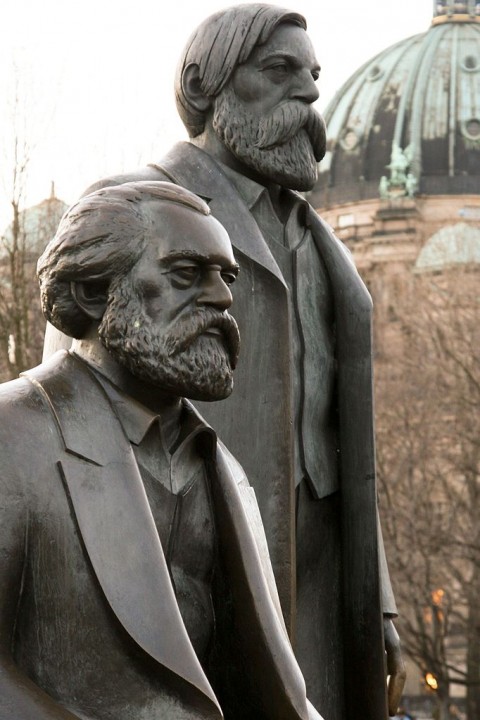

In celebrating the 200th birthday of Friedrich Engels, the co-founder of the ideas of scientific socialism, along with Karl Marx, we should take this opportunity to touch upon the life of this great man and the marvellous contributions he made.

Although Marxism bears the name of Marx, we should never forget the vital contribution made by Engels, and the organic link between the lives of these two men. Without a doubt, Engels possessed an encyclopedic mind that encompassed a knowledge of such diverse fields as philosophy, economics, history, physics, philology and military science. His knowledge of the latter earned him the nickname ‘The General’.

All too often, Engels is seen as playing a subsidiary role to Marx. While Marx was a titan in every possible way, Engels was key in this relationship too. Always extremely modest, Engels would defer to Marx. But when we read the voluminous correspondence between the two men, Engels’ own outstanding contribution is unmissable. Together with Marx he was a political giant.

Early life

A number of biographies of Engels’ life have been written, some good and some bad. One of the latest is that of the pretentious Tristram Hunt, entitled The Frock-Coated Communist, which stands out as a particularly bad account of Engels’ life.

But what more can we expect from such people? Bourgeois historians have their axes to grind, especially when writing about Marx and Engels. The petty Tristram Hunt is no exception. We have nothing to learn from the gossip of such pseudo-intellectuals.

Born into a family of Barmen textile manufacturers in the Rhineland, the young Engels broke from his class background and put himself at the standpoint of the working class. From then on, he dedicated himself to the overthrow of capitalism and the emancipation of the working class. Along with Marx, who also came from a bourgeois background, he became one of the greatest leaders of the working class.

In his early twenties, Engels ‘openly aligned’ with revolutionary Chartism and wrote his famous Condition of the Working Class in England. He made direct contact with the workers’ movement in England and it was here that Engels became a confirmed Communist.

In his early writings, although not fully rounded out, he had, as Marx wrote, “already formulated certain general principles of scientific socialism”.

Marx

His meeting and friendship with Marx began in August 1844. This led to a lifelong political and theoretical collaboration, which was to transform the world. As Engels later recalled:

“When, in the spring of 1845, we met again in Brussels, Marx had already fully developed his materialist theory of history in its main features…and we now applied ourselves to the detailed elaboration of the newly-won outlook in the most varied directions.”

This collaboration was to bear fruit in a series of theoretical works, such as the German Ideology, culminating a few years later in the Communist Manifesto. In the process, the two men battled with others who held all sorts of confused ideas and notions.

“It is disgraceful that one should still have to pit oneself against such nonsense,” wrote Engels. “I shall not let the fellows go until I have driven Grün [a utopian socialist] from the field and have swept the cobwebs from their brains.”

The close bond and relationship between the two men became ever closer. In the words of Lenin:

“Old legends contain many moving instances of friendship. The European proletariat may say that its science was created by two scholars and fighters, whose relationship to each other surpasses the most moving stories of the ancients about human friendship.”

Trotsky, who studied every aspect of Engels’ life and contribution, also provided a fitting assessment of Engels:

“Engels is undoubtedly one of the finest, best integrated and noblest personalities in the gallery of great men. To recreate his image would be a gratifying task. It is also a historical duty…

“How well they [Marx and Engels] complement one another! Or rather, how consciously Engels endeavours to complement Marx; all his life he uses himself up in this task. He regards it as his mission and finds in it his gratification. And this without a shadow of self-sacrifice – always himself, always full of life, always superior to his environment and his age, with immense intellectual interests, with a true fire of genius always blazing in the forge of thought.

“Against the background of their everyday lives, Engels gains tremendously in stature by comparison with Marx – though of course Marx’s stature is not in the least diminished by this. I remember that after reading the Marx-Engels correspondence on my military train, I spoke to Lenin of my admiration for the figure of Engels. My point was just this, that when viewed in his relationship with the titan Marx, faithful Fred gains – rather than diminishes – in stature.

“Lenin expressed his approval of this idea with alacrity, even with delight. He loved Engels very deeply, and particularly for his wholeness of character and all-round humanity. I remember how we examined with some excitement a portrait of Engels as a young man, discovering in it the traits which became so prominent in his later life.

“When you have had enough of the prose of the Blums, the Cachins, and the Thorezes [the reformists and Stalinists], when you have swallowed your fill of the microbes of pettiness and insolence, obsequiousness and ignorance, there is no better way of clearing your lungs than by reading the correspondence of Marx and Engels, both to each another and to other people. In their epigrammatic allusions and characterisations, sometimes paradoxical, but always well thought out and to the point, there is so much instruction, so much mental freshness and mountain air! They always lived on the heights.”

Trotsky continued:

“Engels’ prognoses are always optimistic. Not infrequently they run ahead of the actual course of events. But it is possible in general to make historical predictions which – to use a French expression – would not burn some of the intermediate stages?

“In the last analysis Engels is always right. What he says in his letters to Mme. Wischnewetsky about the development of England and the United States was fully confirmed only in the post-war epoch, forty or fifty years later. But it certainly was confirmed! Who among the great bourgeois statesmen had even an inkling of the present situation of Anglo-Saxon powers? The Lloyd Georges, the Baldwins, the Roosevelts, not to mention the MacDonalds, seem even today (in fact, today even more than yesterday) like blind puppies alongside the far-sighted old Engels. And how thick-headed all these Keyneses are to proclaim that the Marxist prognoses have been refuted!”

(Trotsky, Diary in Exile, pp.27-29)

Materialism

As young men both Marx and Engels were followers of the great German philosopher Hegel. His teachings were without a doubt revolutionary. Hegel’s dialectical method became the cornerstone of their outlook, but they purged it of idealism and placed it on its feet. Through Feuerbach, they became materialists. Materialist philosophy explains that matter is primary, and ideas are a reflection of the material world.

They were the first to explain that socialism was not the invention of dreamers, but rooted in the development of the productive forces and the class struggle. Socialism finally became a science. “Without German philosophy,” explained Engels, “scientific socialism would never have come into being.”

Engels in particular contributed to the philosophy of Marxism in his later works, namely Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Anti-Dühring and the Dialectics of Nature.

Engels, along with Marx, understood the importance of the working class. In his Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1845, he explains that the proletariat is not only a suffering class, but a class that fights for its own emancipation. His joint work with Marx, the Communist Manifesto, brings these ideas to fruition.

Dialectics

With the failure of the 1848 revolution, Marx and Engels found themselves in England – Marx in London and Engels in Manchester. In Manchester, Engels went to work for his father’s firm, the “accursed trade”, so as to provide material assistance to Marx.

Correspondence between the two men took place almost on a daily basis. Through their letters, they exchanged their ideas, thoughts, and discoveries in all their richness.

In 1870, Engels finally moved to London so that he and Marx could directly participate in their joint intellectual collaboration, as well as take an active part in the work of the First International. This work was of tremendous significance in binding the advanced workers of all countries together in an organisation.

By then Marx had finished writing the first volume of Capital and was elaborating material for two further volumes. When he finished the first volume in August 1867 he wrote to Engels:

“So, this volume is finished. I owe it to YOU alone that it was possible! Without your self-sacrifice for me I could not possibly have managed the immense labour demanded…”

While Marx spent most of his time on Capital, Engels engaged in other polemics, which allowed him to outline the basic concepts of Marxism. This included Anti-Dühring, which delved into philosophy, natural sciences and the social sciences. He also wrote the Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State, in which he applied the materialist conception to the remote past of human history. And he penned Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of German Classical Philosophy.

“Marx and I,” wrote Engels, “were pretty well the only people to rescue conscious dialectics [from the destruction of idealism, including Hegelianism] and apply it in the materialist conception of Nature…Nature is the proof of dialectics, and it must be said for modern natural science that it has furnished extremely rich and daily increasing materials for this test, and has thus proved that in the last analysis Nature’s process is dialectical and not metaphysical.”

“The great basic thought,” explained Engels, “that the world is not to be comprehended as a complex of ready-made things, but as a complex of processes, in which the things apparently stable no less than their mind images in our heads, the concepts, go through an uninterrupted change of coming into being and passing away…this great fundamental thought has, especially since the time of Hegel, so thoroughly permeated ordinary consciousness that in this generality it is now scarcely ever contradicted. But to acknowledge this fundamental thought in words and to apply it in reality in detail to each domain of investigation are two different things…

“For dialectical philosophy nothing is final, absolute, sacred. It reveals the transitory character of everything and in everything; nothing can endure before it except the uninterrupted process of becoming and of passing away, of endless ascendency from lower to the higher. And dialectical philosophy itself is nothing more than the mere reflection of this process in the thinking brain.”

Therefore, according to Marx and Engels, dialectics is “the science of the general laws of motion, both of the external world and of human thought.”

Capital

Marx and Engels’ inspiration grew as the movement grew. After Marx’s death, Engels continued alone as the counsellor and leader of the European socialist movement, which had become a mass force. His advice was eagerly sought after, and he drew on his vast knowledge and experience in his old age.

Like Marx, Engels knew many foreign languages and conducted a massive correspondence on a host of questions. Incredibly, this covers 13 volumes of the Collected Works, amounting to 3,957 letters. These reveal the fascinating close bond between them and their joint work.

Marx died before he could put the final touches to his vast work on political economy. Using the drafts left by Marx, Engels put his own research aside and took on the colossal task of completing Marx’s work, editing and publishing volumes two and three of Capital. Only he could decipher Marx’s unintelligible handwriting.

As he wrote to Lavrov: “I am all the more worried because I am the only one alive who can decipher this handwriting and these abbreviations of words and sentences.”

To accomplish this task he dictated every day from 10am to 5pm to the job. He also had to edit the work and make necessary additions. Thus he endeavoured to complete the work “exclusively in the spirit of the author”.

In relation to volume two and three of Capital, Lenin wrote approvingly: “These two volumes of Capital are the work of two men: Marx and Engels.”

As Trotsky explained:

“Engels was not only a man of genius but also the soul of conscientiousness. In literary work as well as in practical affairs he could not bear sloppiness, inaccuracy, and inexactitude. He checked every comma (in the literal sense of the term) of Marx’s posthumous work, and carried on a correspondence on the subject of secondary orthographic errors.”

Leader

Engels regarded the writing of The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, written a year after Marx’s death, as a “fulfilment” of “a bequest” by Marx. This work can be regarded as one of the fundamental works of modern socialism.

After Marx’s death, Engels became the direct and unchallenged leader of world socialism until his death twelve years later.

In June 1884, when Berstein and Kautsky complained to him about the pressures of the different “erudite” philistines in the party, Engels replied, “the main thing is to concede nothing and, in addition, to remain absolutely calm.”

Throughout this time, Engels took up the defence of scientific socialism, answering the distortions and misconceptions.

“According to the materialist conception of history,” he wrote to Joseph Bloch in September 1890, “the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. More than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted.”

“Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure – political forms of the class struggle and its results, to wit: constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas – also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form.”

Modesty

Engels was indignant against those newly-baked ‘Marxists’, who thought they understood Marxism and could apply it with impunity, without mastering its principles.

“In Marx’s lifetime,” wrote Engels to Johann Philipp Becker, “I have done what I was cut out to do – I played second fiddle – and I think that I did it fairly well. I was so glad to have so splendid a first violin as Marx.

“And now that I am unexpectedly called upon to replace Marx in theoretical matters and play first fiddle, I cannot do so without making slips of which nobody is more keenly aware than I.

“But it is not until stormier times come that we shall really appreciate what we have lost in Marx. None of us has that breadth of vision with which he, whenever it was necessary to act quickly, did the right thing and tackled the decisive issue. True, in peaceful times it sometimes happened that events proved me right, but at revolutionary moments his judgment was all but unassailable.”

With this modesty Engels displayed his love for Marx and his reverence towards his memory. He wrote to Franz Mehring:

“If one has been fortunate enough to spend forty years collaborating with a man like Marx, one tends, during one’s lifetime, to receive less recognition than one feels is due to one; when the greater man dies, however, the lesser may easily come to be overrated – and that is exactly what seems to have happened in my case; all this will eventually be put right by history, and by then one will be safely out of the way and know nothing at all about it.” (14th July 1893)

Opportunism

Engels played a colossal role in helping to guide the forces of the Second International. He attended the Third Congress of the International in Zurich. In the closing session, he addressed the delegates first in English, then in French, then in German.

He studied at the newspapers of the sections and the specific conditions in each country. He wrote letters and received numerous visitors to his home at Regent’s Park Road. He could converse freely in English, French, Italian, and could read Spanish and almost all Slavic and Scandanavian languages.

In his last years, he was not afraid to challenge the opportunist ideas that had surfaced in the powerful German and French sections. He dropped a bombshell on the opportunists with his new introduction to Marx’s The Civil War in France. In this, he stressed that the state “is nothing more but a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and indeed in the democratic republic no less than in the monarchy.”

By way of an example he pointed to the United States, where, he wrote:

“Two great gangs of political speculators, who alternately take possession of the state power and exploit it by the most corrupt means and for the most corrupt ends – and the nation is powerless against these two great cartels of politicians, who are ostensibly its servants, but in reality dominate and plunder it.”

He concluded his introduction to Marx’s pamphlet with the following words addressed to the opportunists in the German Social Democracy:

“Of late, the Social Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesale terror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.”

He followed this up with an attack on reformism and “parliamentary cretinism” in the party. The bureaucrats in the leadership of the Social Democracy Party omitted several passages to water down his criticism and make him out to be a defender of pacifism.

What Engels was rejecting was not revolutionary action in general, but rather the actions of untimely flurries of a small minority, and forms of street fighting that did not correspond to new technological conditions. When he found out what had been done in his name, he was furious. These opportunist tendencies later gave rise to Bernsteinism and revisionism, which eventually led to the betrayal of August 1914.

Communism

Despite his advancing years, Engels was young at heart and certainly had a sense of humour, stating he was “still nimble on his pins”. In another letter he wrote:

“That is my position: 74 years the which I am beginning to feel, and work enough for two men of 40. Yes, if I could divide myself into F.E. of 40 and the F.E. of 34, which would just be 74, then we should soon be all right. But as it is, all I can do is to work on with what is before me and get through it as far and as well as I can.” (Letter from Engels to Laura Lafargue, 17 December 1894)

In one of his last letters to Lavrov, he states:

“I cannot complain, but I am beginning to realise that 74 is not 47. However, events should help us to maintain our vital forces, the whole of Europe is warming up, crises are brewing everywhere, particularly in Russia. The situation cannot last much longer over there. So much the better.” (18/12/94)

In a letter to Bebel he concludes: “And while passing a resolution on these points mind you drink a bottle of good wine; do this in memory of me.” This was typical of Engels, who lived life to the full.

Engels died on 5 August 1895 – a revolutionary communist to the very core. His ashes were cast into the sea off Beachy Head in Eastbourne. Without doubt his revolutionary spirit lives on in the Marxist tendency, which defends his legacy, and the struggle for world socialism.