With the 50th anniversary of the October Crisis of 1970, debates about the Front de Libération du Quebec (FLQ) have resurfaced. Some denounce the “Felquistes” as vulgar “terrorists”. Others celebrate them as a model to be followed. Still others recognize the problems denounced by the FLQ, but feel that they should have used “democratic” means to achieve their ends.

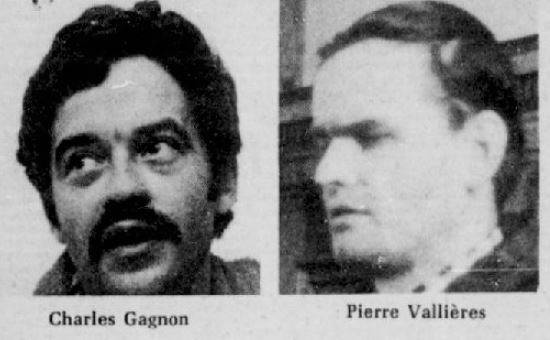

For Marxists, there is no doubt that the FLQ revolutionaries showed courage and tenacity rarely seen in the history of Quebec. But we must admit the failure of their methods. Although the worst manifestations of the oppression of the Quebecois have been lessened, we still do not live in a “free society forever purged of its clique of voracious sharks,” in the words of the FLQ manifesto. As Charles Gagnon once said, “There are still poor people, even if they can buy their rags in French.”

The same reactionary federal state that the Felquistes fought against is still in place, and the “big bosses” of both the Anglophone and Francophone bourgeoisie continue to exploit the workers. The struggle undertaken by the revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s is far from over. It is for this reason that it is important not to merely glorify or condemn the FLQ, but to soberly study its errors and weaknesses. More than ever today, we need a revolution, and the history of the FLQ and its lessons can help us to understand the way forward in this struggle.

La Grande Noirceur

To understand the FLQ, one must understand the historical context in which it emerged. This context is the Quiet Revolution in Quebec.

Following the Second World War, the advanced capitalist countries experienced a period of unprecedented economic boom. Quebec’s economy was also developing and modernizing. But its political structure remained backward. This period has been called La Grande Noirceur (“The Great Darkness”), which lasted from the election of Maurice Duplessis in 1944 until his death in 1959. Duplessis ruled Quebec as a despot (he was nicknamed Le Chef or “The Boss”) on behalf of the American and Anglo-Canadian imperialists.

The imperialists’ domination of Quebec, the basis of the national liberation movement, is explained by the historical weakness of the Quebec bourgeoisie. The British conquest had hindered the process of development of a Francophone bourgeoisie in Quebec. Quebec then became the playground of the Anglo bourgeoisie. As a result, the French-Canadian bourgeoisie was weak and excluded from heavy industry and finance, concentrating its activities on the traditional rural economy and service industries on behalf of the large English-speaking corporations. It controlled less than 20 percent of the Quebec economy.

Le Chef, at the head of his province, assured his American and English-Canadian masters access to natural resources and cheap labour. At that time, Quebec was like a big “sweatshop,” with Francophone workers and Anglophone bosses and foremen. In 1961, the average salary of unilingual Francophone men was 52 percent of that of Anglophone men, whether bilingual or unilingual. While Quebec represented 27 percent of the population of Canada, it accounted for 40 percent of the unemployed in the country.

To ensure the docility of these exploited workers, the Quebec despot promoted a conservative and religious nationalism, with the complicity of the Catholic Church. When this did not work, the police were sent to repress the seditious elements. The infamous Padlock Law was also introduced in 1937, which was used to close places used by communists and prohibited publications “tending to propagate communism or bolshevism”.

But the Duplessis regime was unable to keep the lid on the cauldron. The post-war boom led to rapid industrialization in Quebec, and corresponding urbanization. In 1960, 70 percent of the population lived in cities. The working class developed, as did its activity. In the early 1930s, the unionization rate in Quebec was between eight and 10 percent, but it rose to 28.3 percent in 1959. The 1950s were marked by vigorous strikes that represented an awakening of the Quebec labor movement, notably the Asbestos strike of 1949 and those of Louiseville and Dupuis Frères in 1952 and the Murdochville strike of 1957. The unions underwent profound transformations, with the deconfessionalization of the Confederation of Catholic Workers of Canada, the forerunner of the CSN, and the founding of the Fédération des Travailleurs du Québec (FTQ).

Encouraged by the strength of the workers’ movement, the Francophone petty bourgeoisie also raised its head. Accustomed to serving its imperialist masters, it began to dream of being “Maîtres chez nous” (“master in our own home”). The death of Duplessis in 1959 gave the final push to this process.

The Quiet Revolution

The Liberal Party of Jean Lesage was elected in 1960 on a program of reforms, reflecting the aspirations of the Francophone petty bourgeoisie. Thus began the Quiet Revolution. The Quebec state was undergoing rapid modernization. The deconfessionalization of the education system dealt a heavy blow to the Church, as did the state takeover of the healthcare system, which had until then been managed by the Church. Unfortunately, the labour movement had failed to create a worker’s party in the previous period, and the union leadership of the FTQ and CSN supported the PLQ in the 1962 election. In return, and following militant struggles, workers were given some concessions: a new labour law gave more rights to unions and state employees were given the right to organize and strike.

The Quiet Revolution was also an opportunity for the weak Francophone petty bourgeoisie and bourgeoisie to consolidate. While the Francophone bourgeoisie was too weak to compete with Canadian-American imperialism, the state represented a lever capable of supporting the development of a strong Francophone bourgeoisie taking control of the Quebec economy. This is what the slogan “Maîtres chez nous” used by the Liberals in the 1962 election really meant. The Liberal Party manifesto during this campaign stated that “the era of economic colonialism is over in Quebec”.

The most famous example of this economic nationalism is the nationalization of hydro-electricity, led by the Minister of Natural Resources, René Lévesque, and the creation of Hydro-Québec. Several other state corporations were created to take natural resources out of the hands of the imperialists, such as SOQUEM (mining exploration), REXFOR (forestry), Sidbec (metallurgy), and SOQUIP (oil).

In addition, the Liberal Party strengthened the Francophone bourgeoisie by giving it access to capital. Indeed, the weakness of the Francophone bourgeoisie was partly explained by its dependence on foreign capital. Recognizing this problem, the largest Francophone bourgeois families had already come together in 1958 to create Corpex, the first business bank under Francophone control and at the service of Francophone businessmen. In the same spirit, the Lesage government set up two financial institutions, the Société générale de financement (1962) and the Caisse de dépôt et de placement du Québec (1965), which gave access to capital to developing Francophone businessmen. The Quiet Revolution thus saw the Francophone bourgeoisie carve out a place for itself in the economy.

Lastly, the Quiet Revolution gave rise to an intellectual ferment and a questioning of the established order. The floodgates had been opened. The Quiet Revolution was not entirely channelled by the Liberal Party. In spite of the reforms, many workers remembered that it was a corrupt bourgeois party. For some, the reforms didn’t go fast enough or far enough. The condition of the working class remained miserable. The idea of national liberation through independence was gaining popularity.

On the left and within the labour movement, inspired by the colonial revolutions and socialist ideas, groups promoting independence, socialism, or both, appeared. This began in the early 1960s, and is the backdrop for the birth of the FLQ.

Notably, the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale (RIN), a centre-left independence group, was founded in September 1960, and became an electoral party in 1963. Marcel Chaput, one of its leaders, published a small book entitled Pourquoi je suis séparatiste (“Why I am a separatist”), which caused a sensation.

The Action socialiste pour l’indépendance du Québec (ASIQ) was founded in August 1960. It remained a marginal group, but influenced the future ideology of the FLQ. For example, one of its main theoreticians, Raoul Roy, wrote that “the French Canadians form a colonized and almost entirely proletarianized people, occupied by a large colonialist bourgeoisie of foreign language and culture”. His 1962 article “The Effectiveness of Violence” represents perhaps the beginnings of the shift towards individual terrorism among the most radical wing of the indépendantistes: “Unless Quebec indépendantistes are content with a small percentage of the vote election after election… it will be necessary to consider other forms of action that are more likely to shake and break the apparatus of colonialist occupation in Quebec… We have reached the point where we have no alternative to violence as a means of making ourselves heard.”

The founding of the FLQ

The autumn of 1962 was marked by harshly repressed demonstrations. Some members of the RIN began to turn to more “radical” methods and secretly formed the Comité de libération nationale (CLN) in October 1962 and the Resistance Network in November 1962. The CLN aimed to begin the construction of an organization that was both political and “military”, i.e. capable of armed action. The Network met to carry out “direct actions” against “colonial symbols,” i.e. vandalism. But one wing wanted to go further. It set fire to CN Rail buildings and trucks in Montreal, and threw a Molotov cocktail through a window of the English-language radio station CKGM. The CLN and the Network were quickly disbanded, but their most radical wing was reconstituted as the Front de libération du Québec.

The FLQ was established in February 1963 by Raymond Villeneuve, Gabriel Hudon and George Schoeters. They formed the nucleus of what would later become known as the “FLQ-63”, which carried out the first wave of attacks. On the night of March 7-8, they attacked three military barracks with incendiary bombs. The FLQ issued its first communiqué: “The independence of Quebec is only possible through social revolution… Students, workers, peasants, form your underground groups against Anglo-American colonialism. Independence or death!”

The term “social revolution” used here characterizes quite well the ambiguity of the FLQ’s ideology. Even Pierre Bourgault, leader of the RIN—who is, after all, quite “moderate” by his own admission—had affirmed at the RIN’s founding congress as an electoral party a few days earlier, on March 4, “Independence must go hand in hand with social revolution.” If the FLQ generally said it was fighting for the workers, its project of revolution remained unclear. The FLQ defined itself more by its methods centered on armed struggle than by its ideology, oscillating between nationalism and a rather vague socialism, with touches of Marxism here and there.

This ideological confusion can be explained in part by the structure of the organization. Far from being a democratic organization with clear structures and elected governing bodies, the FLQ rather took the form of a “movement” or banner. Over the course of its existence, different networks, cells, organizations, etc. laid claim to the FLQ banner. The links between these groups varied in strength, which formed and broke up spontaneously as the police caught some of them. Between the different networks, the “socialist” aspect of the project varied in emphasis.

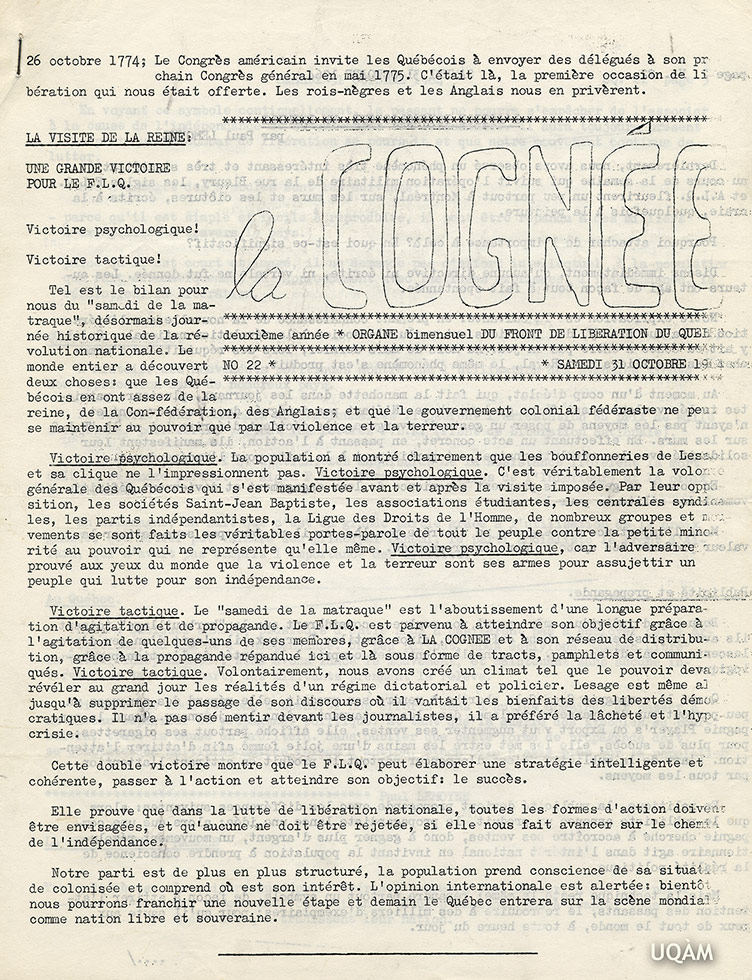

For example, the network of La Cognée, the movement’s newspaper, saw itself as the FLQ’s “central committee” (its real authority remains to be proven). La Cognée systematically and voluntarily avoided using the term “socialism” for “tactical” reasons. But the famous Vallières-Gagnon network was more clearly Marxist and spoke openly about socialism, and in 1966 replaced La Cognée as the ideologically dominant network.

Independence or socialism?

However, there is a deeper explanation of this confusion. The 1960s were marked by a great confusion on the left that affected almost all groups and parties. If socialism was popular in large parts of the Québécois labour movement, the national question muddied the waters. How were national liberation and the liberation of the workers’ to be reconciled? The RIN, although it talked about “social revolution”, focused first and foremost on the issue of independence. This eventually led the party to simply dissolve itself and suggest that its activists join the nascent Partie Québécois (PQ). The popular pro-independence, socialist magazine Parti pris defended a “stagist” position in its 1964 Manifesto—Quebec independence in alliance with the Quebec bourgeoisie first, and socialism later.

The problem is that almost no one put forward a clear class position. The role of the revolutionary activists of the time was to put forward an openly socialist program aimed at uniting the Quebec working class in a mass socialist party of the working class. This would have pulled the rug from under the feet of the Liberals, who claimed to want to liberate Quebec, and later of the PQ, which wanted to unite all classes in the province in the struggle for sovereignty. It should have been made clear that the Liberal half-reforms and the PQ project were a dead end that would not liberate Quebec workers.

James Connolly, the Irish revolutionary, explained, “If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organization of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs.” In a similar fashion, in Quebec, national liberation could only be achieved through a socialist revolution against both the Anglophone imperialists and the francophone bourgeoisie. Independence led by a party of businessmen and lawyers would solve none of the problems of Québécois workers.

What needed to be argued was that entrusting the national liberation struggle to one of these parties was a mistake, and that a socialist program of nationalization of the great levers of the economy, under the democratic control of the working class, was the only way to fight against imperialism and to liberate Quebec. This should also have been combined with a call for solidarity with the Anglo-Canadian workers, who have a vested class interest in fighting against the oppression of Quebecers and in overthrowing capitalist domination and the bourgeois federal state.

In the absence of this, the prevailing confusion and lack of a class perspective gave the PQ space to grow, including on the left, which played a role in halting the rising radicalization of the Quebec labour movement. The FLQ was also characterized by this confusion.

The Vallières-Gagnon network

However, there was one short-lived group that approached a correct position. This group was the Mouvement de libération populaire (MLP), founded by Pierre Vallières and Charles Gagnon. Among the Felquists, Vallières and Gagnon were the closest you could get to theoreticians. They appeared on the scene in 1964 when they founded Révolution québécoise, a magazine claiming to be Marxist. This paper was unique in that it opposed the so-called “two-stage” position (first independence, then the socialist revolution) defended by the popular pro-independence socialist journal, Parti pris. Révolution québécoise rightly denounced the opportunism of Parti pris, given that its two-stage position pushed it to defend the possibility of alliances with the nationalist Quebec bourgeoisie. On the contrary, Révolution québécoise said, “Secession in itself is a measure to be fought if it is not necessitated by the establishment in Quebec of a socialist-type economy.”

Vallières and Gagnon took another step in the right direction in 1965 with the formation of the Mouvement de libération populaire. Created by the merger of Révolution québécoise and Parti pris, and joined by the Groupe d’action populaire and the Ligue socialiste ouvrière, a “Trotskyist” organization, the MLP aimed to form a party of revolutionary cadres, the “vanguard” of an eventual workers’ party. It recognized that “of all forms of struggle, the most appropriate for Quebec at the present time is open struggle,” and rejected armed and clandestine struggle for the moment. Pierre Vallières became its first full-time organizer.

At the same time, however, Vallières and Gagnon secretly maintained links with the FLQ, which they were considering joining. In October 1965, La Cognée published a text by Vallières (under a pseudonym) in which he criticized the movement’s amateurism and lack of seriousness: “The FLQ is, to all intents and purposes, a vague gathering of more or less active small groups of which (almost all) members are known to the police and to militant indépendantistes.” He adds, “In terms of action, they seem more often concerned with daily random acts, seizing any pretext to throw bombs and Molotov cocktails, as demonstrations or political events happen…”

In a turnaround quite typical of the ideological confusion prevailing at the time, Vallières and Gagnon quickly left the MLP and joined the FLQ, taking some of the MLP activists with them. Renouncing his position held a few months earlier, and criticizing the MLP, Vallières came to overtly guerrillaist positions in December 1965: “To want to create a vanguard party before the war of liberation is over is to put the cart before the horse… Here, as in Algeria and Cuba, the development of the Revolution towards socialism will not be the consequence of a precise doctrinal choice among the people and the fighters (activists and partisans), but the result of the very march of the Quebec people towards independence.”

The “Vallières-Gagnon network”, formed in 1966, became perhaps the most famous of the FLQ. While it was more oriented towards Marxism, it was a deformed Marxism, strongly influenced by Maoism. This influence reflected a general trend in the 1960s around the world, with the rise in popularity of Maoism and all its variants, notably Guevarism, through the colonial revolutions.

Colonial revolutions

The 1950s and 1960s were marked by a wave of national liberation movements around the world. In the year 1960 alone, 17 African countries gained independence. Cuban revolutionaries led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara took power in 1959. Algeria gained independence in 1962, after a violent war against the French occupiers led by the nationalists of the National Liberation Front (FLN).

The Felquistes considered themselves part of this anti-colonial movement. The first FLQ manifesto, published on 16 April 1963, begins as follows: “Since the Second World War, the various dominated peoples of the world have been breaking their chains in order to conquer the freedom to which they are entitled. After so many others, the people of Quebec have had enough of suffering the domination of colonialism.” The CLN, the precursor of the FLQ, gave its activists classes that “began with Algeria, Cuba, Vietnam, the French Resistance and the Patriots of 1837-1838.”

However, the anticolonial struggle often took the form of an armed struggle. Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party, at the head of huge peasant armies, had seized power in 1949 after a long guerrilla war against the bourgeois nationalist Chiang Kai-shek, allied with the Western imperialists, and against the Japanese invaders. Castro had overthrown the dictator Batista in a guerrilla war launched by a small group of revolutionaries armed with old rifles. The Vietnamese nationalists grouped around Ho Chi Minh kicked out the Japanese, then the French, and then aimed their guns at the American invaders. Che Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to continue guerrilla warfare in the rest of Latin America.

These victories gave enormous prestige to the methods of armed struggle and to the revolutionary leaders who used them, such as Mao and Guevara. Moreover, Maoist China succeeded, particularly in the colonial countries, in falsely presenting itself as an alternative, “revolutionary” model to the bureaucratically degenerated Soviet Union.

With these examples in mind, young people and workers eager to fight against national oppression and capitalism were forming armed groups all over the world: the IRA in Northern Ireland, ETA in the Spanish Basque Country, and even in the USA with the Weather Underground. Throughout Latin America, guerrilla groups formed, including the Tupamaros in Uruguay.

Quebec was no exception to the phenomenon. The FLQ established links with the Cuban and Algerian governments. Vallières and Gagnon went on a tour of the United States to meet with Black Panther activists. Two Felquist activists, “Selim” and “Salem”, received training in Jordan with the fedayeen, the Palestinian resistance fighters. On camera for Radio-Canada, they said, “We are going to orient our tactics towards selective assassination. The real perpetrators will pay. From a practical point of view, we would begin by killing the Prime Minister, but obviously that is not really possible.”

The ideology of the Felquists was therefore very much influenced by that of the anti-colonial movements. They read authors such as Frantz Fanon, Fidel Castro, Mao and Che Guevara. What they learned from all this was above all the emphasis placed on the armed struggle. In particular, Guevara’s strategy of “foquismo” (“focalism”) was reflected in the actions of the FLQ. This idea asserts that it is not necessary to wait to have the support of the masses before launching the armed struggle, but that a small group of revolutionaries can win the support of the masses by launching the armed struggle.

However, and without immediately going into the relevance or otherwise of the armed struggle as such, it is necessary to emphasize the particular character of the Cuban, Chinese and Vietnamese revolutions and how this explains the use of guerrilla warfare. In all three cases, guerrilla warfare was carried out by peasant armies against the weak state of a poor country or against foreign armies of occupation. But it would be ridiculous to believe that a small group of guerrillas could overthrow the might of a modern army of an advanced capitalist country on its own ground.

Moreover, these armies were fighting, among other things, for a program of agrarian reform in countries that were still largely rural and had an agriculture-based economy. They could therefore tap into a large, poor peasant population ready to wage a class struggle against the big landowners.

They were operating on guerrilla-friendly terrain, on the vast lands of China or in the jungles of Cuba and Vietnam. Guerrilla warfare is a peasant tactic typical of countries with little industrialization or urbanization, and which are highly agrarian. However, as we have seen, Quebec was 70 percent urbanized at that time, with a peasantry that had almost disappeared.

Ultimately, the weaknesses of Guevarist methods were tragically revealed in October 1967, when Che Guevara was captured and executed by the Bolivian army. The guerrillas around Guevara in Bolivia failed to gain the support of the peasantry. Moreover, U.S. imperialism had learned from its mistakes in Cuba. It had since refined its counterinsurgency methods and operations. The CIA had been sent to train the Bolivian army to capture and assassinate Guevara and nip the guerrillas in the bud.The same gangsters of the CIA later helped the Canadian government during the October crisis.

Armed agitation

Despite the grandiloquent statements about the approaching hour of insurrection, the FLQ never actually went as far as organizing guerrilla warfare. While there was constant talk of “training partisans,” of creating a revolutionary army, of “going underground,” the actions of the FLQ remained those of individual terrorism, “armed agitation”.

From 1963 to 1970, its activity was mainly concentrated on the planting of bombs (nearly 300 of them) and organizing robberies to finance itself. And the bombs would virtually never target human beings, generally exploding in empty buildings in the middle of the night. These attacks did result in 10 deaths, almost all accidental or not premeditated, including four Felquists. The most spectacular bombing was that of the Montreal Stock Exchange on February 13, 1969 in broad daylight, which left 20 people injured. All of this culminated in the events of October 1970, to which we will return later, after which the FLQ rapidly declined in 1971 and 1972.

In reality, armed agitation and the strategy of “foquismo” were nothing new at the time. It is essentially a reformulation of the old anarchist concept of “propaganda of the deed,” i.e., trying to encourage revolt by means of terrorist attacks. Charles Gagnon wrote, for example, on May 3, 1968, “The Quebec people are angry. All that is missing is the spark to ignite it. And it is precisely the role of the revolutionary vanguard, our role, to light that spark. It is necessary to set fire everywhere in Quebec. We must speak words of fire, perform acts of fire and multiply them.” It is rather ironic, moreover, that “Marxists” like Vallières and Gagnon defended these ideas, whereas the first Russian Marxists organized around Plekhanov and then Lenin had fought these very same ideas at the end of the 19th century.

Aside from the fact that it is illusory to think of leading a victorious guerrilla war in an advanced capitalist country, the ideas of individual terrorism and “urban guerilla warfare” are in fact foreign to Marxism. Marxism aims at a revolution in which the workers, representing the vast majority of the population, take control of the economy and democratically manage society. To achieve this, the workers have two great strengths – their numbers and their relation to the means of production; that is, the fact that they are the ones who operate industries, the means of transportation, the means of communication, etc. The methods of struggle defended by the Marxists are therefore those that are based on these forces: demonstrations, strikes, occupations. Guerrilla warfare, as we have seen, is a method of struggle based on another class, the peasantry.

But the methods of the FLQ were not really guerrilla warfare, but rather individual terrorism. Far from being an armed mass, the movement brought together a handful of individuals, a hundred at its peak. Speaking on behalf of the masses, it acted behind their backs and without their participation. Rather than relying on the strength of numbers, terrorism glorifies the individual action of small groups of “heroes”. Such an approach, far from pushing the masses into action, encourages their passivity. The methods of mass struggle give workers confidence in their own strength, lead them to participate in political life, and teach them important lessons about the nature of the state, the bosses and politicians of all kinds. Individual terrorism, on the other hand, turns workers into mere spectators and reinforces their feeling, desired by bourgeois democracy, that politics is something done by others.

In the best of cases, if a guerrilla group were to win and overthrow the capitalist state by such methods, it would not result in workers’ democracy, but would simply put the state machine back into the hands of the “elite” revolutionaries who led the struggle. The masses, not having participated in the revolution, not having learned to act on the political front during the revolution, would remain spectators once the guerrillas got into power. The workers would remain excluded from power. This is exactly what happened in a host of colonial revolutions, particularly in China and Cuba. While the abolition of capitalism and the overthrow of the rotten regimes that were in place before these revolutions represented enormous progress, China and Cuba remained regimes dominated by a bureaucratic caste removed from the conditions of the workers. In China, this group led the re-establishment of capitalism in the country, and transformed itself into a ruling class.

Underground work and democracy

Moreover, the emphasis on guerrilla warfare had pernicious consequences. Convinced that they were guerrillas, the Felquistes more or less abandoned open legal work and turned to underground work: “For the moment, it is a question of placing ourselves in the context of the popular struggle that is beginning its fight for power. This struggle will take the form of a guerrilla war, a war of partisans. This means that the struggle is already being waged and will have to continue to be waged in absolute secrecy, in the underground.”

The need to protect themselves from the police forced FLQ cells to seal off contact between themselves, and limited the possibilities of debate and discussion, which are conditions for a healthy democracy within an organization. This fetishism of underground work contributed to one of the FLQ’s major weaknesses, i.e. the lack of a real democracy in the organization. “One of the first qualities of the partisan will be discretion… It is a matter of not saying anything to anyone at any time – except to their immediate representative and their immediate collaborator(s) at the times scheduled for doing so.” This is what was asked of activists in L’Avant-garde, the paper of the cadres of the Vallières-Gagnon network.

Without a democratically decided political line between members, conflicts emerged. La Cognée, for example, denounced the “Marxist” turn adopted by Vallières and Gagnon: “No, the FLQ is not communist, contrary to the image that Vallières and Gagnon could have given to it temporarily… It is necessary to point out that there was no collaboration between us and the Vallières-Gagnon group.”

Thus, the political orientation and actions taken in the name of the movement could be decided by individuals or cells without consultation with others. The police took full advantage of this weakness. After the October crisis, undercover police officers created fake FLQ cells to issue communiqués for their own purposes. These fake cells were also used to push FLQ activists into carrying out attacks orchestrated by the police.

The armed struggle was the bread and butter of the FLQ, but also led to its downfall. It was its biggest feat, during the events of October 1970, that ended up destroying it.

October

We will not go into the details of the events of October 1970, which have been described elsewhere at length. The Liberation cell kidnapped the British trade commissioner James Richard Cross on October 5, 1970. It demanded, among other things, the circulation of a manifesto, the release of the “23 political prisoners” (i.e. their comrades in prison), the re-hiring of the “Lapalme boys” and $500,000. The company Lapalme was a sub-contractor of the Post Office from which the federal government had withdrawn its contract earlier in the year. The fierce struggle of the Lapalme boys to keep their jobs mobilized the left and the labour movement in 1970.

To buy time and give the impression that it was ready to negotiate, the government agreed to broadcast the FLQ manifesto. It was read on Radio-Canada on October 8: “Workers of Quebec, start today to take back what is yours; take what is yours… Make your own revolution in your neighbourhoods, in your workplaces.”

At the same time, the members of the Chénier cell (Francis Simard, Bernard Lortie and the Rose brothers, Jacques and Paul) were preparing to help the Liberation cell. On October 10, Quebec Justice Minister Jérôme Choquette announced that he refused to accede to the requests of the Liberation cell. Faced with this refusal, the Chénier cell kidnapped the Minister of “Unemployment and Assimilation of Quebecers”, Pierre Laporte.

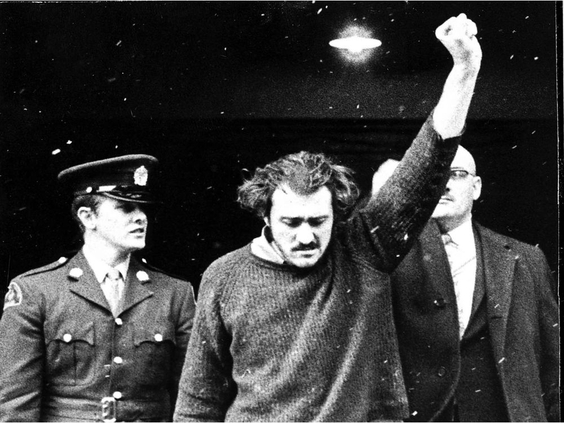

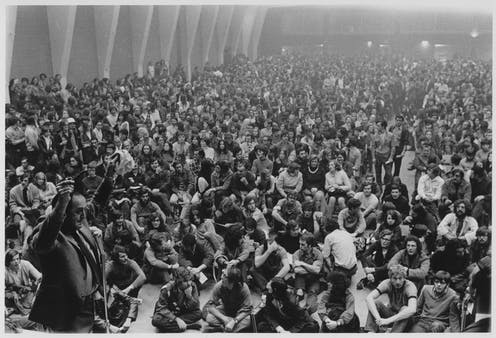

For a brief moment, the FLQ’s strategy seemed to be working. Charles Gagnon and Pierre Vallières toured student circles. On the 14th, Charles Gagnon addressed an assembly of students at UQAM and called for a strike. On the 15th, students from several CEGEPs and faculties at UQAM and UDEM went on strike to demand the release of political prisoners. In the evening, 3,000 people gathered at the Paul Sauvé Arena to hear Gagnon and Vallières, in addition to Michel Chartrand and lawyer Robert Lemieux, who was leading the negotiations with the government. The crowd chanted “FLQ! FLQ! FLQ!”

Repression

But the mobilization did not go much further. On the same day, under Prime Minister Trudeau’s pressure, the government broke off negotiations and began using repressive measures. The federal government put out the ridiculous propaganda that 3,000 Quebecois terrorists were preparing an “insurrection”. The Canadian army entered Quebec at 1:00 pm, with 8,000 soldiers concentrated in Montreal. Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s cabinet enforced the War Measures Act during the night. Civil liberties were suspended. The state gave itself the right to make arrests and perform searches without a warrant, as well as to keep people in unjustified detentions for up to 21 days. At dawn on October 16, the army and police launched a massive crackdown. They carried out approximately 36,000 raids and searches. Approximately 500 people were arrested or detained without being able to speak to anyone; 90 percent would be released without charge, and of the 10 percent who were charged, 95 percent would be acquitted or the proceedings were dropped.

In the eyes of many Quebecers, the October crisis revealed the real nature of the state. Minister Jean Marchand, Trudeau’s right-hand man, admitted 11 years later that using the War Measures Act was tantamount to “mobilizing a cannon to kill a fly”.

In the aftermath of the October crisis, repression increased. The forces of law and order would be much less reluctant to use scandalous methods. In November 1970, the RCMP submitted a report to Prime Minister Trudeau, explaining that in order to infiltrate the FLQ and “similar movements,” the RCMP would “have” to commit serious crimes in order to establish the credibility of its undercover agents.

From 1970 to 1972, fake FLQ cells led by undercover agents committed such attacks in full view of the police, such as the firebombing of Brink’s headquarters in Montreal on January 6, 1971. To recruit undercover agents and obtain information, the RCMP kidnapped, confined and threatened several people, going as far as to torture a young trainee working for the law office representing Felquist prisoners in 1972.

A December 10, 1970 report by the Strategic Operation Center, a secret federal intelligence group, pushed the federal government to go on the offensive against “separatism”. “Section G” was founded to carry out activities of “disruption”: infiltration and surveillance of independence groups. Perhaps the most heinous action on the part of the federal government as part of these activities was Operation Ham, a kind of Quebec Watergate, in which the RCMP stole confidential documents from the Parti Québécois, including its list of members.

Moreover, the role of American imperialism in the October events should be noted. An October 15 dispatch from United Press International states that “in FBI circles, there are fears of a fall offensive by groups such as the Black Panthers and the Weathermen.” Many CIA agents were sent to Montreal. “They were everywhere,” an RCMP officer later testified. It is suspected that Washington encouraged Ottawa to take the hard line, fearing that a successful FLQ would encourage the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground to take similar actions.

The death of Laporte

On Oct. 16th, Laporte cut himself on glass while trying to escape through a window and lost a lot of blood. He died the next day under nebulous circumstances that are the subject of many theories and debates. These are of little interest to us. In any case, the members of the Chénier cell took responsibility for his death. They were all eventually found and arrested within a few months. As for the Liberation cell, none of its demands were met, but it did manage to obtain safe passage to Cuba in exchange for Cross. The operation was a complete failure.

The events of October reveal above all the weakness of the FLQ, which was far from ready to lead a guerrilla war. From the first day of Cross’ kidnapping, the police more or less knew the identity of those responsible for it. All that remained was to find them. In fact, the members of the Chénier cell were already on the list of suspects in Cross’ kidnapping even before they kidnapped Laporte!

Despite all the attention the FLQ was receiving, the “armed agitation” of October did not push the masses into action. While there had been an initial mobilization among students on the 15th, the War Measures Act put an end to this. The students were agitated, but they ended up not doing anything. The strikes ended after a few days. Except for issuing some declarations, the unions remained essentially passive.

Jean-Marc Piotte, a former member of Parti pris and the MLP, made a very accurate analysis in his personal diary on October 22, 1970. Comparing October 1970 to the events of May 1968 in France, he writes,

In May, students, intellectuals and workers gradually mobilized against the bourgeois state. When repression fell upon them, they were ready to face it as they had been active during the offensive period.

Here, students and leftist circles were applauding a show put on by others than themselves, that is, by the FLQ. At this level, the beginning of the walkout showed sympathy for the Front, not an active movement against the state. Also when the state pulled out its repressive powers, the left-wing circles and students fell into complete panic, unable to react.

This difference between the French May and the period of the kidnappings marks precisely where the weakness of the Felquist strategy lies. Given the weakness of the current economic situation, the FLQ wants to fight for the workers, but it is absolutely unable to work with them to mobilize and organize them.

As we explained earlier, the methods of individual terrorism do not encourage workers to organize and mobilize, but make them mere spectators.

Moreover, the actions of the FLQ were directly harmful to the workers’ struggle. At the time, the momentum existed for the formation of a workers’ party independent of the Liberals, the Union Nationale and the nascent PQ. This mood was expressed notably through the formation of the Front d’action politique des salariés de Montréal (FRAP), a Montreal municipal party aimed at giving a voice to workers. The party was to run for its first election on… October 25, 1970. The October crisis dealt a severe blow to the FRAP. Jean Marchand claimed that the FRAP was a “front” for the FLQ, and Mayor Jean Drapeau made similar comments. Two of their candidates were even arrested under the War Measures Act.

One of the fundamental problems of individual terrorism is that it invites state repression without almost ever getting anything in return. In the most turbulent period in Quebec’s history, the kidnappings provided the pretext that Pierre Elliott Trudeau was looking for to settle the score with the left and with the indépendentistes. He did not care whether the arrests really had anything to do with the kidnappings. According to historian Louis Fournier, “the list of arrests included a certain number of ‘personalities’ but above all grassroots activists who were members of unions, popular groups, citizens’ committees, student movements, nationalist associations, as well as leftist political organizations (such as the FRAP) and the Parti Québécois.” The crisis benefited Trudeau, who saw his popularity temporarily increase both in Quebec and English Canada.

A week after the implementation of the War Measures Act, Jean Marchand had hinted at the government’s reasoning in an interview, saying, “It is not the individual action we are worried about now. It’s the vast organization supported by other bona fide organizations who are supporting, indirectly at least, the FLQ.” (Emphasis in the original) Then he continues, “Well, if it had been an isolated case of kidnappings, I don’t think we would have been justified in invoking the War Measures Act because there the Criminal Code would have been enough to try and get those men and punish them. But there is a whole organization and we have no instrument, no instrument to get those people and question them” (Our emphasis).

The repression was therefore not directed strictly against the FLQ, but against the entire national liberation movement and the left, this so-called “vast organization”. Polls and anecdotes from the time show that although the general population rejected the methods of the FLQ, a large part supported the spirit of the organization’s demands. It seems that, concerned about this “radicalization”, the Liberals wanted to nip it in the bud. Individual terrorism provided the ideal pretext to do so.

The experience of the FLQ and other terrorist movements in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrates quite clearly the adventurous and counterproductive nature of individual terrorism. But does this mean that revolutionary violence is to be absolutely rejected?

The question of armed struggle

For us, the question of the use of arms is not a question of principle. No one, except a few enlightened people living closer to the heavens than the earth, will deny that violence can be justified in certain situations. Few parents, no matter how pacifist they may be, would go so far as to say that they would let their child die rather than physically defend him or her.

Yet when the oppressed resort to force, there is an outcry and the immorality of violence becomes an absolute. The argument generally put forward is that we live in a democracy, therefore we have the means to debate and defend our ideas, therefore it is enough to go through democratic channels. Thus, René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois argued that the goals of the FLQ were justified, but its methods were not. Lévesque had described Laporte’s murderers as “inhuman beings”.

The problem with this view is that under capitalism, democracy exists only to the extent that it produces results that do not endanger the interests of the ruling class. As soon as democracy no longer suits the capitalists, any means become acceptable to crush their opponents, including violence.

Thus, US President Richard Nixon commented on the murder of Pierre Laporte, “This is an international evil, which lies in the following conception: if you have a cause to defend, you can use any means to achieve it, the end justifying the means… No cause justifies violence when the system provides for the right to change it peacefully.”

Obviously, Nixon meant that violence is never justified for the poor and oppressed, not for the ruling class. He did not hesitate to have the socialist president of Chile, Salvador Allende, assassinated three years later. When it was a question of preventing the Chilean poor and working class from expropriating the bourgeoisie and ousting US imperialism, the end justified the means.

The absolute rejection of force as a political tool to overthrow the status quo, when that status quo consists of violence by the oppressive class against the oppressed class, is tantamount to siding with the oppressors. As Chartrand said in response to the aforementioned stock exchange attack, “The terrorists did not create violence, violence created them. There are some among them who only defend themselves against the violence that has been imposed on them for generations. This violence is the violence of the capitalist system that forces workers to live in poverty, that drives them into insecurity and unemployment.” We, on the contrary, recognize that the oppressed have the right to defend themselves with all possible means. The violence used by the slave to break their chains cannot be equated with violence of the slavemaster to keep the slave in chains.

The entire history of revolutions, from the Paris Commune to the Chilean revolution, including the Russian, German and Spanish revolutions, shows that the capitalist class will cling to power with all the methods at their disposal, peaceful or not – even if it means shedding seas of blood. It is hard to believe that the ruling class would let itself be overthrown without doing anything. A socialist revolution will necessarily have to take steps to defend itself against the violent capitalist minority that will not want to let the working class take control of society. If we are not prepared to do this, we might as well give up now.

But this fact has led some to overestimate the power of arms, and to elevate armed struggle into a fetish. As an inverted reflection of the moralist view of violence, this position makes violence a principle for revolutionaries.

Just as a general would not use tanks to fight a naval battle or infantry to fight an air battle, we must recognize when a tool or method is not appropriate for a given context. As Marxists, the question of force is more tactical and strategic in nature. It is only one tool, one possible method of struggle. And like any method of struggle, it must be evaluated on the level of effectiveness, which depends on the context, the forces behind the revolutionaries and the tasks facing revolutionaries in that context.

The main task of revolutionaries is to assist the mobilization of the masses. Only the mass of the workers have the economic power to halt production, and the social power to overcome the violence of the capitalist state. In this context we are not talking about “violence” in the abstract, but the concrete defence of a mass workers’ movement that seeks to change society.

In the time of the FLQ, as today, the battle should have been fought on the political front. The first task of revolutionaries is to build the revolutionary organization. Once it is built, it must win the political support of the masses. The FLQ had never really undertaken this work.

Charles Gagnon later admitted, “Despite attempts to justify violent action (theoretically), the FLQ remained an essentially spontaneous movement, where direct, immediate action was mythologized to the detriment of political reflection, of strategic thinking articulated in terms of the prevailing social and cultural conditions.”

After October

The repression and demoralization that followed October practically destroyed the movement. Many Felquists were arrested. Others went into exile in Cuba, Algeria or France. The FLQ continued to commit attacks here and there for several years, but without the same vigor.

Another blow was struck when Charles Gagnon and Pierre Vallières left the FLQ towards the end of 1971. While Gagnon turned more seriously toward Marxism, Vallières went to the right. Abandoning the ultra-leftist posture of individual terrorism, he adopted an opportunistic position of support for the PQ. He maintained that “in a colonized society, the question of independence is not just one question among others for workers, but the most important question.” He returned to a stagist position: independence was “the first condition for the construction of socialism.”

In fact, ultra-leftism and opportunism often represent two sides of the same coin: impatience. Impatient to achieve revolution as quickly as possible, the Felquistes had tried the shortcut of bombs. Having burned their fingers (sometimes literally) with terrorism, Vallières now capitulated to the PQ. This represented a retreat from the position of class independence that had been previously defended by Vallières and Gagnon.

The Felquistes paid dearly for this impatience when they missed the boat during the 1972 Common Front strike.

The 1972 Common Front

In reality, while the bombs of the FLQ were impressive, the FLQ’s action had remained marginal compared to the process of radicalization of workers’ struggles that had begun in the mid-1960s.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, there had been a resurgence of class struggle in Quebec. The post-war boom had begun to slow down. The economy had deteriorated, and the Quiet Revolution had run out of steam. Strikes had become more frequent, long, and combative. Major conflicts had broken out. The Dominion Textile strike of 1966 lasted five months and mobilized 5,000 workers. The “Cabano revolt” a few months before the October crisis, saw the small village of Cabano rise up to protest job losses. Almost exactly one year before the October crisis, the particularly combative Taxi Liberation Movement took advantage of a strike by firefighters and police officers to ransack a Murray Hill garage. As a harbinger of the events of the following year, the army was deployed.

It was increasingly apparent that the Quiet Revolution had served the Francophone bourgeoisie above all. The Francophone bourgeoisie was beginning to do well for itself in the mid-1960s. It began to consider the creation of a Quebec employers’ association to defend its own interests. In 1969, it had founded the Conseil du patronat du Québec, because of “the need for companies to define a common point of view in the face of the militancy of the labor movement and the various common fronts,” according to one boss at the time.

Class divisions were opening up within the Quiet Revolution. We have already explained this process:

The Liberal government of the early 1960s had created a space for the development of a genuine national bourgeoisie. While there were now Francophone capitalists who had found their place in the sun, the working class had not benefited nearly as much from the Liberal reforms, and their living conditions were still very difficult. Wages were still low and unemployment, which had dropped from 9.2% to 4.7% between 1960 and 1966, grew from 5.4% to 8.3% between 1967 and 1972. As the crisis developed, it was becoming clearer and clearer that the petty bourgeois elements in the Liberal Party and the rising Quebecois bourgeoisie had a very different understanding of the Quiet Revolution than the workers. While the Liberals and their allies basically wanted to create a modern capitalist state and give concessions to the workers to buy class peace and avoid the class struggle which marked the Duplessis era, the workers were more and more seeking to move beyond the capitalist system.

Quebec was ripe for a massive confrontation between the workers and the bourgeoisie – Anglophone and Francophone alike. This process culminated in the spring of 1972. We will not go into the details of an event about which we have already written, but it is worth emphasizing its scope and its radical nature.

Towards the end of 1971, the unions were already on a revolutionary path. The CSN published its manifesto Ne comptons que sur nos propres moyens (known as “It is up to us” in English) in October 1971. In it, the CSN took a stand for socialism and denounced imperialism and capitalism. A few weeks later, the locked-out workers of La Presse suffered harsh repression, and the Montreal police claimed a victim, when Michèle Gauthierx suffocated to death when police fired tear gas into the crowd. The three major unions (along with the FTQ and the Corporation des enseignants du Québec, the forerunner of the CSQ) got together and decided to join forces. Louis Laberge, president of the FTQ, speaking of Michèle Gauthier, stated that “in the future victims will not be just on our side.”

Collective bargaining in the public sector began that spring. A massive general strike was called. The Quebec state decided to take a hard line and crack down on the movement. The leaders of the unions were imprisoned. But the strikers did not back down, and other sectors of the working class were swept into the struggle. At its peak, more than 300,000 workers had walked off the job. The state practically lost control of some cities, such as Sept-Îles. The question of power began to arise. The crisis reached revolutionary proportions.

In the end, however, the union leaders backed down and negotiated an end to the strike. While the workers made significant gains, the ruling class remained in power.

Where were the FLQ revolutionaries then? When the Quebec working class finally rose up and led Quebec into a near-revolutionary situation, the Felquistes languished in prison, in exile, or in demoralization.

This is an important lesson for today’s revolutionaries. The Felquistes had every reason to be impatient. Francophone workers in Quebec had suffered in humiliation for too long. But, in their haste to make revolution, the FLQ spent the 1960s trying in vain to artificially excite the workers with bombs, rather than preparing for the moment when the working class would actually rise up.

Today, with a planet that is dying in front of our very eyes and a ruling class that uses the novel 1984 and the Black Mirror series as instructional guides, it might be tempting to succumb to the same impatience. Yet it is precisely because the stakes are so high that we must keep a cool head. We must prepare now for the next “May ’68” or the next “1972 Common Front”.

How to lead a victorious revolution?

The somewhat ironic truth is that it is not revolutionaries that make revolutions. In order to overthrow capitalism, the ruling, capitalist class must be overthrown. Revolution is struggle that pits class against class. Leon Trotsky once said something rather profound when he wrote, “The most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events.” The workers, normally excluded from the important decisions that affect their lives, suddenly take a mass interest and intervene in politics, and in the economy.

The fact that millions of workers suddenly decide to break with routine and transform society cannot be explained by the activity of a handful of revolutionaries. Rather, it is a particular historical phenomenon in which all the contradictions of capitalism lead to a deep crisis of society. All the accumulated anger of the workers erupts, and they suddenly seek a solution to their problems. Overnight, the overthrow of all the institutions in place no longer seems such a crazy solution.

However, in order for this process to end with a socialist revolution, that is, not only the overthrow of the ruling caste, but the profound transformation of the economy and society in general, a revolutionary movement of the masses is not enough. This fact has been abundantly demonstrated since the economic crisis of 2008, with the innumerable mass movements that have led to a change in the ruling party, or unsatisfactory reforms, without really improving the living conditions of the masses of poor and working people. One need only consider the Arab revolutions of 2011 (Tunisia, Libya, Egypt) and the movements of recent years (Chile, Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan, Ecuador, etc.).

It is precisely the task of revolutionaries to show the movement the way forward to the socialist transformation of the economy. Every mass movement has a leadership, however spontaneous it may be. If the socialists are not prepared to provide revolutionary leadership of the movement, it is the reformist parties or union leaders who will take the lead.

The building of an organization capable of giving this direction to a workers’ uprising requires long-term work. Lenin spent almost 20 years building the Bolshevik Party. “A well-organized revolution requires one or two years of preparation,” the newspaper La Cognée asserted. And La Cognée represented the “patient” wing of the movement!

In order to build the party of hundreds of thousands of workers that took power in October 1917 in Russia, the Bolsheviks first had to spend decades building the structure of the revolutionary party. This involved recruiting individual revolutionaries and turning them into professional revolutionaries, leaders with years of experience in the workers’ struggle.

In fact, more than in the handling of weapons, these revolutionaries were mostly trained in the handling of ideas. In order to know how to navigate through a revolution, one must study the history of past revolutions and the history of the class struggle, study the workings of capitalism, its economy and political structure, and so on. In this sense, Marxist theory should not be seen as something of mere scholastic interest, but as an indispensable weapon in the hands of revolutionaries.

Charles Gagnon ended up recognizing this, and devoted himself to building a Marxist organization, En lutte! (“In Struggle!”), which addressed more seriously the question of the creation of a revolutionary workers’ party (the reasons for the rise and fall of En lutte! are beyond the scope of this article). But the 1980s and 1990s were a period of reaction and demoralization throughout the world, with the return of economic crises and the dismantling of the Soviet Union. The revolutionary ferment of the 1960s and 1970s almost died out, and the question of sovereignty or federalism came to dominate Quebec politics to the detriment of the class question. The opportunity that had presented itself with the 1972 Common Front had been missed. But since the economic crisis of 2008, the class struggle has returned to the fore, pushing the independence debate into the background. With the deep crisis of capitalism in which we find ourselves, it is urgent to prepare for the important struggles that inevitably await us. The best way to honor the memory of revolutionaries like Charles Gagnon and Pierre Vallières is to learn from their mistakes, so that the next time we will be victorious.